By Tim Redmond

There’s a strange proposal making its way through the San Francisco planning process that would lead to the loss of 238 low-cost residential hotel units – and their replacement with a brand-new SRO building that some fear with not be affordable to low-income people.

The deal is really complicated, involving five hotels and seven properties, but it amounts to this:

A company called Boopie LLC, which is controlled by a Los Angeles real-estate development partnership, wants to get rid of 238 rent-controlled units and replace them with units that won’t be under rent control.

Existing tenants who are displaced will be offered lifetime leases – but in the long-term, there will be an undeniable loss of permanently affordable housing.

And along the way, Boopie will be able to test the waters to see if market-rate SRO units in the Tenderloin might appeal to, say, young tech workers who eat their meals at work, use company shuttles or bikes for transportation, and just need a place to sleep.

The plan has been under review for two years. If the city approves it, five hotels, most of which have both residential and tourist hotel units, would be converted entirely to tourist use.

That requires special permission and can only happen under limited conditions: The city has long protected SROs as a form of affordable housing that is available to people with very modest incomes.

Big money

But converting the SROs could be very lucrative – some of them are in the Union Square area, where boutique hotels are thriving. The Fusion Hotel, on Ellis Street, offers discounted tourist rooms at $269 a night, according to its website; the Fusion East, an SRO next door that would be converted, charges much less.

Weekly rents of $200-$300 – or up to $1,200 a month – are fairly typical for low-end residential hotels.

At $269 a night, assuming the current rate of about 80 percent occupancy, the rent for the Fusion comes to $6,456 a month. It’s safe to say that no SRO in San Francisco gets anywhere nefsar that kind of income.

But according to the city’s Residential Hotel Conversion Ordinance, SRO rooms can’t be demolished or converted unless they are replaced, one-for-one, or the developer pays a fee that’s supposed to be enough to build replacement affordable housing.

In this case, the project sponsor’s application notes, if the fee were paid “the availability of replacement rooms would be less certain.”

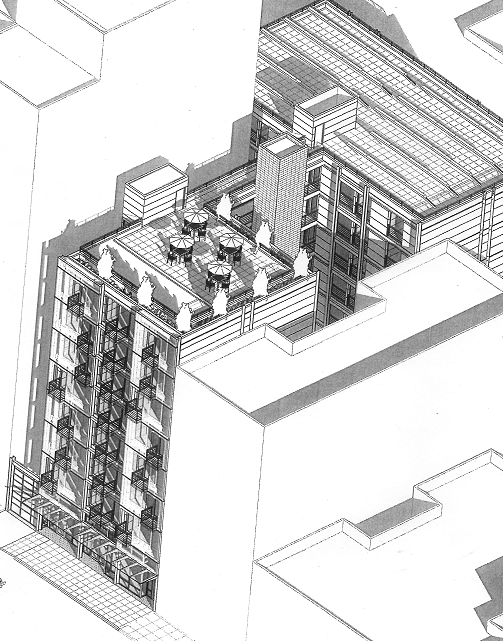

Instead, Boopie will construct two new eight-story buildings on adjacent lots that are now used for parking. Between them, the 351 Turk and 145 Leavenworth buildings will house exactly the same number of SRO units as the tourist conversion will destroy.

The ordinance mandates that the new rooms be “similar in size, services, rental amount and facilities, and which are located within the existing neighborhood or within a neighborhood with similar physical and socioeconomic conditions.” Most of that would apply to the new project – same neighborhood, same size. The new units would have individual bathrooms, but no kitchens.

However, the existing buildings are worth a lot more as tourist hotels than the new location is.

And the law, the application notes, “requires the replacement units to be comparable, not an identical match.”

There is nothing in the application that discusses what rent will be charged for the new units – when the building opens, or at any time in the future.

Randy Shaw, director of the Tenderloin Housing Clinic and an expert on the Residential Hotel Conversion Ordinance (which he helped write) told me that the existing tenants will, by law, be entitled to stay in their units until they decide to move out, and the rooms will only be converted to tourist hotels as they are vacated. It seems likely that the developer will offer buyouts, paying tenants a cash sum to leave so that their low-rent units can quickly be rented out to tourists at a much higher rate.

In comments to the city, Shaw noted that

The land value of both [new development] sites is less, and in some cases far less, than the sites of the applicant hotels. This requires an appraisal of all of the sites so that the replacement housing matches the economic value of the converted units…the excess value of the applicant hotels should be met by providing additional replacement housing, not a cash payment to the city.

The application describes the new development as “group housing.” There will be no parking for cars – but ample parking for bicycles.

The only statement about the cost of the new housing is this: The units will “be naturally affordable because of their size.” Most of the SRO units will offer between 238 and 246 square feet.

There’s nothing wrong with building a nice new SRO project, with clean, modern units with broadband access and a rooftop garden — if the units are, indeed, “naturally affordable.” Low-income people should have nice places to live, too.

But without rent control — or any limits on the rents that the owner can charge — it’s just a question of the “market” creating “natural affordability.” Will the location (close to mid-Market but not in a traditionally desirable neighborhood) really keep prices down to the level that typical SRO tenants can afford?

Or is this more “micro-units” than an SRO?

Behind Boopie

Boopie LLC, property records indicate, is controlled by DKR Partners in Los Angeles. The lead person on the project is Chris Rosas. Rosas didn’t respond to my emails or calls requesting information about the project.

There’s been a lot of discussion of “micro-units” in San Francisco, as the housing market becomes ever-more crazy and developers look for ways to cram even more units into the available envelope of a building. This is a step further: Most micro-units include at least a tiny kitchenette.

On the other hand, a lot of tech workers these days get all of their meals and most of the rest of their life’s amenities at work, so they might not need kitchens. It’s not clear who this new building will appeal to – but it’s unlikely that people who need truly affordable housing, with rent control, will be served by it.

And this much is clear: The new units – like all new residences constructed since 1979 – will be exempt from the city’s rent-control law.

Which means if the building proves popular, rents can go up at any time; the people who move in will have no long-term protection against rent hikes.

Land use lawyer Sue Hestor, who has reviewed the entire lengthy file, dashed off a few questions to City Planning Department staff:

I don’t remember seeing any description of the rents paid by residential tenants in the SRO units in the existing 5 hotels, or the nightly rate asked/charged for rooms during the 5 months/yr when Art 41 allows vacant rooms to be rented to tourists. This info is CLEARLY available to the owners of the 5 hotels.

Has it been requested? Provided?

What is the rate currently charged/asked of new residents of the SRO units? Of tourists for period May to September?

How many rooms have been vacant on average in weeks over the past year, or since this application was filed?

There may be an assumption that SROs rooms in the 2 new buildings will replace hsg already to tenants in the 5 SROs. How many tenants are expected to transfer into these 2 buildings? What rent will be charged to them? For new SRO tenants, what rent will be charged? For the 5 months of the year (May thru Sept) where rooms can be rented to tourists, what will be the nightly charge?

Does the owner of the 2 new buildings anticipate reaching agreements to temporarily house new or visiting tech employees? Have there been discussions by the developer?

We await answers.