Aided by a USC fellowship, reporter Tom Molanphy and 48hills dug into the overwhelming history of data concerning the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, which has been in clean-up mode since being declared a Superfund site in 1989. With expert guidance from a 2022 Civil Grand Jury Report and a shallow groundwater response to sea-level rise study, the numbers add up to one irrefutable takeaway: the devastating impact of displacement on one of the city’s most vibrant communities. Read part one here.

II. After the Base (1974-1999)

Despite the work of Ruth Williams and other activists to maintain an economic engine within Hunters Point, the Navy closed the Shipyard in 1974. After being pushed out of the Fillmore by Redevelopment, many African Americans who had fled the Jim Crow South for a slice of the American Dream found themselves not only without a home but without a job. And San Francisco in the 1970s was not a very hospitable place to begin with.

As detailed in David Talbot’s book Season of the Witch, the national turbulence of that decade—Watergate, Vietnam, inflation—was the backdrop to the local horrors the city endured—the Zodiac killer, the assassinations of Harvey Milk and Mayor Moscone, and the insanity of Jim Jones, who preyed on the same people who had been disenfranchised by Redevelopment.

Meanwhile, the Shipyard needed repurposing. Finding a second use for a nearly thousand-acre decommissioned Shipyard site is like repurposing a mall—if oils, chemicals, solvents and radioactive material had been stored and spilled in the mall for 40 years. Triple A Manufacturing took over a portion of the site from 1975 to 1985 but was fined for multiple environmental infractions. A hodgepodge of business ventures, including a mushroom farmer, tried to make use of the decommissioned military site.

For many unemployed African Americans in Hunters Point, the economic fallout from the closure symbolized promises broken ever since “40 acres and a mule.”

“They say we’re going to have jobs out there for years, work out there, cleaning it up,” Hunters Point resident Jessie Banks recalled in 1995. “But when it came to hiring they said, ‘No, they can’t work out here because they’re not trained, it will kill them.’ So that meant Black people didn’t have anything to do. So [the companies] brought in people from everywhere else but Hunters Point.”

Since its closure, only one group has had steady success in repurposing the Shipyard. And like many transitional moments in San Francisco history, it took a group of artists to push past a dead end.

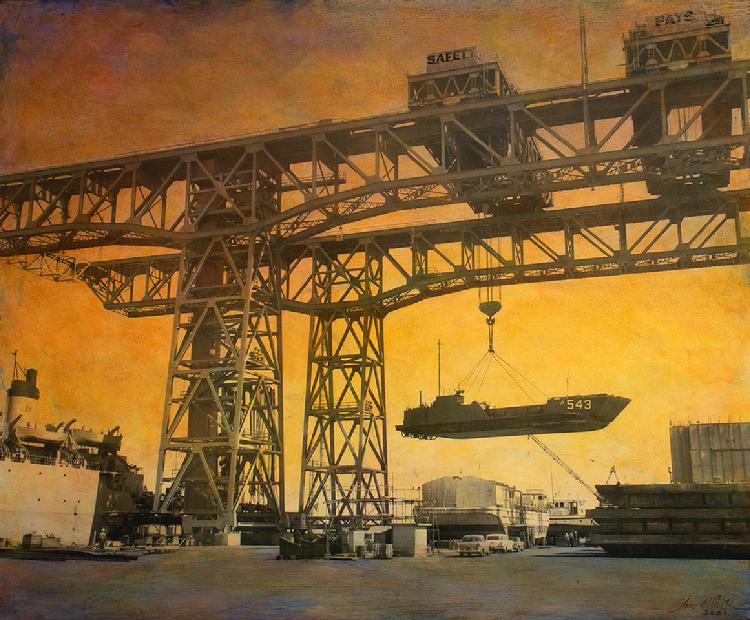

Stacey Carter pushes a blonde strand away from her eyes as she leans over a table full of photos. While photographer David Johnson’s mid 20th century work fed off the intimacy of the Fillmore and Bayview, Carter’s work gorges on the massive scale of the Shipyard. Her 2022 ink pigment and acrylic work on her wall pays homage to the dominant structure of the Shipyard, the 1,000 foot tall gantry crane that popped the turrets off battleships like bottlecaps.

