This past Sunday morning, the eastern slope of San Bruno Mountain hosted a dreamy scene, a fairy tale from pre-pandemic days. Families frolicked to live music and shared a meal for a good cause, and the social joy was as palpable as the fragrance of the native plant starters for sale. The annual San Bruno Mountain Watch Pancake Breakfast Fundraiser was an undeniable hit.

San Bruno Mountain is often overlooked, about a third of the height of Diablo, half the size of Tam, and garnering about one-twelfth the local interest of its more famous neighbors. But as the world wrangles over what to do about climate change, San Bruno Mountain’s near decapitation a half-century ago is a lesson about how to fight it.

“It’s been fifty years since the local people fought to save this mountain,” David Schooley, one of the founders of San Bruno Mountain Watch said. “We need to rise to that level of concern again because we are facing disasters everywhere.”

Wearing a black mask and matching black hat, Schooley sat at a round white table covered with his numerous books on San Bruno Mountain, including Ravines of the Heart. Emanating a Muir mystique and deep love of the mountain, Schooley’s life has two acts: a) find a place in nature you love, and b) devote the rest of your life to its preservation.

Schooley delights in the irony that preserved the amazing ecosystem of San Bruno Mountain in the first place, which includes sand dunes harboring federally endangered Lessingia plant (Lessingia germanorum); the endangered San Bruno Elfin Butterfly (Callophrys mossii bayensis); and countless acres of critical habitat for a diverse array of unique flora and fauna.

As San Francisco grew by leaps and bounds in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the base of the mountain became a dumping ground. The stench discouraged human encroachment, protecting the mountain from development and destruction.

“That stench and that horror saved the mountain. Nobody wanted to build up there. That’s why there are 13 rare and endangered species on it today.”

When he discovered the hidden wonders of San Bruno Mountain in the late 1960s (“Canyons right next to the Cow Palace! Couldn’t believe it!”), Schooley heard about the plan to demolish the peak for Bay fill and knew he had to help stop it. He credits the work of Save the Bay in those early days, as well.

Through the efforts of these activists and others, the San Bruno Elfin Butterfly and also-rare Mission Blue Butterfly were placed on the Endangered Species list in 1976, and lawsuits and community pressure led the area-owning Crocker Land Company to give and sell San Mateo County 1656 acres to establish San Bruno Mountain County Park. The State of California later expanded the park to 1900 acres.

When asked about the “code red” warnings of the recent IPCC Climate Report, as well as the ambitious state and national “30 by ‘30” plan to save 30 percent of ocean and land by 2030, Schooley concedes to the challenges. But he adds that things didn’t seem so swell in his days, either.

“I thought the world was hopeless because of nuclear weapons. We’d have drills where we ducked under tables every other day because the bomb was coming. So I went to nature, the wild, as the only answer.”

Anne Kircher, secretary to the Board of Directors of San Bruno Mountain Watch, shares Schooley’s exuberance, mixed with a pragmatism from her background in biology. When the “30 by ‘30” plan is mentioned, her bright eyes shine with an energy as cheery as her blue blouse.

“’30 by ’30’ is a noble goal because otherwise these places will bite the dust in population expansion.”

Kircher explained the biological concept of diverse ecosystems like San Bruno Mountain being complex, and that complexity often leads to stability.

“That’s a general biological tenet. If something happens—let’s say a species dies out because a virus gets in—if you have a lot of diversity, there are other kinds of organisms that can move in and fill that niche.”

Kircher said that if we can protect these islands of biodiversity with denser housing concentrated around, that would at least keep the few remaining places like San Bruno “more sacrosanct.”

“We are hard-wired in our ancient minds to love nature. Golden Gate Park is a beautiful park, but it’s not the same. It’s still humans putting their imprint on it. So I really support the idea of “30 by ’30”. And I think part of it is—can I use this word?—soul. What it does for our souls.”

