San Francisco artist Kija Lucas’s work upends the idea of “value” in art by focusing on the deep meaning and memory we attach to those special objects in our lives—a carved wooden sparrow, a $2 bill, an anime lunchbox, a ’90s mixtape—that help define our sense of self.

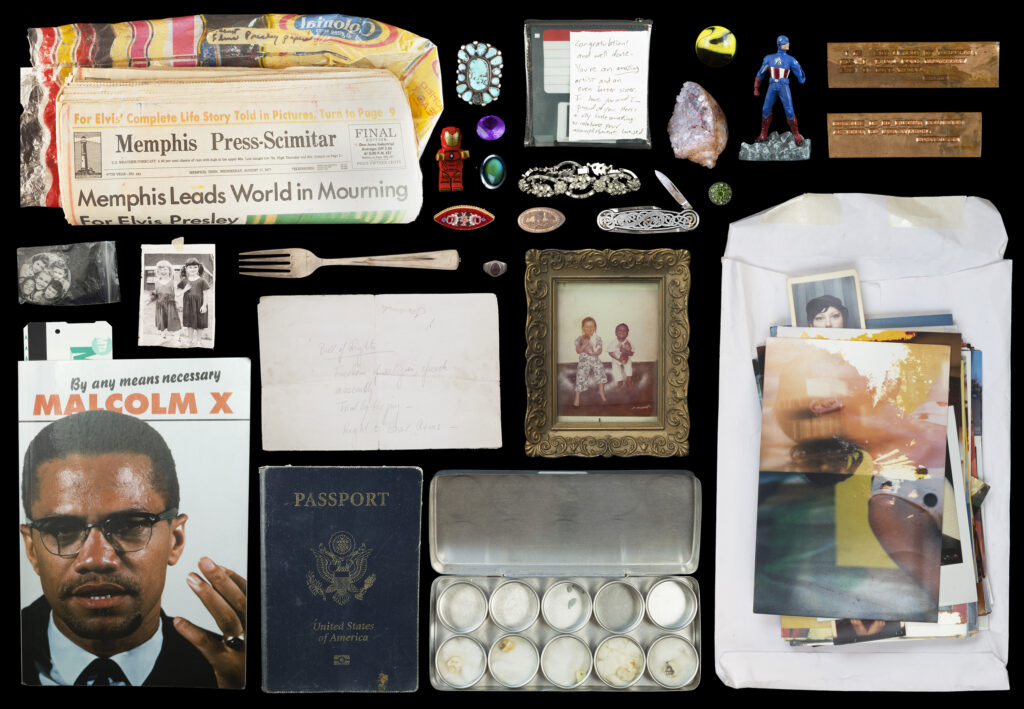

Lucas’s ongoing project, The Museum of Sentimental Taxonomy (formerly Objects to Remember You By: An Index of Sentiment), asks participants to share these intimate artifacts with her, which she then arranges and photographs against a plain black background, as the participants relate the stories attached to each personal totem.

Through this process, which she has developed over several years, Lucas elevates the sentimental, and the occasionally shabby, until we see these humble belongings for what they are: transcendent historical emblems as powerful as an amulet or a sarcophagus. Viewers can’t help but become aware of our own invasive gaze, connecting our own memories to each object while perceiving a sense of loss and nostalgia—should we celebrate, mourn, attempt to stitch it all together, or simply admire?

The urge to find meaning in the mundane has been one of the strongest through-lines connecting art made during this pandemic. And the big players are taking note. On Feb. 19, The New York Times put out an un-bylined call for submissions of a fairly unusual sort, asking readers to send in “photos of objects that remind you of what you personally have lost during this time… A favorite mug, now empty, that a loved one used to sip tea from. A notebook full of scribbles from a dream job that ended in a layoff. A child’s backpack, that never saw the inside of her Kindergarten classroom.”

This forthcoming project, “Share an Object of Remembrance: What Loss Looks Like,” will become a kind of visual response to the first year of COVID—and Lucas was immediately disturbed by its similarity to her own work. On Instagram a few days later, she posted that she hoped to continue her photographic interrogations of keepsakes and what they mean to us “until my old age.”

“I am one artist in a somewhat provincial city,” she wrote, asking fans and followers to alert the Times to the fact that she, a woman of color operating at the margins of the institutionalized art world, has been documenting sentimental objects for seven years. Her mother was among the people to respond, writing a pained (and, frankly, kind of adorable) email to Lori Leibovich, an editor at the Times’ “Well “ section who’s overseeing the project along with art director Jaspal Riyalt.

