Bay Areans desperate to go out and get some culture after a year’s hibernation have already made a hit of Immersive Van Gogh, which isn’t exactly a live performance, but nonetheless something you actually have to experience in its own space. (Rather than, you know, on a screen at home.) It’s a 360-degree audiovisual environ housed in a large room on the 2nd floor of the former automotive dealership at Market & Van Ness now known as SVN West.

Created by Massimiliano Siccardi, the 35-minute program (you can stay to take it in more than once if you like) surrounds patrons with a purported half-million square feet of projections that utilize motion graphics, animation and other elements to make Van Gogh’s canvases “come to life” as landscapes, tableaux, and occasional human activity. (As when the convicts in his 1890 “Prisoners Exercising” seem to be doing just that in their depressing little jail yard.)

With attendance limited and social distancing encouraged for the sake of COVID, masked visitors walk around the showroom (there are scattered benches) or mount a viewing platform in its center. Luca Longobardi’s soundtrack runs a gamut from classical themes to Thom Yorke and, at one rather flummoxing point, the diva brass of Edith Piaf warbling “Je ne regrette rien.” There are poetical effects, as when the artist’s simple daubs representing crows “take flight,” or water reflecting a village’s lights ripple beneath the moon.

Some bits are a tad tackier, and one imagines Immersive Van Gogh would attract a bit of scorn if it were staged in a major museum rather than toured as a commercial attraction. Still, it’s a pleasant divertissement, and who can complain about briefly being surrounded by radiance of Van Gogh’s sunflowers, or individual elements of his “Starry Night”?

It’s debatable whether Immersive Van Gogh will actually teach you anything about the artist, though it may well whet the appetite to learn more. For those who’d like to go in prepared, or investigate further afterward, there are no lack of resources: Short and sad in some ways as his life was, in death he’s become one of the most-analyzed and portrayed artists ever. (Little more than a decade after his death in 1890 at just 37, international exhibitions began to win him fast-escalating renown.)

That attention has extended to numerous film portraits, several of them highly regarded. We’ve provided a short guide to the best and best-known such below. For a very late-20th-century art fix, it’s also worth noting the current release—including to the Roxie and Elmwood’s virtual cinemas—of Wojarnowicz: F**k You F*ggot F**ker. Chris McKim’s striking documentary provides a biographical overview the NYC multimedia artist who raged against the institutionalized homophobia that abetted his death from AIDS in 1992–a century after Van Gogh’s premature demise, at exactly the same age.

Meanwhile BAMPFA’s streaming program is celebrating former in-house video curator Steve Seid’s new book Media Burn: Ant Farm and the Making of an Image by showing a couple short vintage films about that SF-based collective’s fabled 1970s conceptual performance art works. Seid will provide an illustrated online lecture on the topic Thurs/1 at 7 pm; the rest of the program is already available, and will continue to be through April 30 (more info here).

The following Van Gogh movies are all available through various streaming platforms, library systems, and so forth. Ticket and general info for Immersive Van Gogh, which is currently running through Sept. 6, can be had by visiting www.vangoghsf.com.

Lust for Life (1956)

Still probably most famous of the biopics, this passion project for director Vincente Minnelli (until then best known for his stylish MGM musicals like Meet Me in St. Louis and An American in Paris) was not a commercial success at the time, but for years remained many people’s idea of Hollywood artistry at its apex. It remains handsome and plushly produced. In many respects, however, this adaptation of Irving Stone’s bestselling biographical novel about Van Gogh (he also wrote The Agony and the Ecstasy, about Michelangelo) hasn’t aged all that well.

Its melodramatic tone signaled immediately by Miklos Rozsa’s florid score, the film at first seems to be canonizing a saint, as there’s heavy emphasis on the protagonist being too…well, virtuous to succeed as a clergyman. Upon discovering painting, he continues to be too pure a seeker for conformist society, because he just can’t stop feeling! and telling the truth! and dressing poorly!

In star Kirk Douglas’ overenthusiastic performance, Vincent’s “struggling with himself” is practically a solo wrestling match—he’s so robust, we’re almost surprised he doesn’t constantly stab the paintbrush right through the canvas. Once Anthony Quinn shows up as Gauguin, the yelling and brawling reach critical mass, triggering full-on mad scenes. It’s a noble effort, but one that now seems constrained by Hollywood convention, and is too eager to embrace “tortured artist” cliches at their most histrionic.

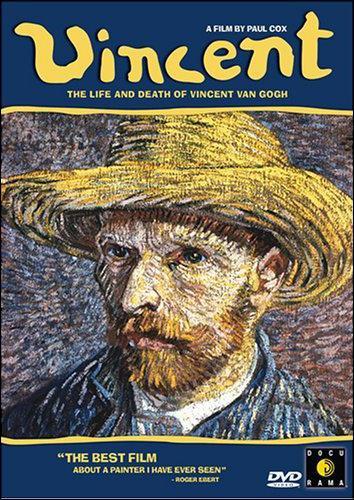

Vincent: The Life and Death of Vincent Van Gogh (1987)

There have been numerous documentaries about Van Gogh (including by Alain Resnais and Mai Zetterling), but Dutch-born, Australia-based director Paul Cox’s film is the one people remember. With John Hurt reading the subject’s own words (he wrote voluminously to brother Theo), it tries to inhabit his mind during the last eight years before his suicide.

Cox’s humane simplicity of approach is particularly rewarding here, as he incorporates location shooting, some staged sequences, and many paintings into a seamless sort of posthumous audiovisual autobiography for his subject. Vincent was a surprise sleeper hit that greatly benefitted SF’s own Roxie Releasing, running for years on the arthouse and repertory circuit.

