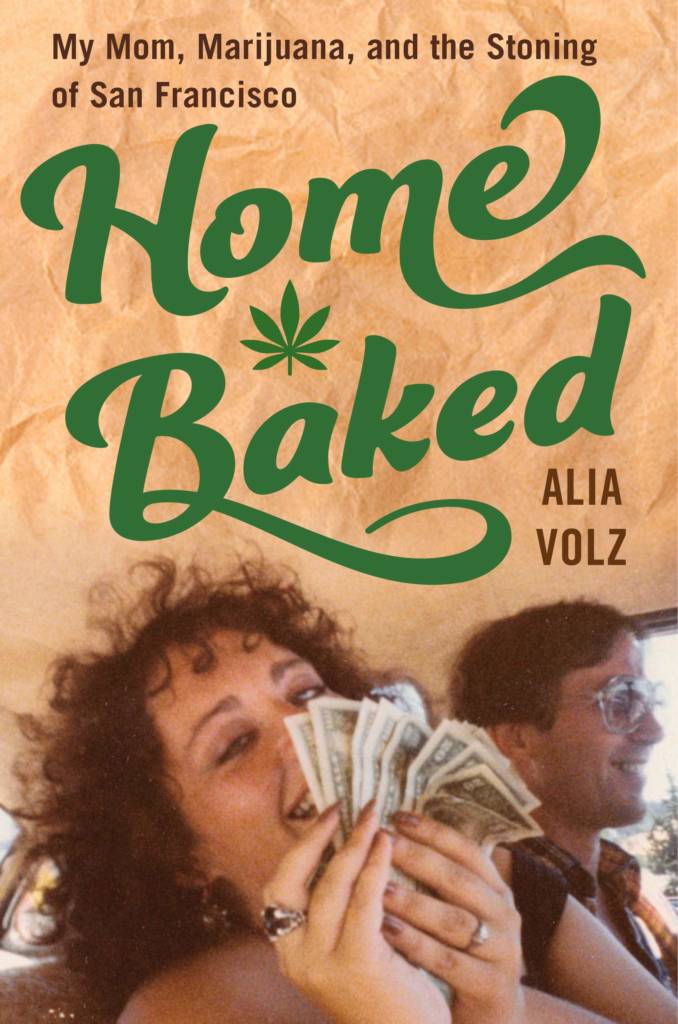

Alia Volz, the author of Home Baked: My Mom, Marijuana, and the Stoning of San Francisco, knew she had a good story on her hands.

