It’s Friday afternoon at the drop-in center known as Mother Brown’s on the corner of Jennings Street and Van Dyke Avenue. Despite the iron-gated door fronting the entrance, people stop by freely to check their mail, take a shower, do laundry, or chill out in the reception area. For a nominal fee, Mother Brown’s rents out lockers.

Gwendolyn Westbrook, the director of the United Council of Human Services — the official name of Mother Brown’s — as well as staff describe the place as a community center.

Client Johnny Scott likens Mother Brown’s to a family. “This here is a place where people get along,” he says. “There may be disagreements, but once it happens, we’re still friends, because we’re all family, and we know each other.”

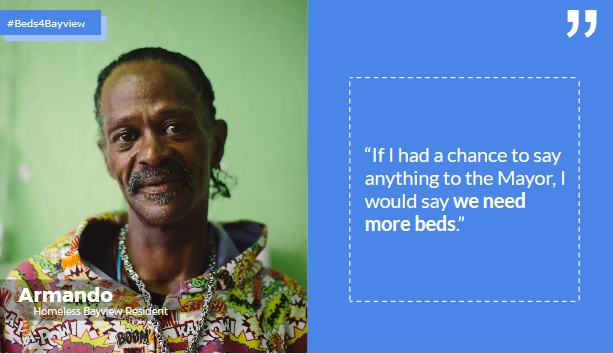

This community center serves residents in the largely African American neighborhood of Bayview-Hunters Point, many of whom are experiencing homelessness. According to the Homeless Emergency Service Providers Association, the neighborhood has 40 percent of the city’s homeless population, yet provides only seven percent of homeless services.

It’s because of this disparity that the service providers’ organization recommends that a full-service, 24-hour shelter open in the Bayview and accommodate 100 people, and has requested the city to allocate $3.2 million to address it.

Though clients have been known to stay overnight on the second floor, technically Mother Brown’s is not a shelter. It operates a drop-in center where up to 55 people wait — seated in plastic chairs — for an available shelter bed.

The neighborhood’s only other service provider is an overnight shelter at the Providence Baptist Church on McKinnon Avenue. If Mother Brown’s isn’t a shelter per se, then Providence is barely one; it’s low-threshold and accommodates up to 110 men and women and an average of three families, though it rarely fills to capacity. Providence is far-flung in relation to the more centrally located shelters in city. Also, instead of beds, the facility lays out mats on the gym floor, and it provides no showers or storage — only recently, Providence started serving breakfast to guests before their mandatory 6:30 a.m. exit.

A clear need

But Melissa Whitehouse, budget director in the Mayor’s Office of Public Policy and Finance, said the upcoming budget won’t include funding for a Bayview shelter. She added that money is available for a family resource center in the neighborhood, as well as drop-in centers and rental subsidies for homeless people. Whitehouse also said that $2.5 million is being dedicated to the recently opened Navigation Center in the nearby Dogpatch neighborhood. However, the length of stay in the Navigation Centers have been reduced from an indefinite period until housing is found to 30 days. If residents don’t access housing within that time frame — and many don’t — it’s back to the streets they go.

Meanwhile, the health of people sitting at Mother Brown’s is at risk.

“They’re sick, and they’re getting sicker,” Westbrook says, citing such ailments as swollen legs and breathing difficulties. “They are dying on the streets and there’s nothing we could do about it. It’s really heartbreaking.”

While airline passengers are inconvenienced from reclining on a seat during red-eye flights, people waiting for a shelter bed must contort their bodies while seated for hours, an especially difficult situation for seniors and people with disabilities. The lights aren’t even turned off after dark. The gymnastics performed on a hard-plastic chair aggravates chronic conditions, says Wanda Jean Richardson, a 46-year-old homeless woman.

“(Sitting) is not good for me because of my stroke, or for elderly people or anybody out there. It messes up your legs and stuff,” she says.

