By Tim Redmond

It’s not, by San Francisco development standards, a terribly big project. It’s not in the Mission or Soma, ground zero for development battles these days.

The Planning Commission chambers Sept. 4 weren’t packed by supporters and opponents. The hearing, tucked deep in a meeting that lasted more than eight hours, was relatively short.

But the commission was sharply divided over the proposal, for the construction of six large residential units at 395 26th Avenue, in the outer Richmond – and the 4-3 vote in favor was directly in defiance of city policy and the mayor’s directive regarding the preservation of existing rent-controlled housing.

It was a remarkable statement of priorities, based on what project opponents called misleading information from the developer, and showed how the Planning Department and the commissioners who oversee it are willing to ignore very clear rules to satisfy the needs of a profit-driven builder.

As one commissioner noted, it set a terrible precedent that could have dangerous implications citywide.

Gabriel Ng & Architechs Inc. wants to build two new structures on the large corner lot at 26th and Clement. Each building would have three units, with three-bedrooms each. The project sponsor argued that there’s a need for family housing in the city, and that six new units, which most likely would be sold as condos, would help the crisis.

But to make room for one of the buildings, the project calls for the demolition of an existing apartment building with two smaller rent-controlled units. And that’s something the city isn’t supposed to allow.

In fact, when the mayor with great fanfare issued his housing directive in 2013, he made it clear that demolishing existing rental housing should only be allowed in unusual circumstances, “with special attention paid to preserving existing rental stock.”

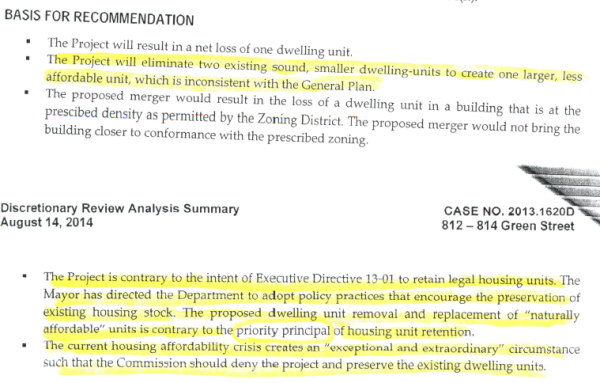

In the past year, the Planning Department has repeatedly refused to approve projects that involve a loss of rental units. In July, a proposal to merge two small rental units into one larger apartment was rejected by planning staff because “the mayor has directed the Department to adopt policies which encourage the preservation of existing housing stock.” Same with a case at 812 Green Street; the planners said it wasn’t okay to merge two units into one because preserving existing rental housing under rent control was the city’s highest priority.

The developer’s lawyer, Alice Barkley, argued that the two existing housing units, which have rent-control protection, have been empty for 20 years. If they were rented out, she said, it would be at market rate.

Not so, said one neighbor testifying at the hearing: “There were tenants in that building, and they were paid to move out,” the neighbor said. “They are not imaginary tenants.”

Steve Williams, attorney for some neighbors who opposed the project, told me that the former residents were students from out of town who were “thrilled to be paid to move.”

Whatever: The existing units could be rented at market rate, but would from then on be covered by rent control. And in fact, if the developer wanted to build on the lot, Williams said, the existing building could be preserved and expanded – and the new units added on would be rent controlled.

In his testimony, Williams said that the fact that this project had even gotten to the commission level with a positive recommendation showed “the tone deafness of this department.” San Francisco, he said, is mandated to protect existing affordable housing. Tearing down rent-controlled units for high-priced condos “is not in the policy,” he said.

Commissioner Mike Antonini, who generally supports any kind of development, said the project makes sense because it will add to the net number of units, and bedrooms, in the city. “At some time in the past there were tenants, but recently it’s been owner occupied,” he said – again challenging the suggestion that the units were vacant for 20 years.

Rich Hillis, who like Antonini is an appointee of the mayor, argued that Lee “wants to preserve housing but also to build new housing.”

But Commissioner Kathrin Moore noted that “the demolition of rent-controlled housing is a huge concern, and has to stay dead center in what we talk about. The overall development pattern sets a bad precedent.”

The new condos, she said “are high-end units not affordable at all.”

And that, of course, was the point – if you can get tenants to move out of rent-controlled housing, then call it vacant and demolish it to build condos, in a small corner of the Richmond, then you can do it anywhere. Which is a scary concept.

And, because city law mandating that new condo projects set aside some housing as affordable doesn’t apply to buildings of fewer than ten units, there will be nothing to keep any of the units below the high prices that new housing commands in this city.

Antonini even suggested that the developer might agree to set aside one unit for sale at below-market rate – but that went nowhere.

So after a lot of wrangling and discussion about parking (which was by far the least important issue on the table) the commissioners voted 4-3 to allow the demolition of two rent-controlled housing units.

Voting in favor – and against the mayor’s own stated policy – were all four of the mayoral appointees: Antonini, Hillis, Christine Johnson and Rodney Fong. Voting to save the housing were Moore, Commission President Cindy Wu, and Dennis Richards –all appointees of the Board of Supervisors.

Williams said his clients are considering appealing this approval to the Board of Supervisors – which would make sense. Because if the city has a policy of protecting rent-controlled housing units, somebody beyond a developer-friendly Planning Commission clearly needs to weigh in.