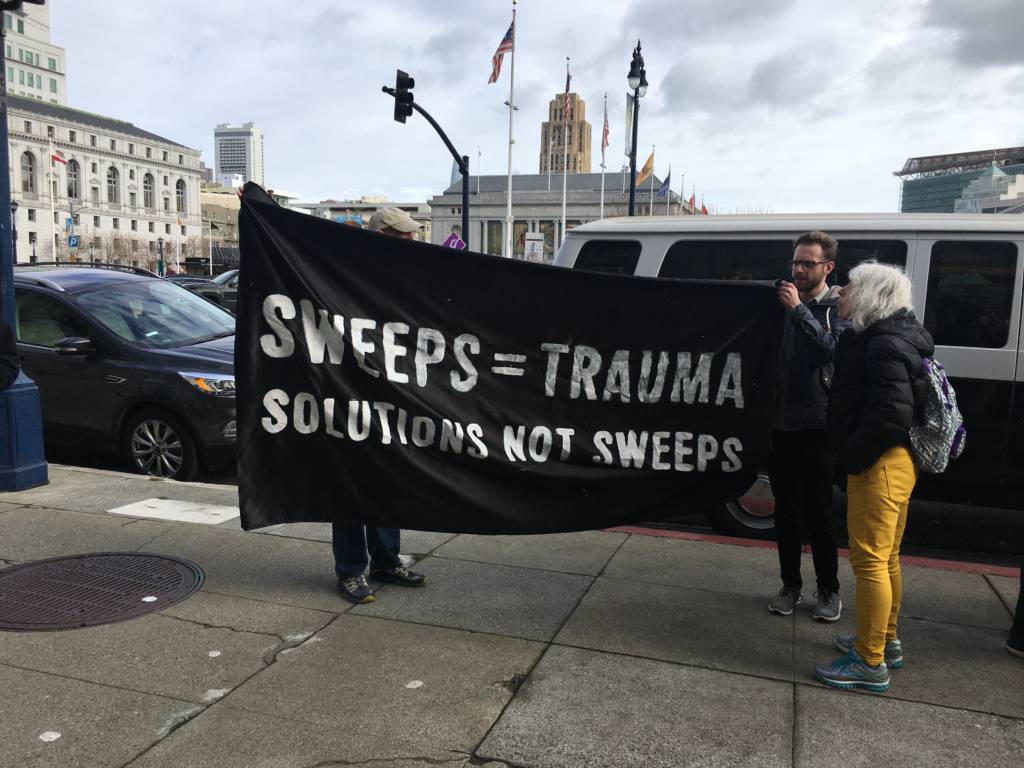

The Coalition on Homelessness and two legal nonprofits filed suit today against San Francisco and Mayor London Breed, alleging that the city has failed to provide affordable housing for homeless people and continues to criminalize them with illegal sweeps.

The Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights and the ACLU filed the complaint in federal court seeking an injunction to halt the sweeps, cease the confiscation of the possessions of the unhoused, and end discrimination against unhoused people.

On a much larger level, the suit makes clear that the city has failed to provide enough affordable housing for people who are living on the streets.

It directly points to the mayor as a part of the problem: “In her remarks and actions, Mayor London Breed has also raised the specter that unhoused people are a blight to be removed from sight.”

If a federal judge agrees, the case could have a dramatic impact on the way San Francisco addresses homelessness.

The legal documents include dramatic and extensive new evidence that the city is violating its own laws. As the Lawyer’s Committee notes:

Over a six month period, 1,200 unhoused people were displaced by street sweeping teams even though for 80 percent of those days, the city had no shelter to offer them (against Prop. Q requirements); only 100 items were stored by DPW in the entire time period (violating the city’s laws on 90-day storage of all confiscated property); and over the past three years, at least 3,000 unhoused people have been cited or arrested for sleeping in public despite the fact that the city has no shelter to offer them.

From the complaint:

San Francisco presents the image of a caring municipality with a concrete plan to address the root causes of homelessness. But in reality, the City’s decades-long failure to adequately invest in affordable housing and shelter has left many thousands of its residents unhoused, forcing them to use tents and vehicles as shelter. In the face of this mounting crisis, the City has marshalled significant resources toward unlawful and ineffective punishment rather than affordable housing and shelter.