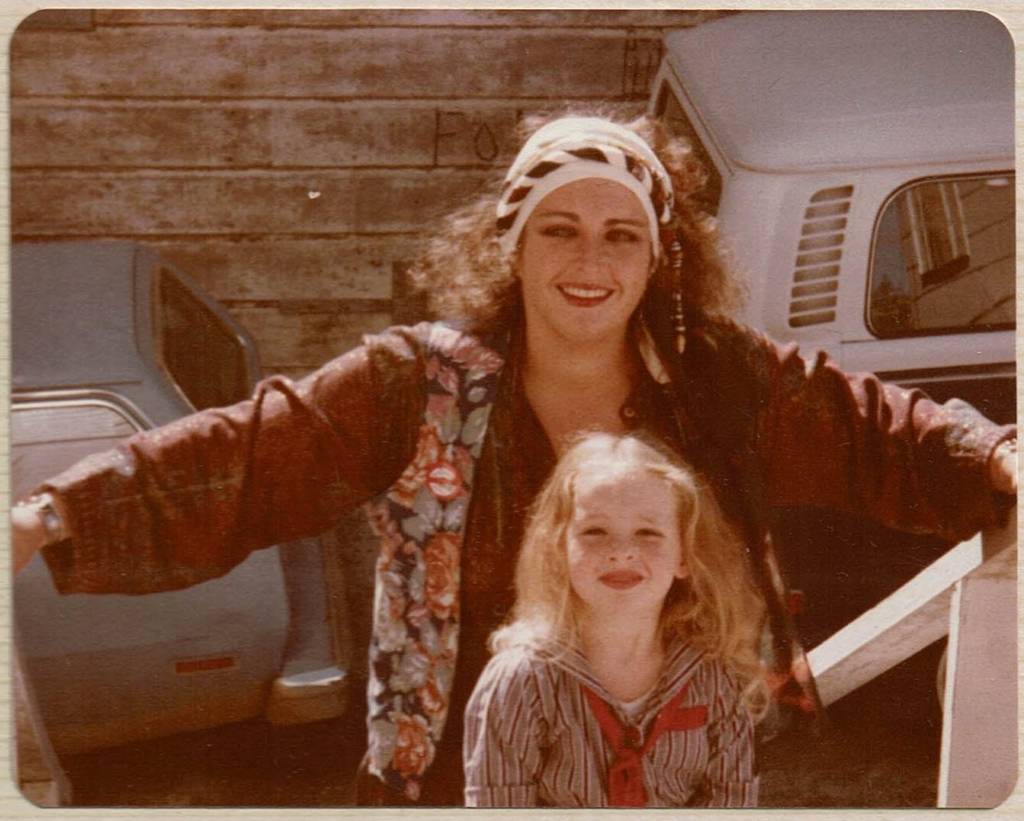

Every time the San Francisco native told anybody about her upbringing as the daughter of Meridy and Doug Volz, the heads of the City’s largest “edibles” bakery in the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, delivering over 10 thousand extra-strength brownies a month to locals, their eyes would grow to the size of saucers as they hung on her every word. People found it astounding that she grew up the way that she did.

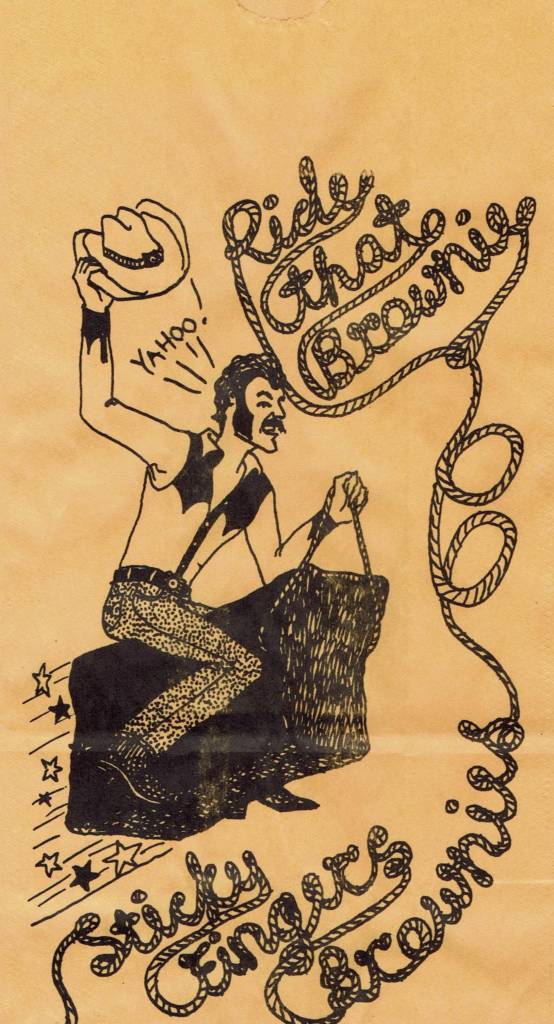

But when the self-described “reluctant memoir writer” decided, 12 years ago, to put her story in print, she quickly realized through her research that it was even stronger and more potent than her eccentric parents or their wildly successful business. Dubbed Sticky Fingers, her parents’ brownie company famously brought relief to countless AIDS sufferers decades before apps like Eaze made weed deliveries commonplace.

So instead of writing a simple family history, she broadened her project’s scope to include the stories of legendary figures like Supervisor Harvey Milk, activist Cleve Jones, and superstar singer Sylvester, who collectively fought to make the City vibrant, colorful, and inclusive before it was crippled by the Jonestown Massacre, Milk’s assassination, AIDS, and the Loma Prieta earthquake.

I spoke to Volz about writing Home Baked, which fittingly comes out on 4/20 with a brownie bake-in, about the most challenging chapters, why weed has never been her drug of choice, and the lessons from the AIDS era that can be applied to the current COVID-19 pandemic.

48 HILLS Why did you decide to write a book about your family’s experience in the budding pot industry in the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s?

ALIA VOLZ I started the book 12 years ago when I started recording the interviews for the book. I only had a vague notion of what it would be. I knew that we had a great story, but I hadn’t really found the heart of it.

The heart of the story came to me in 2016 during the lead-up to Proposition 64, which legalized the adult use of cannabis in California. I noticed that in the conversations and debates around that legislation that there was almost no mention of HIV/AIDS. But I thought that was what drove it.

So it felt like an erasure of a piece of history that I found incredibly important, poignant, and instructive, as far as how to survive or build a grassroots movement when you’re faced with an impossible situation. So that became the impetus to reframe the book and this is why it has to happen now.

