Rupy C. Tut didn’t plan on being an artist, although she came from an environment that recognized the importance of the arts.

“I grew up in a family that taught me to see artists as the chosen ones, as individuals who do really important work. This notion makes me live and work with a sense of responsibility, surrender, love, and respect for what I do as a painter,” Tut told 48hills.

Born in the state of Punjab in northwestern India, Tut arrived in Southern California with her family in 1997 at the age of 11. She went on to attend UCLA, where she majored in evolutionary and ecological biology with a minor in South Asian studies (2006), and completed a master’s in global health at Loma Linda University (2009). In 2011, Tut married and moved to the Bay Area with her husband, who was working in tech. Currently, she lives in the Redwood Heights neighborhood of Oakland.

“During my process of applying for public health jobs in the Bay Area, I began a studio practice, which in a few years evolved into receiving traditional art training and building my artistic voice and practice,” Tut said.

Tut strongly believes in the power of storytelling and the discipline it requires. As a grandchild of refugees from the 1947 partition of India, her stories reflect an interest in investigating identity and belonging. Her paintings often express conversations with ancestors.

“These inquiries are layered through my own experience of immigration and my parents’ struggles with place and identity when they moved to the US. I am guided by understanding the complexities of self, of home, and of searching for a place where I can belong as an immigrant, as a woman, as a mother, and as a citizen of this planet,” Tut said.

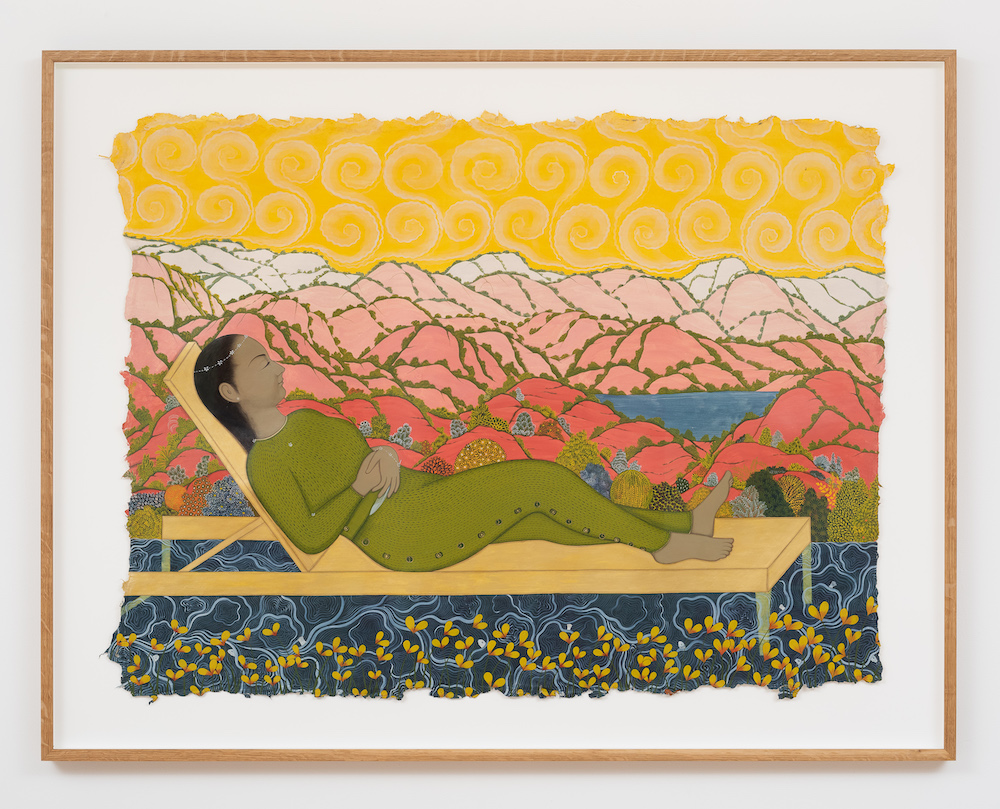

Trained in traditional 18th-century Indian painting, one of Tut’s daily aims in the studio is to innovate within this methodology, which she finds both tedious and historically significant.

“I strive to center the narrative around female characters who are struggling but resilient, facing hardships but also bolstered by support systems, and tackling patriarchal challenges while also setting examples of winning the fight,” she said.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

Tut feels a responsibility to paint these characters, who are not only glimpses of herself and the women she knows, but also the woman and human she aspires to be. Representing them in her works, so that women’s lives and impact on this world are not easily erased, is important to her.