Vincent & Theo (1990)

Perhaps partly spurred by that documentary, there was a spate of Van Gogh-themed films in the early ’90s, including a Canadian children’s film (Vincent and Me) and a rather silly fantasy segment in Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams. But there’s nothing silly or childish about this highly atypical Robert Altman film, which features Tim Roth as the artist and Paul Rhys as his loyal art-dealer brother. Focusing (again) on their last years—illness claimed Theo’s life soon after Vincent’s suicide—this is a very poignant portrait of a stubborn, loving if also sometimes stormy fraternal bond, with the younger, more conventional sibling often having to play caretaker to his hapless elder. It also digs strikingly deep into the period, and the art itself, conveying the poverty and hardship of the artist’s life while also exalting in the beauty he found in surrounding landscapes.

Written by Julian Mitchell of the play (and film) Another Country, Vincent & Theo was initially made as a four-hour European TV miniseries, then released to theaters in much shorter (but still methodically paced) form. The usual stylistic signatures familiar from such Altman joints as M*A*S*H, Nashville and The Player are absent here; some of his fans thought this “too Masterpiece Theater” as a result. But it’s actually one of his best films—perhaps in part because it steps so far outside his standard mode—as well as arguably the best film dramatization of Van Gogh to date.

Van Gogh (1991)

Another stubbornly individual director, the former actor Maurice Pialat, made this very, very French take on the artist’s final weeks, when he lived primarily in the village of Auvers-sur-Oise on the farthest outskirts of Paris. Just out of a year-long asylum stay (where he did some of his greatest work, including “The Starry Night”), Vincent moved there in order to rest and be near physician Gachet (played by Gerard Sety), though rather than stay at the latter’s home he took a humble room at the local inn.

Far from being conspicuously angst-ridden, the Van Gogh played by musician Jacques Dutronc is a bit withdrawn and brusque, but not particularly eccentric or antisocial, let alone “mad.” (Among the film’s surprises is his rather busy sex life, between prostitutes and Alexandra London as the doctor’s rebellious daughter.) The film does not take great pains to evoke the paintings in cinematographic terms, though the scenery is attractive enough. To a point, the emphasis is on a principally charming sense of everyday life, pleasantly meandering and a bit arbitrary in dramatic focus.

Yet eventually we do see how Vincent is plagued by self-doubt, his behavior growing more contradictory and difficult. Even then, however, Pialat resists any “big scenes,” avoiding “the ear” entirely, and keeping the fatal gunshot offscreen. Van Gogh may seem borderline perverse in sidestepping most of what we might expect from a film about its subject. But its low-key nature also brings a strong sense of empathy and authenticity, making this nearly three-hour drama something that brings considerable rewards for the patient viewer.

Loving Vincent (2017)

Some may dismiss Immersive Van Gogh as mere eye candy, but there’s nothing terribly wrong with that. An even better example of the same principle, you might argue, is this multinational coproduction conceived by Polish painter Dorota Kobiel. She made a 2008 short of the same title first, then co-directed this feature expansion with Hugh Welchman. The hook is both irresistible and suspicion-rousing: Loving Vincent is a “cartoon,” so to speak, animating a version the artist’s life story in a style slavishly faithful to his canvas style. You might think that would be gimmicky at best, tacky at worst. But the film was made by 125 artists literally painting in oils on 65,000 frames, resulting in something of arresting beauty, and impressive fidelity to Van Gogh’s aesthetic.

The script is considerably less enchanting, trying to create a sort of murder mystery from the fiction of a postman’s son growing obsessed with Van Gogh’s death (as he tries to deliver a posthumous letter). He conducts an amateur “investigation” a year after that event, prompting flashbacks to the artist’s life. None of this is very interesting, or adds much to our insight into the titular figure. But Loving Vincent is so visually rich, even intoxicating, that you can just turn off your brain (and perhaps the soundtrack of voice actors) and experience full sensory overload watching the extraordinary animation craftsmanship at work.

At Eternity’s Gate (2018)

Last and least in the cinematic Van Gogh canon is this effort by fellow painter Julian Schnabel. Actually, casting Willem Dafoe as the tragic-in-life, immortal-in-death Dutch painter was an inspired choice. Despite his accent, the script’s incongruously modern language, and the age difference (the actor was then 25 years older than Van Gogh lived to be), he’s physically apt and summons up the appropriate near-possessed intensity.

Alas, almost nothing else feels right about Schnabel’s feature, which will inevitably remind you that apart from The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, his movies are regarded about as well as his paintings—which is to say, as pretentious luxury items. Working from a screenplay credited to him, domestic partner Louise Kugelberg, and famed veteran scenarist Jean-Claude Carriere, he chronicles Vincent’s last couple years, when the artist painted nearly all his great works but lived in poverty and deteriorating mental/physical health.

Schnabel portrays the latter aspects by the most heavy-handed means possible, repeating entire dialogue exchanges verbatim and partially obscuring the image to convey a perspective “compromised” by illness. Worse, he wildly over-does the already tired stylistic device of jittery hand-held camera work to suggest “immediacy.” Rupert Friend is fine as brother Theo, Oscar Isaac is OK as an unflatteringly depicted Gaugin, and there is no lack of good additional actors wasted in nothing roles (Mads Mikkelsen, Mathieu Amalric, Emmanuelle Seigner, etc.). But this ugly, affected, tedious and exasperating film lets them all down.