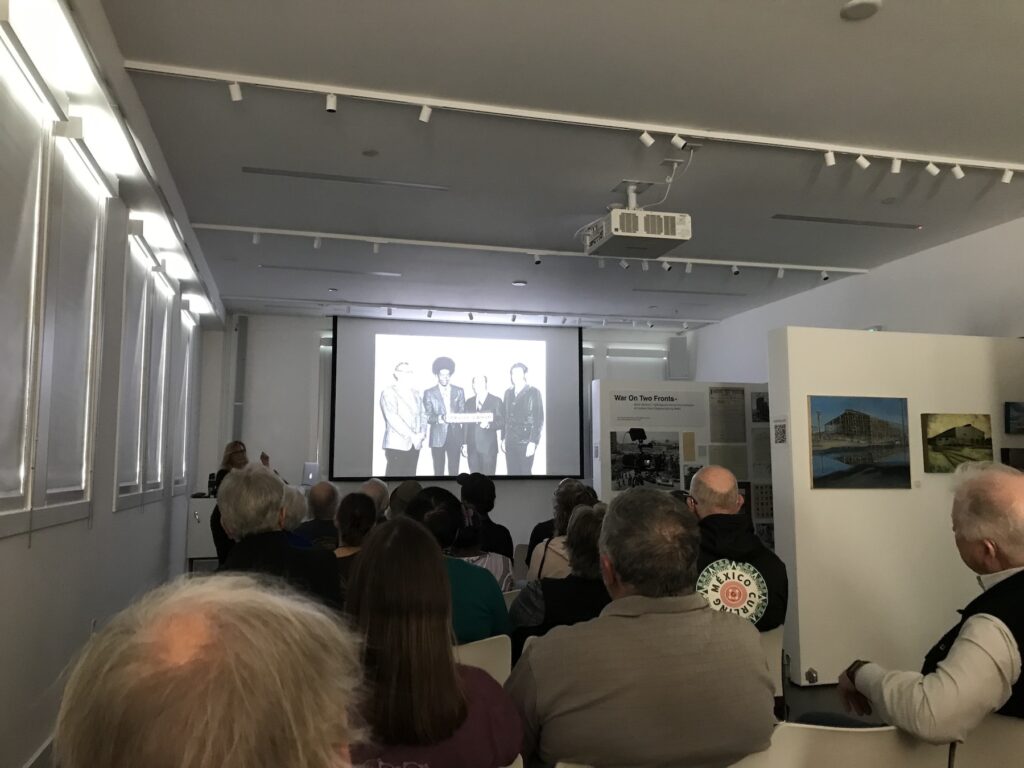

In an illustrated talk on Feb. 25 called War on Two Fronts: Black Workers Fight Against Racial Discrimination at Hunters Point Shipyard During WWII, Shipyard artist and historian Stacey Carter melded art and research to touch the heart and challenge the mind.

“Let’s get started,” Stacey Carter said, calling the 40 or so attendees of her presentation to attention. “We have a lot to go through.”

Carter’s two-hour slideshow and Q&A in Room 1212 of Building 101 of the Hunters Point Shipyard Artists complex last Saturday was just that—a lot. But it had to be. No other 900 acres of San Francisco, first fabricated out of a mountain top in the city’s southeast to berth battle ships for WWII, has been so argued and analyzed as the shipyard.

Carter shared the written and visual spoils of her countless hours of research, including deep dives into the National Archives in San Bruno. The origin story of the current shipyard, as fantastic as those from any Marvel movie, drew audible gasps from the crowd.

Aerial photos of the Navy’s massive expansion of the shipyard after Pearl Harbor revealed a stunning before and after as stark as the Bay before and after the Golden Gate Bridge. Where once rose the tawny brown of a California mountain, Pt. Avisedaro, in one shot, now sat a Navy shipyard, spread into the bay on the mountain’s rubble, in the next.

As dramatic as the physical change was to the landscape, the societal change, and the main point of Carter’s presentation, was even more dramatic. The domestic labor shortage created by the war abroad created “unprecedented job opportunities,” a major catalyst for the Great Migration that changed the country in ways still felt today.

By 1945, the Navy had not only built the largest drydock in the world to repair ships, but had created housing on a scale that 2024 San Francisco could only dream of: 12,000 housing units for 26,000 workers. The Black population of San Francisco leapt from 5,000 to 32,000 from 1940-45.

African Americans workers “came here not just for a better job but a better life,” Carter said. “But Jim Crow followed the workers here.”

