South African photographer Pieter Hugo shot the colorful photos in California Wildflowers (through November 9 at Jonathan Carver Moore Gallery, SF) 10 years ago, when he came to San Francisco from Cape Town for a residency at the Headlands Center for the Arts. Hugo, whose work include The Hyena and Other Men, Nollywood, and Rwanda 2004: Vestiges of a Genocide, ending up spending his days in the Tenderloin, taking photos of people he met there.

The photos, which haven’t been shown before, now hang in the neighborhood where they were made. In the gallery’s words, “In his many days of visiting the area he met people from all walks of life and who faced many different challenges—be it victims of the 2008 recession, war veterans, or people experiencing mental health problems, but most importantly he found a sense of community that exists in the Tenderloin. Notwithstanding their circumstances, which are real and inescapable, Hugo found that there is something quite ecstatic in the poses and gestures of the people he photographed.”

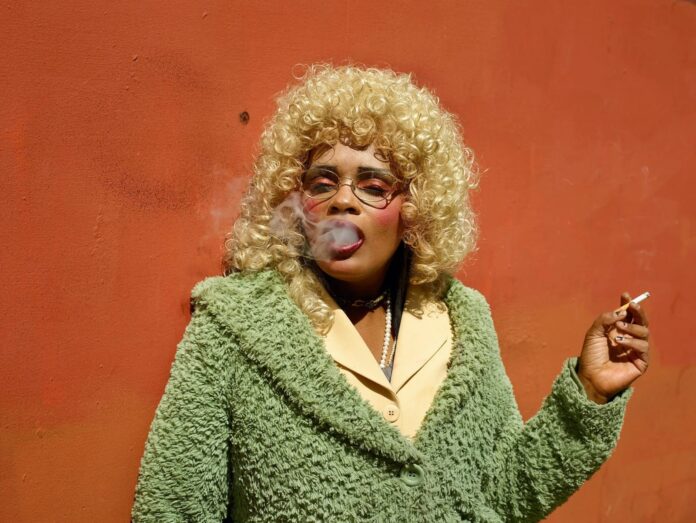

Hugo, whose work has shown everywhere from the Centre Pompidou to SFMOMA, started taking photos when his father gave him a camera for his 12th birthday. He felt it enabled him to look at the world critically. At the gallery, surrounded by his photos of a man holding his dog as it licks his face, a woman blowing out a cloud of cigarette smoke at the camera, and someone posing with their popsicle, he talked about what drew him to take photos in the Tenderloin, why he wanted to show the work with Moore, and how taking these photo shifted his practice.

48 HILLS How did you decide to photograph people in the Tenderloin?

PIETER HUGO I came here on a residency at the Marin Headlands. In fact, it’s the only residency I’ve ever done. I came with my partner and our two children. My son was one, and my daughter was four, and we got her into a school in City Hall. There’s a school in the basement.

I had a studio space, and I actually wanted to take a break from practicing photography. I needed to sort out my archive, and I just wanted some space to do it. My partner brought our daughter to school her first day, and then she went for a walk around this neighborhood. She phoned me and she said, “You got to come down here. This is right up your alley.” She knows my sensibilities.

I went from not going to make work to shooting every day. For three months, I’d go through a ritual of bringing my daughter to school, shoot throughout the day, and then I’d drive back to the Headlands. It was this incredibly strange juxtaposition. I just kind of aimlessly wandered around this neighborhood for months, and then we rented an Airbnb for a couple of weeks, and then when photographer Jim Goldberg was away I stayed in his apartment for a month or so.

48 HILLS Are you glad you skipped going through your archives to do this?

PIETER HUGO I’m very glad. Super glad. It actually created a shift in my practice after making this body of work. I’d always worked in a very formal way, and with this I was forced to work a bit faster and looser. That’s one thing that had happened. I kind of finally trusted myself, my ability to be able to work looser. Like in that picture, [one of a man in front of a tiled wall], the composition where the line goes, it’s not perfectly symmetrical. See how the lines on the left go up. I would never allowed myself something like that before. Things like that. And I had always shot at eye level. I had all these kinds of restrictions that I wanted to get rid.

48 HILLS Besides the aesthetic possibilities, what else drew you here? Do you see similarities at all between Cape Town and this area?

PIETER HUGO Honestly, I just want to say that I don’t know enough about regional US politics to have a qualified opinion about the Tenderloin and the community here. I’m not coming at it from that angle, right? What drew me to this was a visual attraction, primarily—the pathos and confrontation and posturing and playfulness. But one can’t separate it from the environment in which it’s made, right? One of the things that gives photography its energy is also what makes it problematic, which is that it’s voyeuristic. Inherently, it’s about the act of looking.

In Cape Town, there’s a massive homeless community, particularly after COVID. Here, it’s quite contained to certain neighborhoods, but in Cape Town, at every traffic light there’s someone panhandling. It’s just ubiquitous. There are constant conversations about how does one deal with this? How does one manage this? What are one’s obligations and responsibilities? Some people see there’s a Darwinian struggle, and that these are just freeloaders made bad life decisions. And some people have a more sympathetic view.

48 HILLS You have said you’re not interested in moral judgment. How does moral judgement come through in photography?

PIETER HUGO When I started my career as a photographer, I initially worked as a photojournalist and then from that, I started working for organizations like the World Health Organization or the UNHCR [the UN Refugee Agency], things like that. I would sometimes get assignments like, “OK, go to Rwanda, find a woman who was raped during the genocide, fell pregnant, contracted AIDS, has a child born out of rape, is now receiving antiretrovirals because of the World Health Organization, and is leading a happy life.” I just felt like a propaganda agent illustrating other people’s agendas.

But at the same time, I am drawn to the world around me. I’m not a studio-based practitioner. I’m on the street in the field. That element of it I’m still very attracted to and resonates with me.

48 HILLS I read that you said the people you took photos of in seemed happy to be photographed.

PIETER HUGO I think a big part of being homeless is being bored. There’s not much to do, and you can’t afford to do anything, like there’s nothing is free. You can see, like this woman, this was very performative [points to the person holding up their popsicle and leaning back]. And like, this guy [the one holding his dog], he posed like this for me. It was a combination of collaborative image making, and then some stuff that’s observational.

48 HILLS You did this work about 10 years ago, and you haven’t shown it. Why did you want to show it here?

PIETER HUGO I did show some of the work on a mid-career retrospective. But other than that, I haven’t shown the work. I’d already decided when I made the work, this is going to be more interesting if it has a bit of time to be separated from the immediate politics of that time. Photography, I think, is one of the few mediums, that time is actually good to. Also, I’m aware of the power dynamic between myself and the subjects that I photographed. And so, showing with Jonathan, who’s in the Tenderloin and is a person of color, it was like, “OK, this is where it should be. This is where it should be seen.”

CALIFORNIA WILDFLOWERS through November 9 at Jonathan Carver Moore Gallery, SF. More info here.