In an interview with Phil Matier on CBS April 1, State Sen. Scott Wiener repeated a line I’ve heard from him, and from many others in politics and the news media, over and over:

“There’s a reason we don’t build much housing,” he said, “and it’s been that way for 50 years.”

This is one of the central pieces of the housing market mythology that defines the debate over SB 827 and the larger question of development policy in the city, the region, and the state.

And when you look at the actual facts, it doesn’t seem to hold up.

Here’s how Fernando Marti, co-director of the Council of Community Housing Organizations, puts it:

We have asked reporters to give the source of the assertion that the state has had “50 years of underproduction,” which gets used over and over as though it is fact, and no one has been able to provide a source.

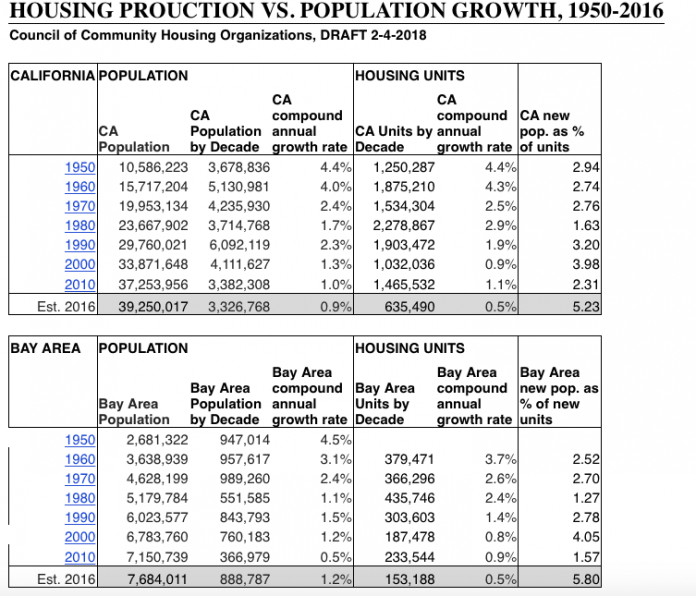

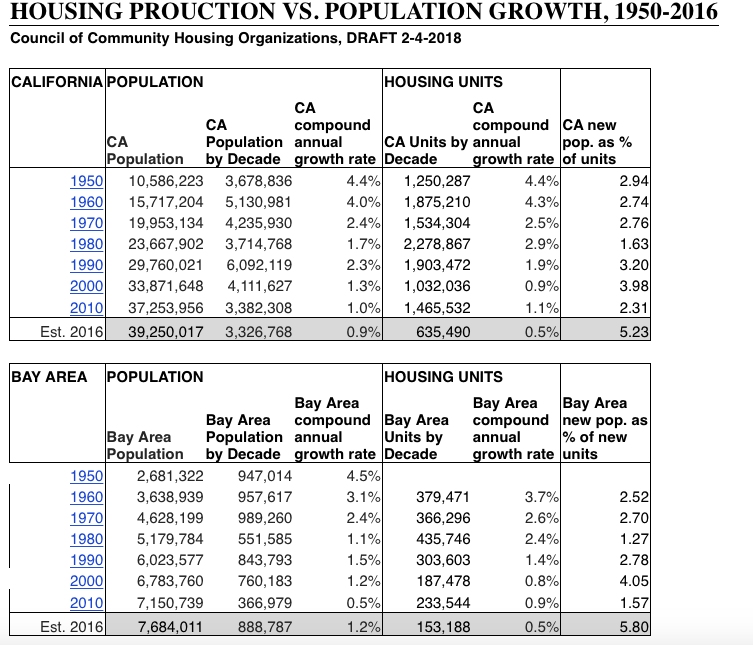

So we looked at the Census data for the Bay Area, going back to 1950, and guess what we found? Construction was booming 50 years ago, and 40 years ago, and 10 years ago. In fact, units were being produced at a much faster rate than population growth throughout the 50s, 60s and 70s, and again in the 2000s until 2008.

