Pablo Manga began his dynamic exploration of color and geometry by using semi-transparent colored packing tape as his primary medium, a material that he discovered in a moment of a keen awareness.

The artist was born on a futon in the home of his parents—a Colombian immigrant father and Italian American mother—in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He says that his parents’ rebellion against their Catholic upbringings and studies in macrobiotics, a holistic philosophy of food and the natural order of the universe, brought them together in the 1970s. Manga grew up in and around Cambridge and Boston and moved to the Bay Area in the fall of 1991 to go to college.

“When I was deciding between UC Berkeley and UC Santa Cruz, I came out to visit and spent a day on each campus—but about a week falling in love with San Francisco. I ran all around, from North Beach to the Mission to Land’s End, memorably striking up laughter, conversation, and friendship over Dawn Fryling’s giant photographs of toasted bread at the SFMOMA. From there it was ‘sign me up!’” Manga told 48hills.

After college, (B.A., Philosophy, UC Berkeley, 1996) he moved around, returning to the Bay Area in 2000 and making it home ever since. Manga received his JD at UC Berkeley School of Law in 2003 and has lived in Oakland, near Lake Merritt in the Ivy Hill neighborhood, since 2006.

“My partner and I dated briefly in college when I lived downstairs from her on Durant Avenue in Berkeley. Later, in unplanned coincidences, we kept finding ourselves living near each other: in Park Slope, Brooklyn; then kitty-corner from each other at 24th and Mission in San Francisco; later in West Oakland; and then just two blocks away from each other on Sixth Avenue in Ivy Hill. We finally took the hint and got together again. But we still don’t know for sure who was stalking who,” Manga shared.

But how did he arrive to where he is today, creatively speaking? Manga starts by saying that, for better or worse, he is not one of those people who always knew they wanted to be an artist, though he was surrounded by art and examples of it being a part of the big picture of a full and creative life.

Manga illuminates by saying that his grandfather had a basement studio and painted Impressionist-style street scenes and still life works. His father cavorted in the New York art scene of the late 1960s and made several abstract paintings and drawings, including one titled Caribbean Orbit that lived on the wall of his home office as far back as Manga can remember. His mother went back to college at MassArt while he was in elementary school, quilting and weaving on a loom in the family home, and she continues to weave rag rugs today. His stepmother also went to art school. One of her Willem de Kooning-influenced sewn felt pieces hangs in a frame on his wall.

“And so it was that suddenly, after two years of teaching Spanish and bilingual math at a public junior high school in New York City, and casting about for whether to stick or twist, I had a kind of thunderbolt feeling that I wanted to take a year off to make art with more intention than I ever had before,” Manga said.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

He moved into a spare room in a friend’s Mexico City apartment with a copy of A Thousand Plateaus (Deleuze/Guattari), a cast iron skillet, and his mom’s old oil paints. Up until that point, he had mostly worked in collage and found objects.

“I started painting, drawing, taking photos, smoking Delicados, and eating a lot of Tacos Hola. Then one day, coming out of Metro Chapultepec, I was stopped in my tracks by the sight of a street vendor with a small table piled high with rolls of colorful tape like I had never seen before. I bought a dozen rolls and started experimenting and found that the tape bridged my interests as something both painterly and plucked from daily life,” Manga said.