48 HILLS The story seems to be as much about San Francisco in its much written about gay golden age in the ‘70s as it is about your family’s own experience in the edibles industry.

ALIA VOLZ Yes, the pieces of my hometown that meant so much to me were just disappearing and being edged out. So it was the desire to tell these forgotten stories about my city in the ‘70s and ‘80s that drove me to write the book.

48 HILLS Was your mother on board with your book idea from the get-go?

ALIA VOLZ She was. My mom isn’t exactly a shy retiring flower and is a bit of a stage hog by nature and does indulge in some self-mythologizing, but I think she never saw herself as a pioneer because she was just making decisions according to her own sense of right and wrong, hippie oracles, and what seemed fun. So on a day-to-day basis, she was just living her life in a way that she found exciting.

So it really wasn’t until I presented the story to her in the way that I contextualized it with my research that she started to think, “Oh well, maybe I did do something that mattered.” I think she’s still trying to wrap her head around it.

48 HILLS Was part of the impetus for writing the book to give your mother some long-overdue credit?

ALIA VOLZ That may have emerged later for me. But I didn’t understand how much my mom was a pioneer in that world until I really dug into the history of the medical marijuana movement and saw where she fit in.

I tried for years to find a business of that size or scope that came earlier and just couldn’t. The more I understood about the historical context, the evolution of medical marijuana, and the evolution of San Francisco culture and politics, I saw that her piece of the puzzle was connected to more elements than I ever imagined.

I would have been happy just to tell a quirky family story, but I found something much richer and more interesting. Then it started to matter to me and became part of my mission plan. It was a nice surprise as a writer to realize that the story you were telling is more consequential than you thought.

48 HILLS You describe several painful chapters in the City’s history between the Jonestown Massacre, Harvey Milk’s assassination, the AIDS era, and the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. How challenging was it to write about these monumental events?

ALIA VOLZ Two of the most difficult parts were the Jonestown Massacre and Harvey Milk’s assassination, because how do you do justice to something like that? How do you write about it in a way that captures the intensity and horror without glorifying it and bringing something new to the conversation when it’s a topic that’s been written about so often? So that was emotionally hard and technically challenging as a writer.

The hardest part, though, was researching and writing about the beginning of the AIDS crisis. It was devastating for me. I spent maybe three weeks where the only thing I did was go through the Bay Area Reporter obituaries and track various threads of names to try to find survivors who were also Sticky Fingers customers to talk to and it was just crushing to discover how many people died.

Then there was a breakthrough where going through obituaries, I found Dan Clowry [a regular client of Meridy Volz’s who worked at Castro’s Village Deli] who connected me to other people and it just opened up. But those weeks combing the beach for survivors were incredibly sad.

48 HILLS One of the City’s most renowned artists to die of AIDS was Sylvester, who happened to be a regular customer of your mom’s. What are your memories of him?

ALIA VOLZ When I was a kid, I would go with my mom to his house in Twin Peaks, which was three stories and all outfitted with this boudoir vibe with lots of velvet, beads, and erotic art on the wall. But I have this clear image of him, always in a caftan or lounging pajamas, a turban, and a lot of jewelry, draped on a fainting couch and smoking a joint with my mom.

As a kid, I had a strong affinity with Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, so I had this association in my mind of Sylvester as the caterpillar smoking his hookah. He seemed magical to me, which is not entirely uncommon. He was just so charismatic.

48 HILLS What was your first experience with Sticky Fingers brownies?

ALIA VOLZ It’s a little hard for me to answer that question because when you grow up in a weed family, it’s sort of everywhere. But it’s not like I was getting high as a kid. I grew up with the idea of pot being the purview of grown-ups, the way the evening news is. You wouldn’t want it.

I’m sure I snuck some crumbs because they tasted good…it was just so casual. That’s part of why I never got into it as an adult. It doesn’t have any mystique. It’s just not that interesting to me or a right of passage for me. In some form, it was always there. For some people, it’s a step toward adulthood or rebellion, but it wasn’t that for me.

48 HILLS Are there lessons that readers can take from your book, particularly from the passages about the AIDS era that can be applied to the current COVID-19 pandemic?

ALIA VOLZ I think what is instructive about it and what we’re seeing play out again is that state leaders, local leaders, and individuals have to organize on a grassroots level to face the pandemic in the absence of governmental action because the federal government is clearly letting us down as the Reagan administration did during the AIDS era.

But I have civic pride that San Francisco has been a leader in taking it seriously and taking drastic action, which also happened during the AIDS crisis. I’m glad to see we can still pull it together.