“The city says it’s helping most homeless people,” Zal Shroff, a lawyer with the LCCR, told me. “They say a few bad apples are causing problems. But that is patently false.”

In fact, he said, data compiled for the case shows that the city is making homelessness worse: “People who could have had a brief experience with homelessness are seeing their ability to get off the streets destroyed.”

From the complaint:

The current homelessness crisis in San Francisco is the result of decades of failed economic policies that led to dramatic wealth inequality, an unprecedented housing shortage fueled by racism, and the defunding of social services programs—leaving many San Franciscans in crisis. Despite awareness of these root causes, the City is using unhoused residents as the scapegoats for a crisis of economic and racial justice that it helped to create. San Francisco should fight to end homelessness.

Instead,

Through the Healthy Streets Operation Center, the City has embarked on a campaign of driving its unsheltered residents out of town—or at least out of sight—in violation of their constitutional rights. Specifically, the City has a custom and practice of citing, fining, and arresting—as well as threatening to cite, fine, and arrest—unsheltered persons to force them to “move along” from public sidewalks and parks. The City targets unhoused people throughout the City at the request of select City employees and more privileged members of the public. Because San Francisco does not have—and has never had—enough shelter to offer to thousands of its unhoused residents, the City is punishing residents who have nowhere to go. … Although San Francisco purports to stockpile enough shelter beds to offer each of the individuals it targets through its perverse practice of criminal enforcement, the City openly admits that it deliberately targets homeless people knowing that it only has shelter for about 40 percent of them. When shelter is possibly available, the City only offers it, if at all, as an afterthought to the few unhoused residents who remain hours after the City has forced all other unhoused residents

For years, Mayor London Breed has celebrated the HSOC program, praised its supposed success, and sought additional funding for it.

The legal documents include devastating declarations from unhoused and formerly unhoused people who have faced the brutality of live under the Breed Administration. Toro Castano, who has a master’s degree in Art and Curatorial Practices and has worked at several museums, was unhoused because his housemate lost the place and he was unemployed. He lived on the streets from 2019 to 2021.

I was harassed by San Francisco Police Department (SFPD) and Department of Public Works (DPW) staff several times a week for the entirety of the two years I was homeless. For the majority of that time, I stayed with 6 or 7 other homeless individuals near 16th Street and Market Street in the Castro District—just in front of the AIDS Memorial Mural. Nearly every morning, public works crews would come wake us up and tell us we had to move. We were just expected to break camp and leave. If we didn’t move, police officers were called and we were threatened with arrest for illegal camping. I never recall anyone offering us services or shelter. 6. This was a traumatic process. Often, crews would come wake us up at 4:30AM. They would spray large volumes of water and chemicals on us or near us that would damage our property. One time, they sprayed an extremely pungent deodorizer on the street that lasted for days and was extremely unpleasant—with the goal of making it so we could not return. We almost never got any notice from public works crews or the police before these daily sweeps. 7. It is hard to articulate how battering this experience can be. I lived with the constant fear that I would lose the few possessions I had to survive. We were at the mercy of the individual crew members or officers who would show up on that day. Usually after all this commotion, they would just force us to move right across the street—only to do the exact same thing to us again the next day. It felt like this was just to punish us for being homeless.

I personally witnessed my property being destroyed by the City of San Francisco at least 4 times in the two years I was homeless. Three of these times were earlier in the pandemic. I was staying at the corner of Noe and Market, Collingwood and Market, and Sanchez and Market, respectively. On each of these occasions, public works crews came and told us that we had too much stuff and that we needed to throw everything away. What we had was some small furniture and things we used to shelter ourselves from the wind. These items were useful and practical for us while we lived on the street, but the City arbitrarily deemed them excessive. The few times they tried to take my tent, I had an absolute meltdown. They would take whatever else they could grab from us and put it immediately in the back of their trucks to go to the dump. There was no posted or written notice at any of these sites before they seized and destroyed our property. Nor did they give us enough time to collect our belongings.