Maybe low-density zoning and Nimbys had something to do with slowing production in the 90s, but then again, it could also be that there was a deep recession in 1990. And how can we explain that those factors seemed to suddenly go away during the construction boom of the 2000s? In the Bay Area, housing production was growing at a rate almost twice as high as population growth. And then, did cities suddenly downzone again in 2008? No, it’s something else…

What the data shows is that, while the rate of production generally tracked population growth, often faster, it crashed in 2008, and even with the booming economy, it hasn’t come back. The sooner we start understanding what’s really been happening since 2008, rather than blaming a fictitious “50 years of underproduction,” the sooner we can get to real solutions that matter.

The same holds true for San Francisco. We haven’t had 50 years of underproduction; in fact, the population of the city fell from 1950 to 1980. Much of that may have been suburban flight (mixed with the displacement of urban renewal), and neither of those factors were anything to be cheered. But the city didn’t “underbuild” because of Nimbys or CEQA or anything else.

Census figures should the population of SF peaked in 1950 at 775,000. It fell to 740,000, then 715,000, then 678,000 in the next three decades. It wasn’t until 2000 that the city was back to its 1950-level population.

The opposite was happening in Santa Clara, Marin, and Alameda counties. But in those counties, too, housing production was keeping up with population growth.

Here’s the data, with sources:

Population 1850-2010: US Census

California Housing Units 1970-2010: 2010 Population and Housing Unit Counts, Issued August 2012

California Housing Units 1940: https://www.census.gov/hhes/www/housing/census/historic/units.html

Bay Area Housing Units 1950-1960: http://www.bayareacensus.ca.gov/counties/counties.htm

So it’s not “decades of underbuilding” that we’re facing. It’s a decade or two of extreme, unlimited growth in the tech industry driving tens of thousands of workers, who moved here from somewhere else to take jobs, competing for existing housing.

It would have been almost impossible to build housing fast enough to keep up with that demand. That’s why, in the 1980s and 1990s, the people who are getting blamed for the current housing crisis were demanding that the city limit office growth and link it to new housing construction.

The CEQA battles of the 1980s and 1990s weren’t over housing; they were over office buildings, which created a demand for housing that the market wasn’t going to meet – because back then, there was a higher return for developers in office construction than in housing construction.

We can argue over whether SB 827 will solve the current crisis. But as Wiener is fond of saying, everyone has the right to their own opinion, but they don’t have the right to their own facts.

The hippies you love are the ones who went out and started the tech companies lol

still on with that nonsense? What the city wants is money, therefore they approve huge market rate buildings for the tax money. The twitter tax break was about 1/2 hour of SFgov’s spending, it’s long since recouped the “break” and then some. Against employers providing employee transportation too? Why?

Yes, because there’s a huge amount of pent-up demand – e.g. among people who are currently living with roommates but would rather have their own places; people who have been forced to flee SF but are desperate to move back, etc.

Of course they increase costs. The question is how much. If a developer of 200-unit building ends up having to pay $200,000 for a CEQA report, that adds $1000 per unit, which is dwarfed by the $1m the unit would cost.

Mind you, there are some regulations everyone will want in place, like earthquake-safe construction. The paper does not distinguish between more popular and less popular regulations.

All of those support staff (handlers, lawyers, etc) add to business costs (and risks, in so far as the agencies may do differently from what the support staff expect). Saying that they have lawyers to deal with this doesn’t mean it doesn’t cost money. (!)

Stepping back — from first principles, it seems fairly clear that regulation which decreases the number of units that can be built should increase the costs of both new and existing units; this is basic economics. Do you really mean to argue that increased regulatory restrictions don’t generally increase costs? That position is hard to believe as a serious argument. You can talk about correlation vs causation, but tests with controls are rather difficult for situations like this; what “proof” would you consider convincing?

Saying that increased regulations ensures that externalized costs (infrastructure, etc) are better included in building costs — that’s a reasonable argument; I’m not against such regulations, or we wouldn’t be living in San Francisco. But I think it’s worth being clear that more regulations (all other things equal) will increase the direct costs of housing.

I am not in the industry, but I have seen people in the industry use handlers who specialize in appeals to various regulatory agencies, just as they have lawyers on staff, which small homeowners don’t have.

The paper you quote, like several others, finds a correlation between regulation and price, which makes sense but does not prove that one causes the other. Rather, there are more restrictions on building in a crowded area, and crowded areas are more expensive. To explain by example, houses in the rural Central Valley are cheaper than in SF, and there are less regulations there. But the reason there are fewer regulations in the valley is because it’s not built up. You may be able to build a 10-story apartment building there, and not worry about traffic impacts, but no one would want to.