“I’m always trying to show how monumental things are,” Carter says. “Big everything.”

Carter’s neatly organized Studio 1111 in Building 101 is part of the Shipyard Artists, to-date the most successful use of the former industrial site. When Triple A began subletting buildings to civilians in 1976, Jacques Terzian, a found-object fabricator, saw the potential. The emptied barracks “had so many damn windows, and that’s what artists want. They want that northern light.”

As soon after Carter moved into her Parcel B studio in 1998, she became more and more interested in preserving the Shipyard history. She eventually got a hold of the historic context statement from the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency.

“I stayed up all night reading it and was like, Oh, my God, this place is so significant. It played a role in events that turned the tide of global history.”

Carter had scratched the surface on the staggering amount of records on the Shipyard, where two-page Department of Public Health memos lead to hundred-page EPA responses to be followed up by thousands of pages of Navy retorts.

“A fundamental challenge posed by the Shipyard is that the process which governs the cleanup is arcane and very difficult to understand,” the 2022 Civil Grand Jury Report stated. “Dozens of documents are generated every year, all written in dense technical jargon, and overwhelming for the uninitiated to navigate or even locate. For most of the city, the cleanup process is inaccessible, even invisible.”

But if you’re an artist, accessing the invisible is just another day at the office. The maddening puzzle of local, state, and federal regulations can act like catnip to someone with Carter’s curiosity. For example, an 87-page 1984 assessment of the site by the Naval Energy and Environmental Support Activity revealed what had been transported, tested, burned and dumped in the Shipyard – most prior to any type of EPA regulation.

“Car mechanics have small containers full of solvent to clean off parts,” Carter says. “Well, here they’re working on aircraft carriers, so they had swimming pools of solvent.”

As grand as the ships look in the photos, the records revealed what kind of industrial waste was generated to build and repair them. From 1958-1974, 20 acres of the west shore of the Bay was filled up with an estimated million cubic yards of solid waste; 21,000 gallons of liquid chemical waste; 500 cubic yards of asbestos; and 6000 pounds of fluorescent radium dials and knobs from ships.

The most notorious use of the Shipyard is documented by one dramatic photo that’s not on Carter’s wall: a ballooning water cloud in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, so enormous that the Navy destroyers surrounding the blast resemble bathtub toys. In July of 1946, “Operations Crossroads” discharged two nuclear bombs, one overhead and one underwater, near 240 Navy ships to see, well, what would be left.

According to The San Francisco Chronicle, “The results startled US officials. They had expected some contamination but not the near-total poisoning they observed among the assembled cruisers, battleships and aircraft carriers. Operation Crossroads turned them into ‘radioactive stoves’ that ‘would have burned all living things aboard with invisible and painless but deadly radiation,’ officials wrote in a secret cable to the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington.”

Seventy-nine of the damaged ships were hauled back to Hunters Point Shipyard, where workers sandblasted surfaces to remove radioactive material. Gilly Jenkins, who took part in cleaning one of the most damaged ships, told NBC Bay Area News the ship was “Hotter than a pistol. It would melt a Geiger counter.”

Despite the harrowing history and widespread contamination, Carter is convinced that most of the Shipyard can be cleaned up.

“I personally believe it can be done. With all the money that they’re sinking into this place and all the money that’s to be made from it. They could pull this off.”

As Carter’s amazement of the history of the Shipyard grew, her appreciation for the vision of the Shipyard shrank.

“If Lennar (the developer) had their way, they would raze every building and replace it with vertical housing everywhere. Florida suburban faux-Tuscan villages of dirty pink stucco. There would be no soul to this place. It would be a damn shame if that happened.”

“That’s what kills me.”

She thinks a mix of old and new construction would benefit the whole community, a diverse locale with art and culture that sounds like the Fillmore that David Johnson roamed through in the 1950s.

Just as Johnson and Williams blasted Redevelopment for putting profits over people, Carter sees greed as the driver for such poor long-term planning for the Shipyard.

“It’s all about money. That’s the bottom line. For years it was the three-ring circus. You’d see something out here that wasn’t quite right. The city would point to the developer and then the developer would point to the Navy, and it would just go round and round and nobody would answer anything.”