Shanna Couper Orona was a firefighter in Sacramento who lost her job because of a disability, and her home in San Francisco because of a divorce. Her story completely contradicts the classic Chronicle portrayal of homeless folks:

My ex-wife was an attorney at a big law firm. We used to live in the Diamond Heights neighborhood of San Francisco for about ten years. After years of struggling with my disability, we had a painful divorce. I lost everything—including my condominium and my car. Without a place to go and with no ability to pursue my profession, I crashed on friends’ couches for months trying to find a place to land. When that became untenable, I used my disability checks to pay for hotels and motels to spend the night. That lasted only for a few weeks. 4. I have been homeless in San Francisco for about five years. Up until fairly recently, I spent much of that time living in a small tent on Erie Street in the Mission District. After that, I became the test case for a pilot program to build tiny homes for homeless people. 1 I saved up enough money to purchase an RV, which I did, where I continue to live now. I have been on every housing list I could think to get on. All this time, and I am still waiting to secure permanent housing.

I have witnessed police harass homeless people over a hundred times in the past several years. While I was living in a tent on Erie Street, I recall at least three times when I was woken up by police in the middle of the night and told I needed to leave. Officers provided me with no notice, and no one was there to offer me any services. On one occasion, an SFPD officer pushed my tent aggressively while I was inside it. When I told him I understood the law—and was not required to move without notice or a service offer—he told me that I had a “smart mouth.” I was not cited or arrested for illegal camping. But for years, I lived with the fear and stress that law enforcement was going to take my tent away. 10. I have regularly heard SFPD officers say some variation of: “You can go to jail or you can leave, but you’re not taking your belongings with you.” They usually scared people The fear SFPD instilled in us was a tactic. If they could get us to leave, DPW crews could come to destroy our stuff. Then they would claim we had abandoned our property by leaving. This was how they avoided bagging and tagging our belongings. Most of the time when we were harassed, we got no notice from SFPD officers or DPW crews, and the Homeless Outreach Team (HOT) was often not present to offer services.

Henrick Delamora once worked for the Department of Public Works before becoming homeless. Delamora was employed as a bouncer at a club while living on the streets.

My property has been taken and destroyed by DPW and the San Francisco Police Department (SFPD) on two occasions. The first time was while I was still working for DPW. In July 2019, I was living under the bridge at Cesar Chavez Street near the on-ramp. I had gone to my shift at work and when I came back later that night, I found that all my belongings were gone. I received no notice before this sweep and I never received any record of my property being taken. Because I worked for DPW, I went to the DPW office to ask about my belongings. I had to wait for hours to get an answer. 4. I ultimately learned that a DPW crew of three or four people were specifically assigned to sweep my area. But they said they did not know where my stuff had been taken. They never found my property.

I am one of those people who goes to work every day and works really hard but just happens to be homeless. I know so many others who do the same. Why is the City destroying our property while we are at work? What do they expect us to do instead? It just feels like the City wants to keep punishing us for being homeless. I would like to see the City held accountable and understand that what they are doing is wrong.

The complaint includes detailed data compiled from city records and from COH logs showing “massive noncompliance,” as Shroff notes, not only with federal law but with the city’s own policies.

The suit seeks an injunction to block the city from

“citing, arresting, stopping, searching, questioning, or otherwise investigating or enforcing—or threatening to investigate or enforce—any ordinance that punishes sleeping, lodging, or camping on public property.”

That injunction, the suit demands, should remain in place until the city has appropriate housing or voluntary shelter for everyone living on the streets.

It also seeks an order preventing the city from “summarily seizing and destroying the personal property of homeless individuals, including momentarily unattended property, and to prohibit the confiscation of unhoused individuals’ personal property except when bagged and tagged in accordance with Defendants’ own written policies.”

The plaintiffs want the court to appoint an outside independent special master to make sure the city follows the law and its own rules.

“We need to be honest about what’s caused homelessness in San Francisco,” Shroff told me. “You can’t say this problem is too hard to solve. There’s a simple answer: Affordable housing.”