Leibovich replied that the paper was unaware of Lucas’s work, a fair enough claim, although one that could be remedied with the same Googling a freelance writer does before pitching a story to an outlet.

“Our project was conceived independently and will be part of a larger New York Times health package focusing on grief and loss during the pandemic,” Leibovich replied, in an email Lucas shared with me. “It includes many components: visual essays, journalistic reporting, user-submitted stories and photographs, audio, poetry, and advice from experts to help readers process and manage grief during this difficult time.”

Leibovich went on to note that the Times has undertaken similar projects around the 10th anniversary of 9/11 and this photo spread of items that people who die of COVID leave in hospitals, before closing with a somewhat lofty “Once again, thank you for making us aware of your work. We wish you continued success.”

Lucas calls this exchange “bullshit.” Her real concern, she says, comes not out of pique that they copied her per se, but that people had already begun congratulating her because they thought the Times had taken notice. “I was like, ‘No, no, no, that’s not my work.’ They thought that I was collaborating with the Times, because they saw it and didn’t read it,” Lucas says.

She freely volunteers that a style of photography doesn’t belong to her, and she wants ordinary people to be able to share their stories. “That’s why I make this work,” she says. “But what happens when I propose this work to a space or I propose a grant, and someone’s like, ‘Wait, isn’t this the work The New York Times did?” And that takes away my ability to do my work, because it’s seen as derivative of what this giant media organization did.”

“They should be doing due diligence,” she adds. “I just don’t know what the desired outcome is.”

Sadly, Establishment co-optation of independent art is nothing new. And controversies over who gets credit for coming up with an idea can be as highbrow as the controversy over who should have won the Nobel Prize for Physics for discovering the Big Bang Theory or as lowbrow as debating which is the better bad movie, Armageddon or Deep Impact. I wrote to Leibovich and Riyalt, asking what The New York Times’ policy is when confronted with reasonable proof that an idea they’re pursuing is not an original one. Two days later, I got a thorough reply from Annie Tressler in the company’s corporate communications office.

“The editors at Well were not aware of Kija’s deeply moving work, but are glad to know about it,” Tressler wrote. “However, we believe our project differs greatly from Kija’s—where her work explores sentimentality and memory, ours explores collective grief and loss on a mass scale. Additionally, our project was conceived independently and will be part of a larger New York Times health package on grief and loss during the pandemic.”

Tressler included the same text about prior NYT projects that Leibovich had emailed to Lucas’s mother, before closing with this: “We don’t have a policy on adding names of artists after a project (or, in this case, a callout) has been announced, and since we were not aware of Kija’s project prior to our announcement and believe ours is vastly different—we don’t intend on doing so on this callout.”

In other words, it’s full steam ahead. The ability of a giant media corporation to execute something on a larger scale than a single artist can apparently means two similar things are actually different. Second—and this may be more galling—none of the journalists involved bothered to see if somebody else already had their idea, before leveraging that easily fixable ignorance into a get-out-of-jail-free card to avoid giving proper credit after the fact.

In the meantime, Lucas is going to continue with The Museum of Sentimental Taxonomy in a socially distant way. The current iteration is up at the California Institute for Integral Studies (CIIS), which may be reopening soon. People have begun dropping objects off at her house and tooling around the neighborhood for an hour while she photographs them. She then discusses everything with them outside on the sidewalk, and they fill out a form online. Six feet apart or not, it’s about the intimate, one-on-one connection.

“I prefer to photograph the work myself because I can talk to people about their objects,” Lucas says. “They can have me put in certain information, but I’m listening to their stories while I’m doing the intake, and I’m really interested in finding out what their story is. Those are histories that I wouldn’t necessarily learn otherwise.”

It sounds to me like the New York Times had a much better idea. The “artist” was just taking any object, but the NYT was focused on the pandemic, which seems like a big improvement to me. Besides which, I don’t think you can, or should, protect vague ideas like “collect images with stories”. You would snuff out all innovation, if the first person to do this could block everyone else, and the fact that the NYT has a superior riff on the idea shows the danger of this kind of “protection”.

The 9/11 Tribute Museum features objects recovered from Ground Zero and the stories associated with them. It could easily be described as “Objects to Remember You By”. It predates the Lucas project by years; you can google it. Interestingly, one of their prominent objects is a $2 bill – also featured prominently in the Lucas photograph. (Not that either project is particularly original.)