Once Carter started attending Hunters Point Citizen Advisory Committee meetings, her admiration grew for the work of Ruth Williams and the “Big Five,” work that has been carried on by activist-heirs such as Marie Harrison and daughter Arieann Harrison.

“The artists and the activists are the only constant out here. Strongest people, I think, in this whole thing are the Black women activists. They don’t take any BS, you know?”

She made a personal promise to Dorris Vincent, a longtime defender of Hunters Point. “I remember Doris telling me, ‘They’re just waiting for us all to die. So that everybody will forget what happened here.’ And I looked at her and said, ‘Don’t worry. I won’t let them forget.’ And she said, ‘Good.’”

When the specter of City Hall politics is raised, the kind of machinations that Kevin Williams battled and that could prevent the recommendations of the Civil Grand Jury Report, Carter is as suspicious as anyone.

“I come from New Jersey and Atlantic City. My mother worked in the government of New Jersey, honey, Atlantic City. I tell you, this place is worse. Which is shocking.”

When asked about the specific warnings of the Civil Grand Jury Report, Carter believes what she has seen with her own eyes.

“I jumped the fence out here, years ago. It was freezing cold, and there was a storm. And I watched wave after wave crash over that drydock wall. And we’re talking about how much sea level rise? So, yes, it’s going to be a big problem.” (The neighboring Islais Creek studios saw flooding in January.)

(Adding a rock barrier, or revetment, and a 3-foot high wall are some of the measures the Navy has undertaken to address sea-level rise from climate change. The 2022 Civil Grand Jury report contends that “conventional defenses against sea level rise, such as sea walls, offer no protection from flooding from below, and can even exacerbate flooding by creating a barrier that keeps risen groundwater from flowing out.”)

“I’ve never been okay with just the cap. You can’t do that and have people living and working here. I’m not a scientist, but I think that there’s certain parts of the Shipyard that should never be built on.”

“Just don’t do it. Why put people at risk?”

***

While the Shipyard Artists were able to cut out a piece of the Shipyard for studios, the surrounding neighborhood languished. As dark as the 1970s had been for communities of color in San Francisco, the 1980s unleashed the War on Drugs, a vehement campaign that decimated entire neighborhoods. In Hunters Point, thousands of young men were locked up, creating the prison pipeline system that fostered gang violence in San Francisco through the 1990s.

Alicia Garza, co-founder of Black Lives Matter, learned how to organize on the streets of Hunters Point and saw the toll of the War on Drugs firsthand.

“Drug use became synonymous with Black communities, even though our communities use drugs at roughly the same rate as white communities,” Garza wrote in The Purpose of Power. “For an impoverished Black America, the War on Drugs was a war on Black communities and Black families.”

The state of the Shipyard also went from bad to worse, as the EPA declared it a Superfund site in 1989 for the staggering amount of toxins found there.

In 1991, a couple migrated from Alaska for the same reason David Johnson had decades before: work. When they felt employment was being denied due to race, they bought a newspaper to fight for the rights of all Hunters Point citizens. And that fight become inextricably linked to the clean-up of the Hunters Point Shipyard.

***

At the mention of David Johnson, Mary Ratcliff’s stern face breaks open with joy. The former editor of the San Francisco Bay View can’t remember the name of the young African American photographer she employed back in 1992. But she clearly remembers David Johnson’s influence.

“It was a beautiful interaction between this very young photographer and this much older man who had so much history and just a zillion photographs. That’s how I learned about the Fillmore and the Harlem of the West. I learned it from David Johnson.”

Ratcliff sits at her dining room table, just a swivel away from her office desk in her Bayview apartment on the corner of Third Street and Palou. It’s not unusual for an interview with Mary Ratcliff to be interruptedby a collect phone call from a prison; like her friend Alicia Garza, she connects the dots between unemployment in Hunters Point, the War on Drugs, and the catastrophic spike in incarceration rates. Even the devastation wrought by Redevelopment in the Fillmore haunts Ratcliff to this day.

“This city has an economy based on tourism. And the Fillmore was an incredible tourist draw. I mean, that takes anti-Blackness to a real extreme.”

