SAN FRANCISCO — Police commissioners unanimously voted to pass a resolution Wednesday to address homelessness through healthcare professionals and social workers rather than police.

The resolution calls on the mayor and Board of Supervisors to convene a stakeholder group to develop alternatives to the current police-led response to homelessness. The stakeholder group would include the Department of Homelessness, the Police Department, community organizations and homeless people.

When somebody calls the city to complain about homelessness people or encampments, SFPD is the primary agency dispatched in response. From 2016 to 2019, the number of police officers devoted to responding to homelessness has more than tripled.

“A police response can be inhumane. Police officers don’t have access to housing and treatment. At best, they can move people along,” said Jennifer Friedenbach, executive director of the Coalition on Homelessness, at the meeting.

That, in turn, can exacerbate a whole myriad of issues that, making it even more difficult to exit homelessness: mental health, trauma, losing contact with social workers who have housing lined up with them, losing their belongings and documentation.

Citing the 2015 US Interagency Council on Homelessness, the resolution recommends that the linking of homeless people with an appropriate level of housing is the only lasting solution.

In January 2018, the city created the Healthy Streets Operation Center to address the public’s homelessness-related issues through the coordination of multiple city agencies. But if its main goal was to stem 311 calls regarding homelessness, the majority which are regarding tent encampments, it may have done just the opposite: from January to October of last year, there was a 31 percent increase in tents.

That is, in large part, because homeless San Franciscans literally have no where to go. Robert Ponce, 37, has experienced multiple encounters with the police, sometimes even a few in the same day: “A lot of times SFPD tells us to get out of the neighborhood and go somewhere else.”

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

But when shelters remain full, with a waitlist of more than 1000 people, and there are over 5,000 unsheltered homeless individuals on the city’s streets, the answer isn’t clear to anybody as to what that “somewhere else” actually is.

For Ponce, it’s “down the block, around the corner.”

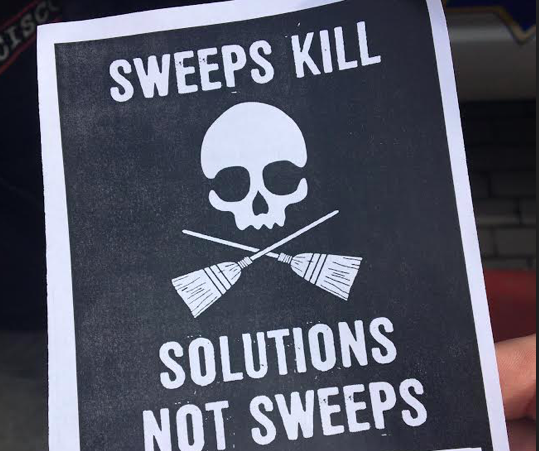

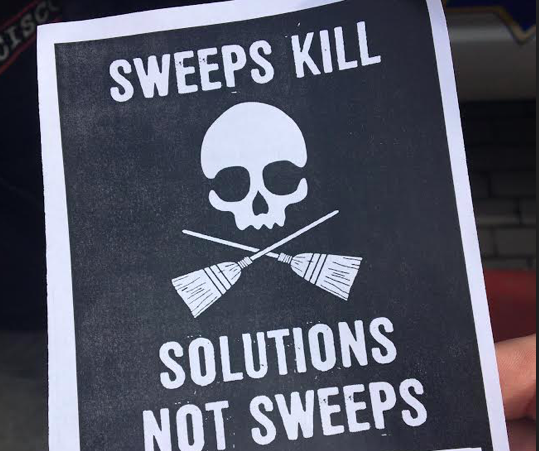

On the same day, faith groups, healthcare workers, and homeless advocates launched a campaign demanding an end to homeless sweeps and the police response to homelessness. The campaign, Solutions Not Sweeps, additionally calls on the city to eliminate the confiscation and destruction of people’s personal belongings and the towing of vehicles that people are using as their homes.

Says Leilani Farha, United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Housing, who has endorsed the campaign: “Sweeping people off the streets and thus forcibly removing them from their homes, whether they live in tents on sidewalks or in their cars, is cruel and inhumane treatment.”

Depending on the location, homeless sweeps can occur multiple times a week, often early in the morning, forcibly removing homeless people from sidewalks and underpasses. DPW workers have also thrown away homeless residents’ life sustaining belongings, including medication, sleeping bags, and personal documentation needed to access housing and healthcare. The end goal, advocates say, is to ensure that homeless people and their things are out of public view — not to seriously help people exit homelessness.

In prior months leading up to the campaign, several city officials and organizations have denounced sweeps, including the San Francisco Democratic Party and Supervisors Dean Preston and Sandra Lee Fewer.

Many have called on the city to make investments in shelter and housing as an alternative to the sweeps, which are both costly and ineffective. More than that, there is the cost of sustained human suffering.

“If you want people to move, then you should move them into some place. All you did was move me onto the sidewalk corner for all the world to see that I am homeless and I am suffering,” says 36 year old homeless mother Victoria Collier.

Demands to end homeless sweeps are echoed by homeless advocates across the nation. According to a 2019 report by the National Law Center for Homelessness and Poverty, nearly three in four cities ban camping in public. These bans occur despite a severe lack of shelter and housing for homeless residents.

However, homeless advocates garnered a big win with the US Supreme Court decision not to review — and therefore uphold — theMartin v. Boise 9th Circuit ruling.The ruling maintains that it is cruel and unusual punishment for cities to arrest or fine homeless people for sleeping outside if no shelter is available.

Recently, a Denver judge cited that same ruling to pronounce the city’s urban camping ban unconstitutional. The Denver has already appealed the ruling.

In San Francisco, homeless czar Jeff Kositsky has said that the 9th Circuit ruling is a “non-issue” because the city already complies by offering shelter to homeless people before an encampment sweep, but according to Collier, “They offered me nothing. Not even a plastic bag to put my stuff in.”

In addition to cities’ non-compliance with the 9th Circuit ruling, advocates say the ruling doesn’t go far enough in its protections of homeless people. Police still have a whole host of other laws to evict homeless people from the public, and cities can comply simply by offering shelter beds that last less than a day.

Homeless San Franciscans have yet to file their own case in court.