The Planning Commission is ready to move forward on a potentially dramatic rezoning of some 30,000 building lots, many of them with housing already on them – although many of the commissioners had serious problems with the program.

After a lengthy hearing Thursday/21, the commission decided to continue the discussion for just four weeks. The planning staff had asked that it be delayed until April, so that more community outreach could be done. Even Commissioner Michael Antonini, who is among the most pro-development members of the panel, asked for another full hearing on the issue.

But Dennis Richards said that it was time to move this to the Board of Supes, and made the motion to continue to Feb. 25.

That was a bit odd, since Richards was one of the strongest critics of the plan and presented extensive information about some of the serious problems it might create.

Planning Director John Rahaim, possibly responding to this 48hills article, insisted that “this is not a program created by the Planning Department to destroy the West side of town or return to the era of Redevelopment.”

But there are endless problems when you decide to create an incentive to demolish what exists today to build something larger and denser.

There are a few hundred lots in the city that the Planning Department has identified as “soft sites” – places where there are old gas stations or other unused facilities that could easily be turned into new housing. Those places could accommodate the density bonus, planner say, with minimal disruption.

But the vast majority of the places where developers would get a bonus for building higher and deeper are sites where construction of the new would mean demolition of the old.

And the “old” is almost certainly either housing or existing businesses, or in many cases, both. In fact, small businesses are among the hidden victims of this plan – if you’re running a community-serving enterprise, and you have a long-term lease, demolition means the end of your shop – and there’s no guarantee in the law that you can move back in at all, much less at the same rent.

Antonini brought that point up, suggesting that project sponsors be required to give existing tenants a right of first refusal on the new space – but the new building might not have commercial space, might not have the same size space, and almost certainly won’t have the same price.

Among the other elements of the proposal that have received only modest attention but could have huge impacts: In many cases, projects that are built under the new rules could be appealed only to the Board of Appeals, not to the Board of Supervisors. The BOA is much less directly accountable, operates with less scrutiny, and some say it’s a less effective forum for the types of appeals that challenge neighborhood development.

The actual rules have gone through numerous versions and even some of the commissioners weren’t clear on what the proposal will actually mean. “The more time that we devote to this particular program, the more confused I get,” Commissioner Kathrin Moore said. “I think there’s too much for the few and too little for the many.”

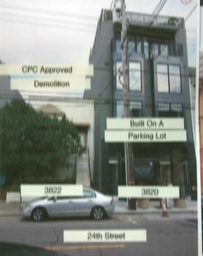

Commissioner Rich Hillis, who seemed overall supportive of the proposal, noted that “I don’t think that it works for every site. It works better for an empty gas station in the Sunset than a developed lot on 24th Street.”

Commission President Rodney Fong wondered the department staff should look at a plan that involves “no demolition of existing units.”

The most detailed comments, and concerns, came from Commissioner Dennis Richards, who started off by saying that the plan, like the Short-Term Rentals enforcement law, “is like an octopus with eight legs, you cut off a tentacle and another one comes around and wraps around our necks.”

His first issue: Even if the law were changed to ban the demolition of rent-controlled apartments, there might be a loophole for landlords who cleared out their tenants through the Ellis Act. Planning staffers told him that no building Ellised in the past five years would be eligible, but Richards said he would rather see “no buildings that were Ellised would ever be eligible. Period. Done.”

Then he put up a series of phots of buildings in Noe Valley that might be eligible for demolition under the law. “Some people think these soft sites only apply to gas stations,” he said. “There will be a rude awakening when the bulldozers come.”

Most of Noe Valley is in the zoning map where the density bonus would apply. A lot of small, pre-earthquake Victorian cottages are at risk. Some are protected by historic status; many are not.

“Why not just upzone the places where there is no housing?” he asked.

Richards also talked about the threats to small business, and planning officials responded that there will be “early notification” so that businesses can do “planning for relocation.” But neighborhood-serving businesses can’t just relocate to Berkeley or Vacaville, and in a lot of these commercial strips, there aren’t a lot of vacant storefronts.

That was a thread through all of the discussion: Why are we encouraging demolition of existing housing to create new housing, and how much will be affordable – to whom?

Housing activist Calvin Welch helped answer that question. The city uses regional data to create its Average Median Income, which determines the rate of affordable housing; the plan would allow units priced for households with up to 140 percent AMI to qualify for the bonus.

In San Francisco, Welch said, 2015 census figures show that median household income for white people is $104,000. For Asian households, the figure is $72,000; Latino, it’s $67,000. And the African American median is $29,000.

“Sixty four percent of this program is targeted to the lowest average median income,” Welch said. And since most of the new “affordable” units are for people with incomes of 120 to 140 percent of AMI, very few people in those neighborhoods will quality.

Richards acknowledged that the program could “create out-migration” – that is, force lower-income people out of town. Fred Shurburn-Zimmer, an organizer with the Housing Rights Committee, noted that every time a market-rate building gets proposed, “we hear from tenants that rents are going up, that they are fearing eviction.”

And yet, Richards said he wanted to get the program to the Board of Supervisors “as fast as possible.” So instead of waiting until April, instead of hearing more discussion and debate, a plan pretty much everyone agrees is deeply flawed will be back in Planning in a month. And unless the planning staff makes dramatic changes, there will be the same level of opposition.

And I can’t count six votes on the board for anything close to this proposal.