Teaching Behind the Mask is a series of voices from infant, toddler, and pre-school classrooms across San Francisco. It’s a collaboration between Barbra Blender, Eliana Elias, and the remarkable early-childhood education teachers who continue to serve children and families during the pandemic. Read previous installments here, here, and here.

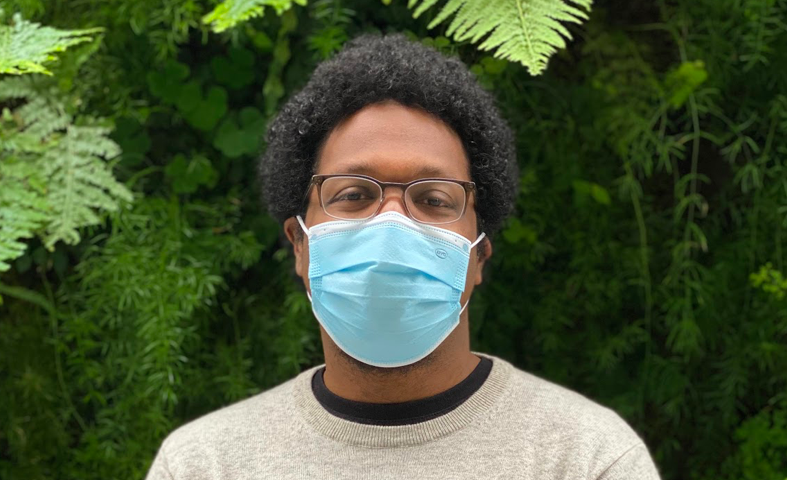

My name is Chandler Graddick. I have attended public and private schools throughout my career as a student. I have also taught in both public and private Early Childhood Education programs. Through these reflections I invite you to look through a small window into how these experiences helped shape my perspectives an African American male educator.

Please join me is revisiting my past and present experiences. Together we can dream about a better future for all children and Early Childhood Education teachers… in private and publicly funded schools throughout the San Francisco Bay Area and the country.

On mentors and role models…

I had an amazing high school teacher: Mr. Compton. I was a sophomore in a San Francisco Catholic high school.

Mr. Compton was a military vet who went to West Point. He didn’t play around. I started to build this habit of arriving early to his classes, so I could get extra help with my homework.

We would often be assigned a question that no one knew how to solve. One early morning, I went for help and he taught me. Class started and he challenged our class with a problem. I still remember the sliding chalk walls. He wrote down the problem we did earlier that morning and invited students to solve it. After all the other students tried solving it, I was invited to the board. I went up front, slightly nervous and shared my answer and reasoning and my peers’ voices echoed through the classroom: “Ohhhh, awwww, that’s how you do it! Right on Chandler!”

I looked over at Mr. Compton. He was just leaning on his chair, arms folded across his chest, a smirk on his face. He looked at me and said: “Here is a future teacher in the making….!”

The 15-year-old Chandler said cynically under his breath: “Yeah, right.” Yet, here I am confirming my high school teacher Mr. Compton’s prediction.

This highlights a very important lesson I will never forget…my teacher was giving me the tools to succeed, a chance to demonstrate my intellect and shine in front of my peers.

Can I become a Mr. Compton to others?…

In that small moment, Mr. Compton made a difference in my life. I did not know at the time but now I know that the confidence that he planted in me made me want to be a role model to children. I grew to want to show children that African American males are not just what they see on TV. Not all of us are the same. We are not just athletes and celebrities and the central pieces in negative media stories. We come in all forms: educated, dorks, geeks, athletes, physicians, educators, rocket scientists, military men. I want children to experience different types of African American males. I want them to see me for what I am: well-mannered and communicative. A thoughtful educator. An educator who cares about children and families.

Overcoming stereotypes and the courage to promote change…

One would think that in 2021 we would have made progress in debunking stereotypes. After all we have had Barack Obama in office, and many other visible African American role models.

Yet, if I were to advise a young Black male coming to the field of Early Childhood, I would warn him of a painful truth: “Some children will be afraid of you and some families will not trust you.” I have personally experienced this. Not too long ago, I had one child that screamed at me for three weeks straight. I learned to have patience. I kept building a positive relationship. I know that the first two to three weeks can be stressful, but in my case, it was nerve wracking.

Another stressful situation happened soon after: I had one family of a different racial group question why their daughter was in my group rather than my co-teacher’s. I’m not 100 percent sure that their lack of confidence in me was motivated by biases, but I was surprised that a family made that judgement without knowing me. I had a BA in child development, and I had dedicated my life to children. Surely that should have been enough to qualify me, right?

This situation motivated me to develop the most precious relationship with that family. I said to myself “I’m going to show this family that I’m worth it!” Within a few weeks, I had developed a very strong relationship with the child. I was told that she would go home every day saying: “Mr. Chandler said this, Mr. Chandler said that.” And when she graduated from our preschool, the family gave me flowers and pictures of me and her.