Stacked against the walls of her living room are bundles of San Francisco Bay View newspapers, the morgue going back decades. Flipping through the yellowed pages, you enter another world.

To Ratcliff’s mind, Hunters Point has always been treated as separate and not equal to the rest of San Francisco. So it’s little wonder that she is not just aware of the 2022 Civil Grand Jury Report, but also the largely ignored 2001 and 2010 reports, as well.

“Oh, we’ve worried about sea level rise and contamination (at the Shipyard) for decades. But what’s significant about this Civil Grand Jury Report is that people are paying attention to it.”

Reading all three reports offers not just a timeline of the clean-up but a rising fear of its overall effectiveness. In hindsight, the slim 2001 report appears almost doe-eyed in its optimism, lauding the passage of Prop P as “official City policy for the environmental remediation of HPS, and calling for the prompt and thorough clean-up of the Shipyard.” The 2010 report, “Hunters Point: A Shifting Landscape,” is more wary, disputing an SFDPH official claim about the site that “there is no evidence that the really bad stuff is here. It’s in the Farallones.” Twelve years and one major falsification scandal later, the 2022 Grand Jury report reads either as adult, alarmist, informed or all of the above.

“Even back in the 1990s, we were convinced that sea rise was real,” Ratcliff says. “Talking to the Navy about it, you’d think that they had never heard of it.”

Ratcliff credits the toxic fire that burned for months in Parcel E2 in 2000 for shedding a sickly light on the situation.

“We knew about the methane under the ground in Parcel E-2. And they couldn’t put that fire out.”

The San Francisco Bay View put the fire front and center of its coverage for months. The pressure resulted in a community meeting with the EPA in the early 1990’s about Parcel E-2 that Ratcliff will never forget.

“I was sitting over there,” Ratcliff says, pointing to a wall, imagining the scene. “Big EPA guy was sitting over here. People stood up and talked about their fears. Very intelligent testimony. Ordinary people, well-versed.”

What Ratcliff remembers most was the EPA rep’s response to the demand that the toxic soil of Parcel E-2 be dug up and moved, once and for all.

“He says, ‘It’s too dangerous to move.’ Too dangerous! And when we said, ‘Then isn’t it too dangerous to leave it there? Or to build on it?’ And he just looked down at his feet.”

“They spelled out our doom right there. So I don’t think we have a choice. We have got to stop them.”

When asked what could be done with the land if it was cleaned to the Prop P standards, Ratcliff recounts a vision as grand as Johnson’s Fillmore or Carter’s repurposed Shipyard. Before the extent of the contamination was understood, the SF Planning Department divvied the Shipyard into residential and commercial lots.

“We were all invited to choose a lot. And Willie and I chose this gorgeous lot with this beautiful art deco warehouse completed in the Depression, during WPA projects. Beautiful. Three stories. We were going to put the printing press on the ground floor, offices for the paper and the construction company above, and then we would live on the top floor. And we were right on the water. They were going to build a ferry slip right outside.

“Oh my God. Can you imagine?”

Ratcliff’s dream didn’t stop at the doorstep of her art deco office/home.

“Willie and I had this wonderful vision of the Shipyard as a part to the city, a place where the housing was all affordable. A place where there was lots of creativity — the artists are already there. There could be parks, not unlike Golden Gate Park. Businesses owned by the people who lived here.”

After a few sumptuous moments, Ratcliff shakes herself from this dream. San Francisco Bay Viewreporters heatedly brainstorm pitches in her living room. A stern poster of Frederick Douglass on the kitchen wallwarns if there is no struggle, there is no progress. Her husband, legendary Bay View publisher Willie Ratcliff, shuffles across the adjoining bedroom, beaten down from years of lost contracts and broken promises. (“The most universal characteristic of the life of a Black contractor is not being paid,” Mary Ratcliff explains. “You’re always having to chase your money.”)

There is much to be despondent about. But Ratcliff ends her dream of the Shipyard with the steely-determination that makes her a pragmatic editor and resolute cancer survivor.

“And if it can’t be cleaned? Stay the hell out.”

Part III next week: The land transfer of the Shipyard from Navy to the City begins.