When Orson Welles died in 1985 at age 70—hardly “prematurely,” since given his prodigious appetites (esp. culinary) it was already a miracle he’d survived that long—he’d long been the model of the brilliant artiste abused, misunderstood, and abandoned by the crass commercial film industry. It was an image he’d done nothing to discourage, even if it was only partly true. Certainly he was ahead of his time artistically, had trouble staying within budgetary limits, and seldom stirred much excitement at the box-office.

But he had also lacked the discipline to exploit and flourish within the studio system, as many equally idiosyncratic personalities managed. Some of his most famously “butchered” features (The Magnificent Ambersons, Touch of Evil) wound up that way in large part because he couldn’t be bothered to stick around and fight for his vision during the editorial process. Later, as the Flying Dutchman of enfant terribles, he started without finishing numerous directorial projects that weren’t “thwarted” by outside meanies so much as marooned by his own indifference to the realities of financing and contracts—leaving whatever footage he completed mired in Byzantine legal tangles, some still-unresolved.

Orson Welles was a genius, but also his own worst enemy. Compare the 11 features he formally completed over the course of a half-century with the 40-plus titles (not even counting stage work) Rainer Werner Fassbinder—another “impossible” personality, reckless hedonist, and non-commercial auteur—churned out in less than 15 years. The latter was driven by work. Welles enjoyed leisure (usually on other people’s tab) a little too much.

The result is that in the more than three decades since his demise, we’ve had several “new” Welles films—the fragments of abandoned projects painstakingly pieced together by old friends and latter-day admirers, filled out by narration or other added materials. This week is unusual in that it brings not just the Holy Grail of such films, but also a much-praised, splendid documentary about its tortured road to the public eye at last.

Simultaneous with its Netflix launch on Friday, the Roxie is hosting a short run of The Other Side of the Wind, a movie Welles shot more of than any other uncompleted feature. And Thursday night, SFFilm’s Doc Stories kicks off its four-day program at the Castro with They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead, a “making-of” that some have claimed is even more fascinating than Wind itself.

When he started filming Wind in 1970—an activity that continued on and off till ’76, with editing efforts stretching into the early 80s—Welles was back in Hollywood for the first time in years. This ostensible “comeback” drew on his enduring affiliations with many old colleagues (the cast includes Mercedes McCambridge, Edmond O’Brien, Lilli Palmer, and other fabled veterans), as well as worshipful new acolytes like Peter Bogdanovich. The latter was then the industry’s hottest director (he’d just released The Last Picture Show) and a patient fan/friend/host who endured notorious moocher Welles as a houseguest for years on end.

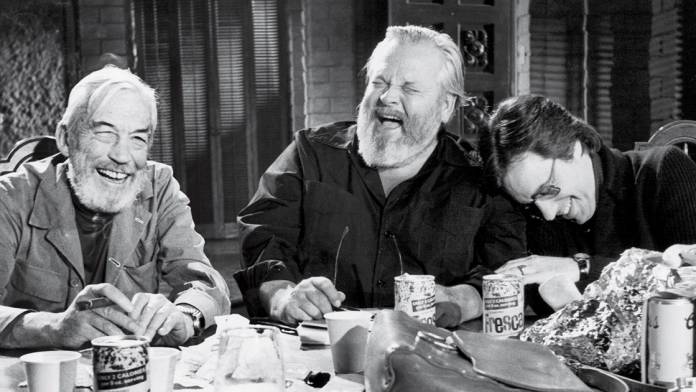

The film would comment acidly on his own mythology by casting fellow director John Huston as boozy, cantankerous veteran auteur “Jake Hannaford,” beset by adoring acolytes (the main one played by Bogdanovich himself), but also picked apart by skeptics (Susan Strasberg plays a pushy critic) and distrusted by the money-men.

Much of the two-hour Wind takes place at a Hollywood Hills party “celebrating” Hannaford’s new movie—but we gradually realize it’s also a forum for him to court financiers, because that project is in dire trouble. Meanwhile, we also see chunks of that film-within-the-film (also called The Other Side of the Wind), a semi-parody of “New Hollywood” and European arthouse trends that’s equal parts Zabriskie Point and Russ Meyer.

In it, a longhaired, motorcycle-riding pretty boy (forgotten ’60s TV actor Robert Ransom) is magnetized by a mysterious beauty (stonily “exotic” Oja Kodar, Welles’ offscreen companion in later years). He pursues her to a hippie club, then has sex with her in a speeding car—two wordless scenes of gorgeous vintage psychedelia. Then they spend a great deal of time artfully nude amidst desert landscapes, Kodar bearing her bareness with all the kitsch pomposity of an Yma Sumac aria.

Self-reflexively hip with its cineaste in-jokes, pseudo-documentary aspects, and “medium is the message” structural games (including its being shot in several different formats and aspect ratios), Wind was very much of its time. There were a lot of such movies as the ’60s turned into the ’70s: I Am Curious (Yellow), Medium Cool, David Holzman’s Diary, The Last Movie, Alex in Wonderland, Cover Me Babe, et al, to name just a few (in descending order of popularity and acclaim).

If Welles had actually released the film when he finally stopped shooting in 1976, it would already seemed outdated—at that point nobody was making, funding, or even bothering to parody pretentious art movies in America anymore. (The Bicentennial Year’s biggest hit was Smokey and the Bandit, with the prior year belonging to Jaws and the next one to Star Wars.) Seen now, in the form that Bogdanovich and numerous collaborators have assembled from the mountain of footage and notes Welles left behind, it regains some of its intended avant-garde (as well as satirical) edge.

20 Feet from Stardom and Won’t You Be My Neighbor? director Morgan Neville’s documentary They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead chronicles a production as messy as everything else about its mastermind’s life at that time. Kodar, Bogdanovich, and others comment on a film that, like Welles himself, was ambitious, out-of-control, and kept changing creative focus. While Kodar’s reminiscences of her late lover are fond, Bogdanovich’s then-girlfriend Cybill Shepherd shares some sadder insights into the floating circus Welles’ life had become, even as it settled for a long spell under the mansion roof she then shared with Peter B. It’s the doc’s final judgment that a clusterfuck of climactic indignities—from bodies as distant as the American Film Institute, the Shah of Iran, and the French legal system—delivered slow death blows to both Welles and his Wind. But at least a couple witnesses here wonder if he ever meant to finish it

Was The Other Side of the Wind worth the wait? Of course. Is it the movie Orson intended to make? Probably close enough, though we can never really know. Is it a ‘good movie’? Umm… let’s just say it’s a curio no true film fan would want to miss, and one that may only be “complete” when taken as one half of a package with the explanatory addendum They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead.

Other films screening at Doc Stories include films about technology (Maxim Pozdorovkin’s bemused yet worrying The Truth About Killer Robots), fanaticism (Talal Derki’s Al-Qaeda-related Of Fathers and Sons), roller rinks (United Skates), and the persistence of modern slavery (Ghost Fleet). Features of particular local interest are General Magic (about a pioneering if ultimately failed Silicon Valley startup), Dan Krauss’ AIDS epidemic flashback 5B, and Clancy McCarty’s self-explanatory Giving Birth in America: California. There will also be shorts programs, and a Friday keynote address by Netflix VP Lisa Nishamura, who’s been the driving force between many of that platform’s well-regarded nonfiction works.

The Other Side of the Wind

Fri/2-Sun/4, Roxie, SF.

More info here

Doc Stories

Thurs/1-Sun/4, Castro Theatre and SFMOMA.

More info here