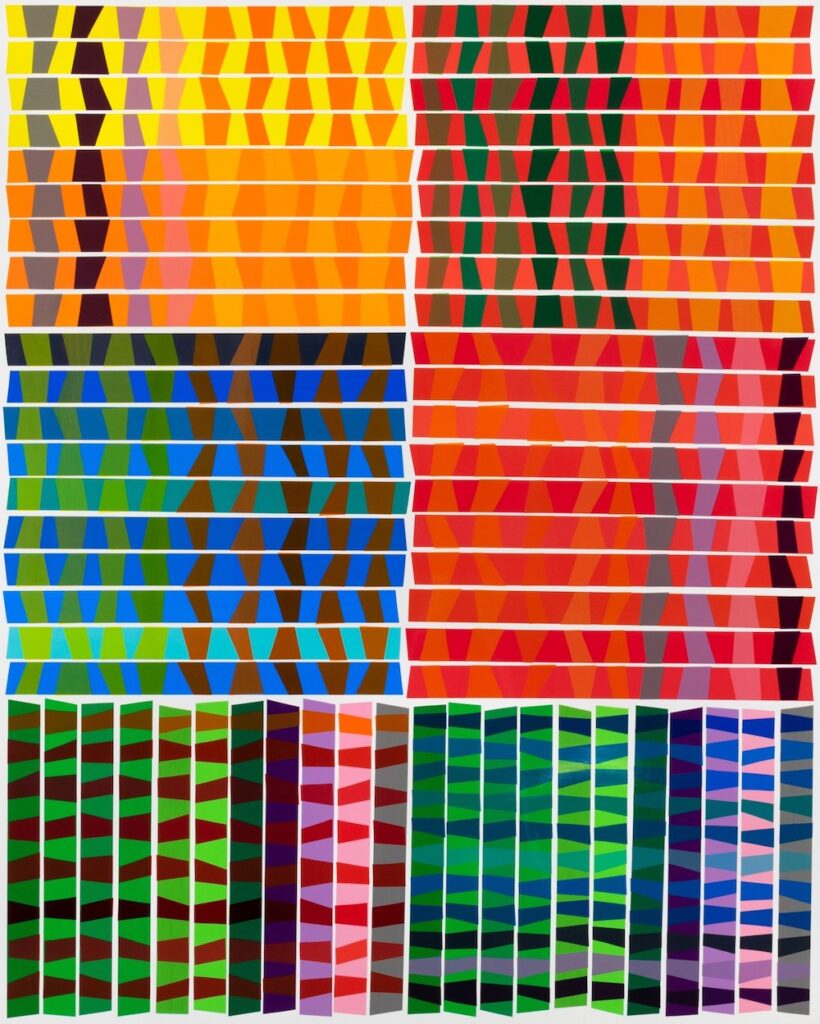

And so began a movement that was oriented towards vivacious color and shape, yet was so much more. The discovery led the artist into a deep and sustained exploration of tape as medium, developing abstract compositions in “layered monochromes, rippling lines, and destabilized grids.” While a burgeoning desire to live as an artist was taking hold after his return to the Bay Area, Manga was simultaneously involved in his career as an arts lawyer in San Francisco and an asylum staff attorney at the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

“I will always be grateful that my partner and I were able to envision and build a transition away from law to full-time artist, art-husband and stepdad, chef and cocktail maker, gardener, house painter, etc.,” he said.

For Manga, being part of the Bay Area art scene hits a sweet spot.

“It’s a vibrant and stimulating community that is large enough that there’s great work to see, including great dance and music, while being approachable and welcoming in ways that foster stimulating conversation and deep friendships. You always see people you know and there are always new people to meet,” he said.

It will come as no surprise that Manga admires the later work of Dutch painter Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), which he feels never gets enough attention. Manga indicates how Mondrian’s paintings were a jumping off point for his own 2011-2012 series Bold as Love aka the Mondrian Acid Test, which includes the piece Reposado.

“I’m also drawn to Agnes Martin and Ellsworth Kelly, two unique artists whose reductive work is incredibly rich and experiential,” Manga said.

Manga says the experience of being in nature is also an ongoing inspiration for his work.

“It connects perception and meditation in an embodied experience of the world, the flux of becoming, and of finding oneself always in the midst of that movement and transformation,” he said.

He tries to get as much as he can of the pleasures of being a body in motion: disorganized pick-up soccer, cycling in the Oakland hills, easygoing tennis, snowboarding in the Sierra, and any opportunity to dance.

In creating “perceptually charged, geometric abstractions” in both acrylics and packing tape, Manga aims to engage us with works that contain more than meets the eye.

“I make compositions that activate the eye and reward sustained viewing with the emergence of shifting patterns and unfolding dynamic relationships of shape and color. I favor irregular quadrilaterals, with angles, dimensions, and distances plotted by eye rather than measured by rulers, and scissor-cut blocks of tape with lines that bend and bow almost imperceptibly, to form loose, destabilized grids that show perception itself to be an ordering process,” Manga said.

Color plays a similar role in his work. Colors appear in unique two-color block combinations that are never repeated within the composition.

“This creates a visual play and slippage of identity and identification. In The Interaction of Color, Josef Albers teaches that ‘color deceives continually’, but I would reframe his point by saying that color reveals an important truth about perception,” Manga said.