When I look at the data, it appears that the number of people in SF per housing unit has been fairly stable over the past several decades: 2.1-2.2 persons/housing-unit since 1970 as per census data. But I’m not sure that sheds much light on whether housing construction is matching demand or not. Economics would normally predict that the price will stabilize at a level where demand and supply are balanced. I think it’s reasonable to conclude that prices are so high because the demand for housing at half the current price would be much larger than the supply.

My response is to the implied selfish aspect; but more than that, I don’t think of growth as a zero-sum game.

Are you speaking from experience in that industry? Because that doesn’t match what I’ve read (though this isn’t my work). I think that political uncertainty is a larger issue than the specific example I brought up — but I also think that construction in San Francisco (and CA as a whole) is more expensive in part due to regulations (see e.g. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/usappblog/2016/07/07/why-california-is-so-expensive-its-not-just-the-weather-its-the-regulation/ …).

Only neoliberal purists celebrate unfettered economic growth that results in unprecedented and growing wealth inequality. You would’ve also objected to ending slavery because it would “stifle the economy”. All of your “scenarios” are unrealistic “just so” stories that have many unaccounted for externalities. When office space is created without a concurrent provision for the needs of the occupants, shortages and crises result. That’s the reality of what happens and has happened. Its not a zero sum game, new unsupported office space creates shortages that didn’t exist and wouldn’t have existed.

That is pretty much the entire point of his “Save Marinwood.”

NIMBY is always an inflamatory pejorative used to discredit people. Why not neighborhood leader?

Wow. That is not at all the key concept.

I guess not everyone is adept at reading science. Look at the question, look at the methods, look at the data the methods yield.

You cannot possibly answer a question about meeting demand for housing in a study that does not consider demand. It doesn’t even include a proxy variable for demand (e.g., pricing). Worse, the article presumes production is unfettered by regulations, which we know to be counterfactual.

This report is a living, breathing example of confirmation bias.

When there’s a shortage, population density goes up (as more people pack into a unit), and rental vacancy rate goes down. During the dot-com boom the rental vacancy rate went down to 1%, and even less in the Valley. During the previous decades, as the numbers I gave show, rental vacancy rates held steady at 4-5% or so.

(And if more units had been built then and occupied, how would they help us now?)

For a small homeowner, these regulations are a significant expense of time and money. For a large developer looking at hundreds of units, the cost is insignificant, and they have experienced staff dedicated to dealing with those regulations.

Having read through some analysis of SB827 and SB828 — I don’t think they are realistic (because they sound too drastic).

But if you did want to address the unaffordability of housing in CA — this is exactly the kind of legislation you’d want to support. I don’t really like the idea of taking away almost all local control, but — I can see the argument that if we want to get a different result, we’ll have to try something different, and this could work. I’ll have to think about that some more; I’m not sure if I support these bills as they are, but I think it makes sense to find some way to change the calculus that local agencies face.

I understand that NIMBY is usually a pejorative, and that may color my desire not to take that position; but I try to support building more housing, including where I live.

I grew up in the suburbs; I hated it. There are cities dense enough that I’d find them miserable, but San Francisco is far from that. I’d prefer more development than we have (both affordable and market rate, for all different market segments), especially if it’s in a location with appropriate infrastructure.

I don’t want to do away with all restrictions because the places I’ve seen which are closest to that wound up with sprawling metropolises that I find unappealing. I just think we can do a better job at this planning by biasing somewhat more towards approving development.

You’re legit weird.

This is such stupid analysis. As anyone in San Francisco can tell you housing costs/demand varies significantly across regions. Distribution is just as important as growth rates. The overwhelming majority of new home construction in California over the last half-century has been suburban while the most demand has accrued in urban areas. It doesn’t matter how many homes you build if none of them are desirable due to a lack of jobs and transit infrastructure.

The Bay Area is no exception, San Francisco has seen remarkably slow housing supply growth while places like Santa Rosa and various exurbs have seen spurts of rapid housing growth (almost exclusively single-family home green-fill development). It is doubtful that this sort of development could solve the housing shortage on its own partially because the potential supply is extremely limited by space and transportation infrastructure.