Collectively, two supervisorial districts in San Francisco account for at least two-thirds of the overall homeless population in the 2010s: District 6 in the central area of the city, and the Bayview’s District 10 in the southeastern portion. In 2015, the last year when the City released its statistics on homelessness, District 10 was estimated to have more than 1,200 people living without a permanent roof over them.

Why does the Bayview lack suitable amenities for homeless people if it clearly needs them?

“Racism, they don’t give a damn about us. What else could it be?” says Westbrook.

The lack of investment in homeless services in the Bayview is the result of a long legacy of racial segregation, real estate speculation, destruction of public housing, and mass incarceration in San Francisco — and the United States. Westbrook says that she sees this legacy in play.

“We’re on the outskirts of San Francisco. There’s not a lot of tourists (here), so it’s out of sight, out of mind.”

The 27 service providers comprising HESPA agree that the city should close racial gaps: They propose funding for an African American-run organization to run a Bayview shelter.

But opening a much needed shelter with appropriate support services — such as case management, mental health counseling and housing referrals provided by trained, culturally competent staff — might be more easily said than done.

Especially, when neighborhood politics rears its head, and that killed a planned shelter just two years ago.

Political opposition

In 2012, the city’s Human Services Agency was awarded an almost $1 million state grant to convert an empty space occupying the same building as Mother Brown’s into a shelter. The hope was to create a 100-bed shelter, but it met with resistance.

Supervisor Malia Cohen, who represents District 10, reported being shocked to hear about a new Bayview shelter during Mayor Ed Lee’s State of the City address in January 2013.

The Board of Supervisors’ vote to accept the grant at their November 19, 2013 meeting was a mere formality, but that didn’t stop Cohen — with fellow supervisor Katy Tang — from voting against it. “My opposition has nothing to with being anti-homeless or being Nimby,” she said. “We should be having a citywide conversation.”

Bayview Residents Improving Their Environment, an organization formed in 2011 by professionals and mostly newer residents engaged in neighborhood beautification projects, cried foul as well. Businesses in the Bayview, including members of BRITE’s business alliance, also filed suit in May 2014. They claimed that the city inadequately informed residents of the proposal. According to the suit, the area is zoned for light-industrial use, making the site improper for a shelter.

Ultimately, the plan was withdrawn the following year, when the city realized that completing the project required an additional $3 million from the local coffers.

Like the people from BRITE and the lawsuit plaintiffs, Cohen cited a lack of community notice. She also said that the city has already overburdened her district with homeless and low-income services, despite District 10’s demographics.

“While there are undoubtedly a significant number of individuals that are in desperate need of emergency shelter and long-term housing, the plan for 2115 Jennings Avenue [sic] was flawed from its inception,” Cohen said in a 2015 statement. “For years, the Bayview community has been forced to carry a bulk of many of San Francisco’s supportive services. The idea to build a 100-bed shelter was another example of a unilateral decision by the city that completely lacked any real community process or input.”

As of press time, Cohen has not responded to multiple requests for comment on the HESPA proposal.

Staying in 94124

A comparable sum of money to what was required for Jennings Street site — $3,263,586 — could cover costs for a new shelter, according to the HESPA plan. The $3.2 million providers are asking for would fund the shelter $635,088 over three months in the 2018 fiscal year and $2,628,498 for the following year. Using capital funds allotted from a 2016 local ballot measure could make that possible, the providers said.

In the meantime, Gwendolyn Westbrook is eyeing a vacant warehouse on Toland Street as a potential site for a Bayview shelter. “If we could get it rehabbed, it would be outstanding and still be in 94124,” she says, referring to the area ZIP code. The Evans Street building where a Parisian bakery produced and sold sourdough bread until its 2005 closure would also be convenient, she says.

But Westbrook also finds the runaround just to find an accommodating place for homeless San Franciscans belying the city’s image of a welcoming, accepting place.

“They say San Francisco is one of the most liberal places in the world, but there’s no compassion for this community,” she says. It’s sickening to see the way people are being treated.”

This story also appears in the Street Sheet.