He continues to tell of other philosophical influences on his particular approach.

“I’m drawn to the essential openness of abstraction, that these are ‘pictures of nothing’ as Kirk Varnedoe put it, or that ‘what you see is what you see’ in Frank Stella’s famous formulation. At the same time, abstraction is a vessel that can carry meaning. For me, the specificity in these formations is significant of aliveness, multiplicity, and relationality. These ideas are central to my thinking and are embedded in my work,” Manga said.

Manga’s studio is located in the Fruitvale neighborhood of Oakland located a half-hour walk from his home.

“I look out onto the garden from the three large windows of my bright and sunny studio, which is affectionately known as the sugar cube because of its almost 14’ x 14’ x 14’ dimensions. Sometimes a friend will wave to me from the number 40 bus,” he said.

Manga shares his space with artists Evan Holm and Christine Wong Yap (and formerly with Lauren Szabo).

“Between the three of us there’s a good buzz of art-making activity, informal chatter, and sharing of ideas. On top of that we get together for periodic studio visits to dive into each other’s work, and we host artist socials to unwind and connect our extended communities,” Manga said.

Manga prefers working in daylight for clarity of color and detail, so he tries to get an early start with a slow wind-down in the evenings. If possible, he will leave something in progress at a good stopping point so he can return to it fresh and clear in the morning.

“If I’m lucky, I might even still have access to thoughts and images simmering in my mind overnight. As a complement to the daily routine, I like to fold in days when I stay late and just kind of reflect and look around at what’s happening with more of a sense of curiosity, rather than being in the mode of trying to make something happen,” he said.

When Manga is working, music is on. These days, it’s usually sounds like Sun Ra Arkestra’s Living Sky, Vijay Iyer, or Makaya McCraven. If he’s focusing on a packing tape artwork, he assembles his scissors and rolls of tape, working fast and loose on paper.

“Laying down tape and peeling it back up again or moving it around to keep refining a composition, I don’t worry that there are creases in the tape or that the paper becomes scuffed, smudged, or worn. When I think I’ve got something, it’s time to give the composition a good long look to see if it can sustain the scrutiny. If not, I keep making tiny adjustments or wholesale changes,” he said.

This part of the process can take minutes, hours, or days. Manga relates that he felt genuine camaraderie when he read about American installation artist Robert Irwin’s similar approach while working on a series of line pieces, resonating with how his process often involved dozing off and on to fully absorb the perceptual effects of small changes.

“When a composition has the right action and internal dynamics, moving the eye around, flashing one pattern and then another, with patterns running interference over each other, it’s done. Or rather, it’s ready to be begun (again), with full concentration and probably in monkish silence, laying down each piece of tape smooth and flat on a pristine, laboriously sanded and gessoed wood panel—in rhythm with my breath, and making a clean cut by hand with scissors, such that the angles, proportions, layering, reveal, and spacing all have good action,” Manga said.

And if not, he peels it up right away and starts all over again.

The pandemic brought new developments to his practice. He was a parent-artist awardee for a printmaking residency at Kala Art Institute in Berkeley, and volunteered with a group of artists to paint murals on the partition walls of a temporary field hospital in the Presidio, an area set up for overflow care in the event of a surge in Covid hospitalizations.

“Building on these experiences, I have continued engaging questions of scale and materials, bringing the shapes, colors, and compositions of my work in tape into a new body of acrylic paintings,” Manga said.

“The work is an invitation to the viewer to rest in awareness, in the dynamics of perception, to see themself seeing—and feeling-thinking-being,” he continued.

Pablo Manga has worked with Farm Projects on Cape Cod for over 10 years and has had four solo shows with the gallery. Locally, Manga will participate in the annual benefit auctions and 50th anniversary celebrations of Kala Art Institute through April 27 and Southern Exposure from March 30 to April 13. Manga has also shown his work the Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts, and Galería de la Raza. His piece Ojalá was included in the inaugural de Young Open at the de Young Museum and in Root Division’s “MFA NEVER”” exhibit”. He has had several successful shows with Hang Art in San Francisco, but amicably ended his representation by the gallery this year in order to seek new opportunities, saying it was time for new growth.

“Everything’s always changing,” Manga said. “Hopefully, our ways of seeing and perceiving have the capacity to change as well.

For more information, visit his website at pablomanga.com and on Instagram.