ONSTAGE Isn’t trampling other people exhausting work? The vein on your forehead bulges from the strain of being greedy.

This is the question that Shen Te, a prostitute with a heart of gold, poses when confronting evil in Bertold Brecht’s The Good Person of Szechwan (at Cal Shakes through July 21).

But she has also shown us how exhausting it is to be good.

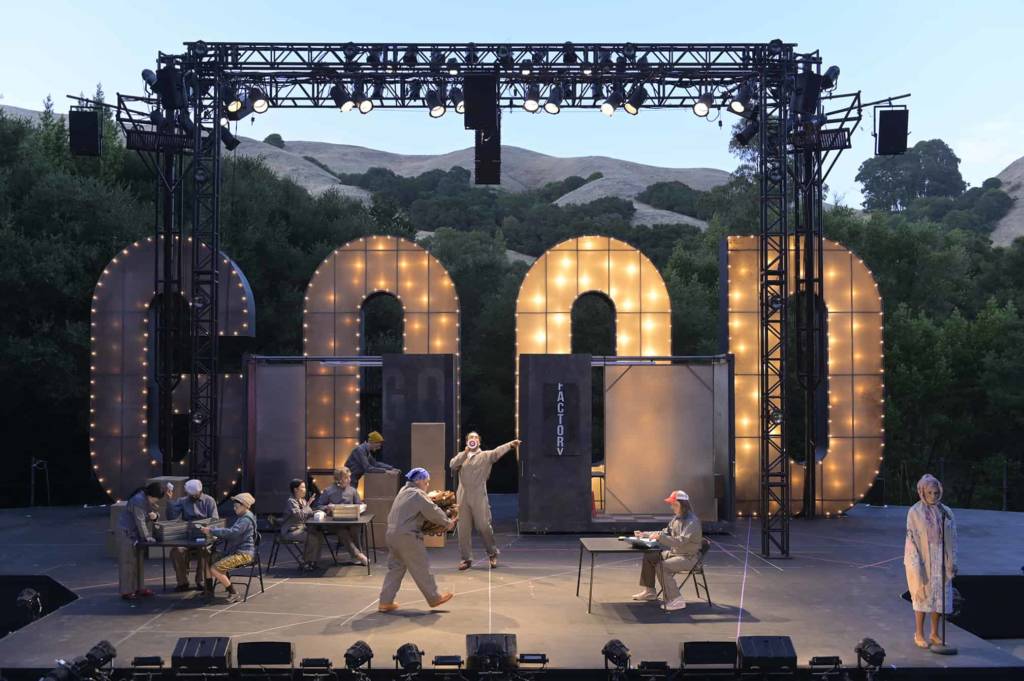

“What does it mean to be a good person?” is the central question of this play. If you have any doubts about that, the backdrop of Michael Locher’s set, will dispel them: Huge letters outlined in electric lights spell “G-O-O-D.” At key moments, the lights blink, sometimes they flash, sometimes they go dark, leaving us with “O” or “G-O-D.”

The question is as timely now as it was when Brecht first wrote the play, as an exile from Nazi Germany.

This is the first time that a Brecht play has been produced at Cal Shakes, and if Brecht was bold to write it in 1943, Artistic Director Eric Ting is equally as bold in putting it on a 21st Century stage, which is not always welcoming to agit-prop theater.

Yet after seven decades, Brecht’s play, translated by Wendy Arons and adapted by Tony Kushner, is surprising, at times uproarious, and always riveting, even as the underlying question nags at your conscience.

The play opens with Wang the water-seller (Lance Gardner) frantically seeking lodging for a trio of gods (Phil Wong, Lily Tung Crystal and Monica Ho) who have traveled to a remote, poverty-stricken town in the province of Szechwan. Wang knows they are gods because “They’re well-fed, they don’t look like they do any work, and their shoes are dusty which means they come from far away.” All the residents ignore or refuse his plea, except for the indigent but generous Shen Te (the versatile and engaging Francesca Fernandez McKenzie). She even forfeits a paying customer so the gods can sleep in her tumble-down shack on the edge of town.

The gods reward her goodness with a sack of silver dollars—but instead of ending her troubles, their money catapults her into a sea of new ones. She purchases a tobacco shop, and is soon besieged by those who demand she share her good fortune: creditors, former landlords, and freeloaders of all sorts, with huge families in tow.

Dubbed the “Angel of the Outskirts,” Shen Te tries to provide for them all, but the destitute conditions of the town impose a harsh reality. Her funds run out and her little space is jammed. No matter how good she is, she cannot overcome the demands of the world around her. “How can I stay good when everything is so expensive,” she laments. “The little life raft is instantly pulled under. Too many drowning people, greedy, grab hold.”

As she struggles to be good, she falls in love with an out-of-work pilot, Yang Sun (Armando McClain) and Shu Fu, a wealthy, well-fed barber (a perfectly pompous Phil Wong) falls in love with her.

Shen Te attempts to solve her dilemma by impersonating her stern cousin Shui Ta, who is as heartless as Shen Te is kind. His way of offering the poor and hungry a better life is to force them into backbreaking work in his factory.

Ting has assembled a star-studded creative team. The cast includes Bay Area favorites playing multiple roles: Margo Hall is both a compassionate neighbor and the manipulative mother of the pilot, Dean Linnard is hilarious as the earnest but bumbling policeman, and J Jha moves easily between roles as a bossy neighborhood busybody and an addled grandfather.

Other versatile cast members include Anthony Fusco, Sharon Shao, Victor Talmadge, and Lily Tung Crystal, the founding director of the Lotus Theatre Company. They all sing and dance, and many play instruments as well.

The original score by Min Kahng uses both Chinese and Western instruments, and the musical numbers range from hip-hop to heroic anthems where dancers strike frozen revolutionary poses, reminiscent of Chinese opera during the Mao period.

As dramaturge Phiippa Kelly explained in a pre-performance talk (talks are held each night and are well worth attending), Brecht, although he had never been to China, was influenced by the style of Peking Opera.

The innovative playwright was drawn to the way that characters directly addressed the audience, not via soliloquy as in Shakespeare, but by facing them and posing difficult questions. And though he was in exile in Hollywood when he wrote this play, Brecht’s style was in stark contrast to the naturalism of American theater of the time—think O’Neill, Miller and Williams.

Using stylized gestures, dance, and mime, Brecht wanted to arrest the audience’s attention. One especially moving scene is all in mime, as Shen Te imagines the child she is carrying as a young boy playing in the field, picking cherries, and hiding from the police. Particularly poignant lines or aphorisms, are marked with a gong.

Brecht is known as the inspiration for American agit-prop theater—from El Teatro Campesino to the San Francisco Mime Troupe—and this production shows why. As Ting notes, “In Kushner’s extraordinary hands, Brecht’s exploration of human decency becomes something delightful, something contemporary, something deeply searching and deeply human.”

Though neither Brecht nor Ting provide the definitive answer of what it takes to be a “good” person in troubled times, their work answers the question what it takes to be a gutsy one.

THE GOOD PERSON OF SZECHWAN

Through July 21

Cal Shakes, Orinda

Tickets and more info here.