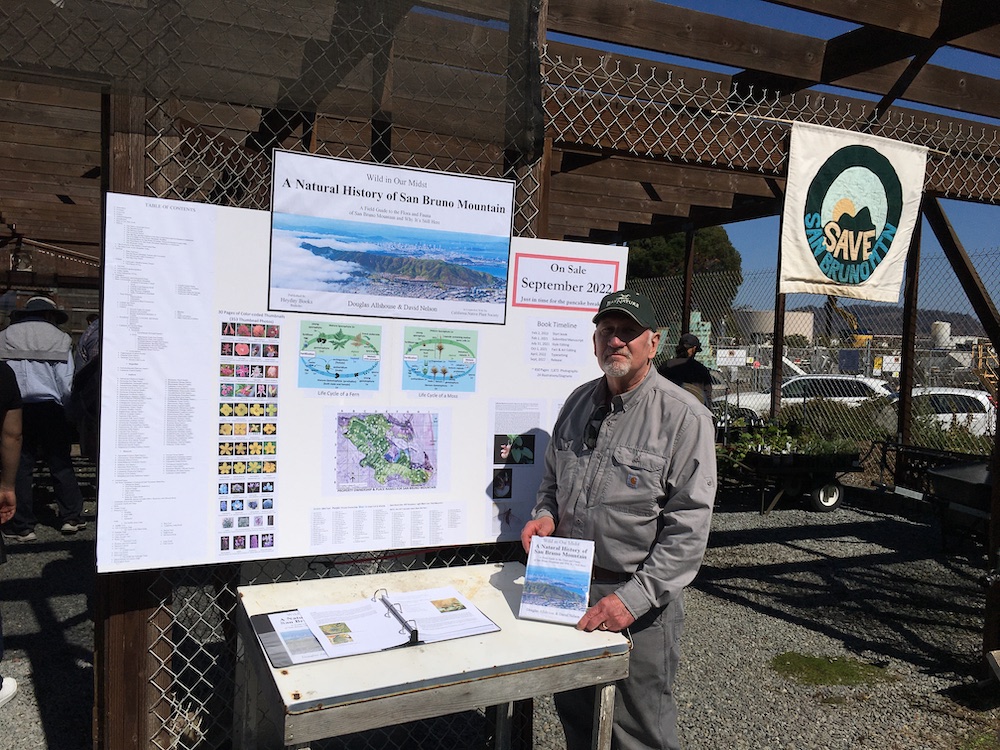

Doug Allshouse, co-author with David Nelson of the forthcoming book The Natural History of the San Bruno Mountains (HeyDay Press 2022), stands before a whiteboard loaded with San Bruno Mountain history, ready to sell.

“The important thing to remember about San Bruno Mountain is that it’s the last remaining vestige of what the northern peninsula looked like before the arrival of the Spanish. With Spanish came cattle and new weeds, so the mountain now is about 40% non-native. About 250 years ago it was 100% native.”

The Native Americans understood the value of the San Bruno Mountain ecosystem; Allshouse said that in a modern, dense urban place desperate for housing like the Bay Area, the value of the mountain has to be taught—and defended.

“With our book, we want to teach people to understand what they’re looking at. Once you put a name to something, you never look at it the same way. I pointed out a monkey flower to my wife, and now every time on the mountain, my wife is asking where her monkey flower is.”

“When you learn how something contributes to your own ecosystem—a lot of these plants are edible or have medicinal value—you don’t forget that value.”

Allshouse points to the long muscular body of San Bruno Mountain and asks the reporter to imagine the scene today if the decapitation plan had gone through.

Roughly 600 feet of the grey sandstone peak would have been quarried out, 350 million cubic yards of rock sloughed onto a massive conveyor belt down to Candlestick Point and loaded onto barges to fill the bay all the way to Redwood City. The new land would have been called New Manhattan, one more slight to the Ohlone population who called San Bruno Mountain home for generations.

“Picture it being about half as high. All that fog and wind banked up on the other side would be on us now.”

Although imagining a shivering accordion player and families wrapped in blankets instead of enjoying pancakes in the warm sun was distressing, the real desecration would have been another step in the destruction of nature—the destruction of ourselves—while thinking we were making progress.

“We used to live in these ecosystems, and not on them,” Allshouse said.