I see my investment in children and families as a tool to change the biased narrative that is still so common against African American males, particularly those of us who follow our calling to teach young children. I celebrate my small victories, as I think of them as changes in the fabric of our society. Yea. It is worth it…

My personal experiences shape my goals for children in my care…

I had a chance to have a well-rounded education. I went to public schools from kindergarten through eighth grade and then to a private high school and San Jose State for my BA. Even though I had many challenges at school, I can say that school helped me learn how to be an adult, to think for myself, to problem solve, to explore possibilities and to open my mind.

At first, I was going to be a computer engineering major, but I ended up taking a summer GE course in child development at SFSU and saw my path to being a teacher… and confirming Mr. Compton’s prediction.

In first grade I started showing signs of learning differences. Unfortunately, those were not solved until high school. My parents had to pay thousands of dollars to do tests on me because the SFUSD system did not appropriately address the issues, perhaps for lack of resources or appropriate diagnosing.

I went through years and years grueling night routines: staying up late with my parents, going over the things I did not understand during the day at school. I wasn’t officially diagnosed and appropriately supported until high school. By the time I was fully supported, my grades shot up. I was not struggling in class. I was learning and understanding what I was being taught and after all these years without being diagnosed, I was having fun in school.

The public K-8 sector let me down. It was very tough for me and my parents. With appropriate diagnosis, families are able to pinpoint differences in their children’s learning styles and receive the help they need. I did not receive that help. I wish things had been different.

As an African American adult male, I have more awareness of how Black men are stripped of all their power. The system has been stripping Black males of their power and their rights. Stripping them of their humanity, of their will. Video cameras on phones have allowed us to now document what happens to many individuals and this is a positive change. Before the technology was available, few could confirm and witnessed what happened to people of color. This advancement in technology made it possible to see the entire sequence of these horrific events, from beginning, middle to end which exemplifies that black or POC have been at a HUGE disadvantage, they’re been portrayed as evil people and they are falsely accused of things they have not done.

Public and private: navigating two worlds

In the subsidized programs where I have worked, I was thankful for the team of cooks who make breakfast, lunch and snacks for the kids based on USDA guidelines. In those programs, many children did not have a proper meal before coming to school. Often, this resulted in lack of self-regulation for some of the children. Some children displayed sadness, frustration, and anger.

Our curriculum focused on the children’s social and emotional growth. We wanted to provide them with the skills to succeed in elementary school: ability to focus, to express themselves and to engage with peers. Those programs also had supports for children who need additional help: a mental health specialist and an educational coach. I found those extra supports very helpful. Most of the families in those programs do not have the resources to hire specialists to work with their children, and most teachers in those programs need extra support. These extra supports gave us more opportunities to address the inequities caused by the income disparities that exist in our city.

However, challenges persisted: low pay and stressful working conditions translates into limited stability in classrooms. Teacher turn over in those programs was very high. Children may have two-to-three years at preschool and three different teachers. This “revolving door” will not give our most vulnerable children the opportunity for a strong attachment and someone to really understand them. They may think the teacher left because of them.

High teacher turnover rates are stopping us from meeting the children’s needs. If there isn’t a consistent teacher for children to build a relationship with, children may enter elementary school without the self-confidence they need to become effective learners. Instead, they might exhibit challenging behaviors, trust issues, poor social skills and ineffective communication skills. There is a growing body of evidence linking high turn-over in Early Childhood Education Program with children’s later school success. We must address this issue if, as a society, we really want to tackle the inequities that impact our youngest learners.

My experience with private schools helped me see how these two worlds diverge. From my experience, children who come from economically advantaged backgrounds are showing up at schools well fed. They often can self-regulate and, therefore, they are ready to learn. I hardly hear much crying and children seem to be attentive and focused. The schedule is consistent, enriched and offers many opportunities to develop academic skills. Teachers have a BAs and the workforce is more stable. This stability helps teachers stay on the job longer and acquire lots of experience. This ultimately helps improve the children’s educational experience.

Teachers who remain in the field a long time develop strategies, experience and skills with a wide range of kids. This experience prepares them to better serve children with higher needs.

We need a balance between publicly funded and privately funded models. As a society, we must continue to work to improve this system, making it more balanced, and equitable. If we don’t do this, we perpetuate a system which only makes the distance between the haves and have nots more visible: on one side 4 and 5 year-olds exceeding academically, exposed to stable teaching teams and preparing themselves to be learners and on the other children and teachers struggling to deal with an uneven system, resulting in lack of opportunities. This isn’t right.

The need for change and recognition, and working during a pandemic

Families are pleading for early care and education to expand. The pandemic has exposed the fundamental role that early care and education plays in our society.

Families needed schools to reopen so they could have their jobs. Early Care and educational professionals rolled up their sleeves and reopened their programs, even when the COVID death toll was rising. ECE teachers through San Francisco answered the call. Now we do need something in return: We want to be seen as professionals. We need acknowledgement from the president, Senate, House leaders, our state representatives and our local leaders. We often feel like people don’t really care about early childhood teachers. Our jobs are not taken seriously.

We have put our lives at risk. The possibility of catching COVID and dying is real for us every day. We can’t care for children from a hospital bed… we can’t care for them if we are dying.

I am happy the vaccine slowly becoming available to us. I am grateful to all the scientists around the world who have developed vaccines. I hope teachers, children and families will have access soon. This will help us all continue our important work educating our youngest learners, no matter the setting.