The painter seeks to leave her own impact on the world with every act and every brushstroke, noting the importance of legacy—particularly as a female artist. She strives for excellence in perfecting methodology, while accepting the inherently imperfect nature of art and life. She is also grounded by the realities of being a 9-5 painter and for the rest of the day, a mom changing diapers and tackling tantrums.

Tut’s studio is in a well-lit, third floor attic space in her home. Because the walls are angled, she works mostly on the floor, surrounded by an array of bowls of hand-mixed pigments. She sources the paper, most of the raw material for pigments, and handmade brushes unique to Indian tradition.

Each painting takes an intense journey, unsupported by mechanical or automated processes: a first drawing, transfer from a lined blueprint on butter paper to hemp paper for the final drawing, pigment preparation, the coloring stage, a first round of burnishing, adding details with a two-haired tip brush, and the final burnishing to prepare the work for framing.

“The character and composition are mostly finalized at the blueprint drawing. However, I surrender to the twists and turns that happen at the coloring stage. The notion of allowing the paper to be a character in the decision-making of where the work is headed is also important to me,” she said.

Tut doesn’t chase perfection or a sense of completion, but she does believe there is a point at which the work contains the most accurate version of the story she is trying to tell. Speaking more about her evolution as an artist, she says she began working as a painter to crack some of the silences around family and community trauma associated with displacement.

Further evolution of her work occurred through motherhood. Her central characters became versions of herself, the mothers she was raised by, and the mothers that metaphorically exist in nature and in cultural and literary narratives.

The pandemic further pushed her to look inward, and to sit with her demons regarding patriarchal conditioning, privilege, motherhood, and the revolutionary and necessary act of making art. The marked degree of isolation, the juggling of parenting a toddler, birthing twins, and having long stretches of separation from her work, created an awareness of the unequal burdens placed on women and mothers during the pandemic. She processed her experiences and traumas into paintings for two solo shows last year at the Triton Museum of Art in Santa Clara and Jessica Silverman in San Francisco.

“Through the more difficult days, I witnessed a boiling over of collective frustration and protest against disparities and brutalities put forth in the mainstream by social movements like Black Lives Matter, the efforts against caste discrimination in the US, and response to hate crimes against AAPI community members. As a result, the characters created in my paintings last year are dominated by anger, frustration, isolation, endurance, and determination,” Tut said.

Though her characters are in some degree of danger and threat, they are not helpless. For Tut, they resemble earlier generations of women—but also possess contemporary significance.

“While the characters are imbued in self-reflection, they are not without connection and care for the world they live in eroding due to climatic tragedies and war,” she said.

This year, the narrative has shifted as Tut finds herself seeking a break from the exhaustion of the previous years by turning to hope, to healing through natural surroundings, and to strength through ancestral presence. Thus, in her solo exhibit “Out of Place” at the Institute of Contemporary Art San Francisco (which runs through January 7), Tut investigates our daily attempts at hope, even as they are depleted by the unfolding events locally, nationally, and around the world.

Letting go of the burden of being a voice for stories of struggle, whether personal, familial, or collective, has allowed her a freer exploration of everyday life. Characters interface with metaphorical representations of the world. Landscapes, evoking the deep-rooted emotion of regeneration that we find ever present in nature, become core expressions of the character of home, their changing nature expressing a specific interaction and emotional arc between the female character and place. Tut says the characters in these newer works are not resilient, virtuous, or typically heroic in quite the same way, and rather express those traits through the daily act of survival.

“The visuals depict how a body can interact with the space around them, and how place can establish and express a relationship to a person inhabiting it. Landscape is a way of communicating for the central characters as well as an ancestral presence I am trying to find within my effort to belong more and more to the land I am on,” Tut said.

Tut is also included in the group show “Speculative Fabulations,” which opens in January at the Asian Art Museum and was curated by Naz Cuguoglu. During the same month, two of her new commissioned works will be featured in a group show at the Fowler Museum at UCLA. The Eiterberg Museum in Indianapolis has commissioned and acquired a work for a group show opening in April. Her representation by Jessica Silverman was also recently announced.

Rupy C. Tut wants us to experience the beautiful detailing and the mindful process of her work, as well as its hidden symbolic language. Above all, she hopes personal explorations of her own interior life can somehow connect with viewers’ own experiences—our surroundings and our own memories, yearnings, and relationships.

“Chase truthful making,” Tut said. “Make time to live so you can paint life more closely. Be kind to people and be on time always.”

For more information, visit her website at rupyctut.com and on Instagram.