Tim doesn’t work a real job anymore so he can be forgiven for not understanding a) that tech is only a portion of SF’s work force and b) that trends driving urban job growth are national. San Francisco is the site of a particularly bad housing crisis because of our failure to adjust to national economic trends that incentivize both companies and job-seekers, in virtually every service industry (aka every growing industry in the US), to relocate to urban areas.

Plenty of other cities are encountering the same problems with housing shortages that San Francisco has. Virtually every growing industry (tech being one example) has shifted back towards large urban areas over the last two decades. The geography of the American economy has fundamentally changed. It has very little to do with the specific industry and everything to do with the changing landscape of work in the US.

Only Nimbys ask “how can we curb office space, stifle the economy and limit the demand for housing?”

I know of two engineering firms that occupy an unheated warehouse in an industrial area and another engineering firm plus two tech startups that rent space in an unheated former auto repair shop. When you limit the amount of office space, the tech companies will go and “gentrify” industrial space, houses, you name it. So yes, you can limit office space and constrain the economy, but most of that pain will be on the older, more traditional businesses that are less efficient at making money and can’t compete for commercial space. It’s a zero sum game.

Re: Vallco, the original number of housing units was 400, now it’s 2400, and the office space has declined 10%. So it’s a way better arrangement than before. They also have to approve it in 180 days, so we’ll know shortly whether it goes forward or not. Yes, it’s possible that the developer will sell the entitled land, but again, we will know very soon.

Yes.

Also I’m guessing you didn’t like my previous question since it’s no longer here.

Paris is smaller than SF but has 2.5 times the population, and yet it also manages to be one of the most splendid human environments on Earth. And that’s because its boulevards are lined with 4-6 story apartment buildings, not 1.5-story glorified shacks, as is the case in most of SF.

I couldn’t help noticing the glaring lack of data from SF (as opposed to the Bay Area) in that little “study.”

Thank you for your reply Ed. I can say however from experience that there was significantly less housing prior to the first tech boom. It seems as though when the wells dry up re: boom(s) so does the development. Maybe if everything wasn’t about materialism could we find an acceptable middle. I don’t mind growth but not at the expense of life –

We don’t have unbridled growth but that is the threat of SB827. Changes could drive down the demand for certain demographics. Eliminating single family zoning could attract younger single childless renters but deter families with school-age children; and others that prefer single family less dense living; which, according to surveys is 70% of us. Would it lower the desirability overall is a good question? Will over development kill the golden goose?

There was an article in the paper awhile back that the glut of new units on SOMA was preventing the rise in rents there and maybe lowering them a bit; But far from enough to make rents there affordable. I suppose in theory we could build enough to lower the price, but would you want to live in SF any longer.

The inclusionary housing program helps very few and harms the many.

I think your position is very close to most people that I know who are labeled NIMBYs. It is always a pejorative meant to divide people. But it seems there is alot of us who recognize the need for housing while at the same time there should be the ability of communities to shape growth.

This is an outright fabrication from someone who doesn’t know anything about money laundering or the Bay Area.

So, you’re only against developments you don’t like?

You are the problem.

Actually, we can see through this example of deplorable reporting.

Why do you think it’s called 48Shills?

Thanks Tim. I’ve been looking for material to teach a class about the perils of tautological assumptions in social science research.

Very clever to omit data on demand and pricing. By the “logic” in this article, the McDonalds claim to have served “billions and billions” would constitute empirical proof that there is no hunger in any part of the world sever by that restaurant. I’m guessing you’d go so far as to make a claim of causality: McDonalds solved hunger.

This article is what goes wrong when there is no relevant editorial skill or expertise. Congrats.

Yes I am.

Btw, how do your daughters feel about your anti-housing activities?

Yes, and they are busy writing legislation that would mandate housing the homeless before any more housing for wealthy investors is approved.

Maybe I’m a YIMBY. I vote for propositions which make aim to make development easier. We also purchased our place in 2008. (In the Fall — we closed the week Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy; we didn’t buy because we thought things were going up. Not all neighborhoods adjusted equally though — I was surprised that a few mostly didn’t go down. I can believe tech contributed to those few neighborhoods.)