Despite Executive Order 8802 in 1941 by FDR, racist strategies prevented equal opportunity for African American workers at the shipyard. Local unions crafted ways to circumvent orders from DC by allowing only entry-level jobs to African Americans regardless of skill level and restricting any advancement. When pressed, unions created “auxiliary unions,” filling those with Black members who paid dues but received little protections or benefits.

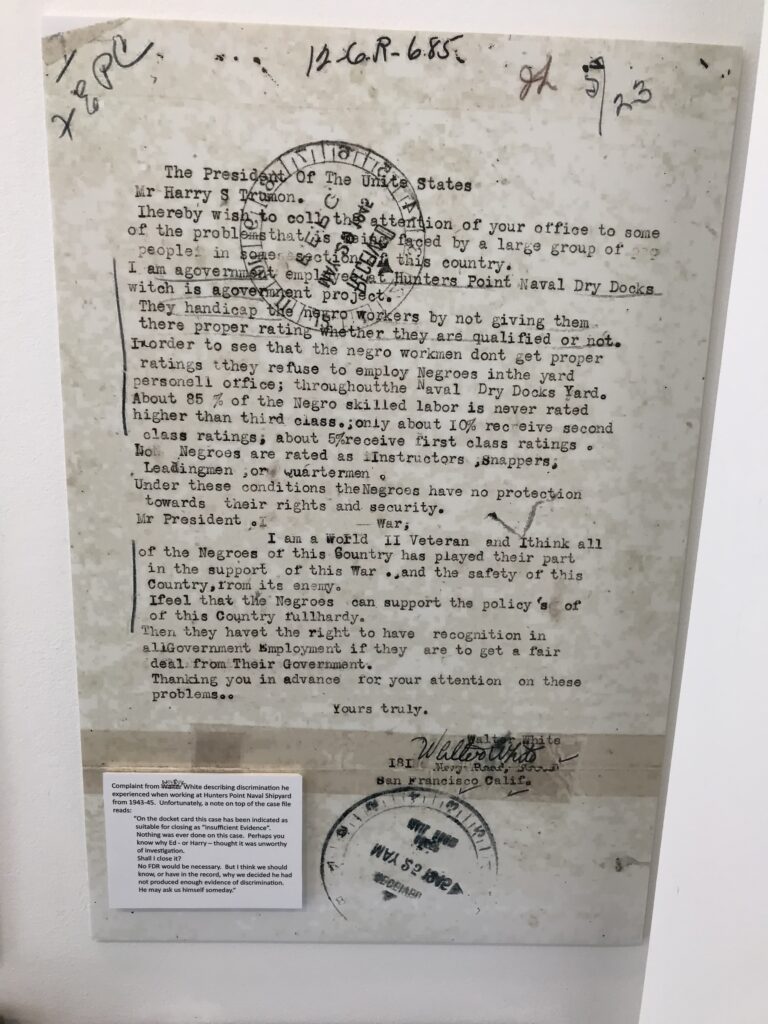

But the younger generation of African American men and women working at the shipyard in Carter’s photos wouldn’t put up with the discrimination their elders endured in the South. Carter shared several letters from Black shipyard workers pleading directly to FDR, including one from a man named Walter White.

“Mr. President, I am WWII veteran and I think all of the Negroes in this country have played their part in support of this war….they have the right to have recognition in all government employment if they are to get a fair deal from their government.” White’s case was closed due to “insufficient evidence,” but Carter’s display includes a note from someone working on the case.

“I think we should know, or have in the record, why we decided he had not produced enough evidence of discrimination. He may ask us himself one day.”

The curated slideshow mostly tells the tale of a lively place full of resolute workers, a community that rose to 18,000 at the height of the war, all bound by a common purpose. When the war ended, so did that common purpose, and as whites moved to the suburbs and other employment, African American workers, limited in real restate options by redlining and employment options by racism, held on until the shipyard closed in 1974.

Activists point to the closing of the shipyard, as well as the War on Drugs that lead to mass incarceration, as the near death blow to the small African American community still trying to hold onto a spot in San Francisco. The San Francisco Board of Supervisors formally apologized on Tuesday on behalf of San Francisco to “African Americans and their descendants for decades of systemic and structural discrimination, targeted acts of violence, atrocities, as well as committing to the rectification and redress of past policies and misdeeds.”

“San Francisco kind of abandoned the community, in my opinion,” Carter said, concluding the presentation. “But they are the most self-reliant people I have ever met.”

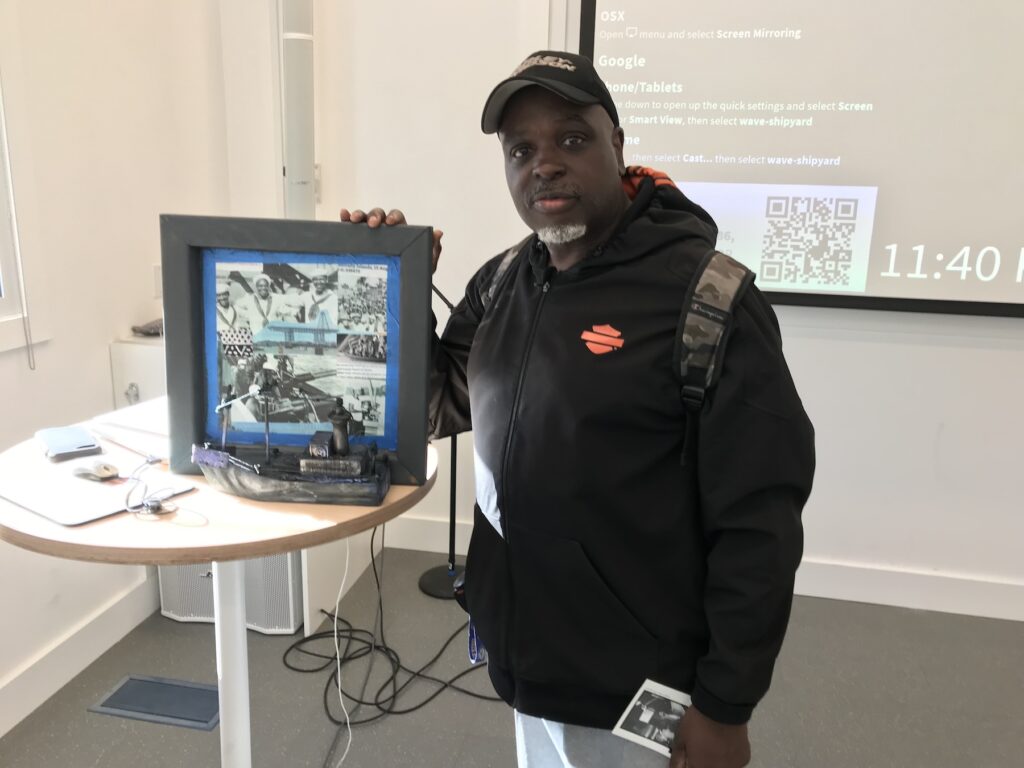

After the Q&A wrapped up, Hasseem Abdallah shared his own shipyard-inspired art with Carter. Abdallah, originally from Long Beach but a running back for the “late, great Mr. Rowen” of SF State in the late 1980s, was awarded a STAR Artist Residency in 2020 and, like Carter, has been enthralled by the shipyard ever since.

Abdallah’s choice of material, reclaimed wood, is inspired by his years of work with Bayview at-risk youth, resulting in a deep belief that life is about getting second chances.

“This place is horrible in some people’s eyes. But you look at this,” Abdallah said, referencing work inspired by Building 123, which will soon be torn down, “I don’t know exactly what element of this makes it beautiful. But this is beautiful.”

Abdallah, whose work is part of the “Black on Point” exhibition at Café Alma running through March 3, understands the complex past of the shipyard—a complexity that continues to thwart plans on what to do with it. He worked in the massive shipyards in Long Beach as a teenager during the summer, donning a hazmat suit and mask to spray paint anchors (“Everything was grey paint—that’s the only paint the Navy seems to have”), so the space between his imagination of what African Americans experienced at the Hunters Point Shipyard and the reality is a shorter trek than others.

And he personally remembers the fallout of the surrounding neighborhood after the shipyard closed: the unemployment leading to despair, the despair to drug abuse and crime, the crime to the massive incarceration from the disastrous War on Drugs.

“I mean, I went to a lot of funerals,” Abdallah said.

He’s grateful for his studio here, how he can hop on his motorcycle and leave the noise of his apartment on Sixth and Howard to wander in the eerie but inspiring shipyard.

“I get off my motorcycle here, and it’s like going back in time,” Abdallah said. “I started thinking, who was here? Those photos and everything that she (Carter) was showing, over18,000 people working here. I’ve never seen anything like that.”

“But I can feel their spirit here.”