I was well aware of both the the frenetic pace of the housing market ’98-’08, and the subsequent bust. It hasn’t changed my belief that restrictions on housing development (along with market-distorting rules like rent control) play a significant role in the current high housing costs.

Doing away with all restrictions and rent control would be equally bad. I’d just argue for moderation (make housing easier to build, and make rent control adjust faster than inflation rather than slower than inflation — even slightly above inflation would be better than 0.6 of inflation). I don’t think that’s a panacea, but I think the strategies we’ve used so far will produce more of the same, and it hurts to see friends (and our kids’ friends’ families) who are pushed out of the city.

You are comparing the economic behavior of the housing market to beating children?

Why not invoke hippie love children to accuse him of being a materialist and the opposite of all that is virtuous and you?

Let me sum up your little screed: basically, the other commenter is wrong because he’s not you. As you are a model of suburban virtue, you are entitled to call anyone who works and would like a plac to live “neoliberal capitalist whiners”, even as you defend indefensibly restrictive policies that have made SF th most expensive city in the country.

Exclusion is awesome since it means you super virtuous suburbanites don’t have to mix with people who work for a living. Also, you get to lecture them about why they’re bad and you’re good.

You’re misleading in writing the Cupertino project is creating housing. It’s recent and only been proposed. And that proposal includes 1.8M sq ft of office space which will bring more new people than 2402 units can house. The housing imbalance is even worse than it looks because the new office space won’t be occupied by workers qualified for “affordable housing”.

How hat NIMBYs don’t get is that SF is not and will never be the suburb they want it to be. SF is nowhere near “overpopulated”. You people have some weird suburban expectations about density and housing that you’re trying to graft onto cities.

SFs population could easily double and the city would be easier to navigate because transit would have to take precedence over private vehicles. You’ve clearly never been or lived in a dense city.

NIMBYs want their suburban single family homes, street parking for their SUVs and all white schools. Move to Atherton. We live in cities because we like cities. Go find a suburb that suits your preferred lifestyle.

Yes, it is California’s fault.

http://cdoovision.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/map-of-population-density-us-usa-population-density-per-square-mile.jpg

Is that supposed to be a critique? Perhaps you should criticize doctors without borders for not volunteering at the boys and girls club as (or maybe they do???)

I’m sure there are some people who volunteer at the soup kitchen then head to the planning meeting to fight affordable housing in their neighborhood.

“The question is, if we have unbridled growth will SF lose what attracted you to come in the first place.”

I don’t think we have unbridled growth — except in costs (because when supply is limited and demand is inelastic, prices increase). There are changes that could make me less happy living here — but they’d also make it generally less pleasant and could also drive down demand … so they might be self-limiting.

I like efforts to make the city affordable. I just don’t think that affordable housing projects will be able to come close to providing enough housing to drive down costs — though I’m happy to see us construct more affordable housing, it’s just not enough unless we also focus on making more housing for other segments as well.

Whether or not your statements is true, it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t change. If your parents beat you as a child it doesn’t mean you should continue that behavior with your own children.

My experience is going through and pricing out what it would cost to do work on our property — not large scale construction. Construction costs ($/sq ft) are easily available; I’ll agree that comparing regions is difficult, but I spent a fair bit just to establish that there was no particular historical value for a structure on our property; and zoning restrictions make additional construction difficult. Looking at other buildings nearby, it’s clear that this hasn’t always been the case.

Why do you go immediately to insults? Are you unsure of your own arguments?

I don’t think I claimed land value wasn’t a major component. But — through relatives, I’ve also seen the real estate market in Tokyo. The land there is expensive — but there is a lot more flexibility with how it’s used; lots are frequently subdivided to make more houses (and less yard space). The result isn’t cheap housing, but it’s much cheaper than San Francisco is now.

Obviously you might not want to live in a city that’s laid out as Tokyo is; this is a reasonable position. But claiming that expensive land makes (relatively) affordable housing impossible seems only true if you accept a number of additional constraints.

My response was to recent changes in the housing market. The article has some interesting information which does rebut part of Scott’s claims — pre-90s, this does suggest that housing was keeping up with demand. I’m asserting (and there are lots of other sources you can find for this assertion) that in the past two decades, part of why housing hasn’t kept up with demand is the cost of building it.

I went to UCB from ’93 to ’96; I started working in SF in ’96, and moved here in ’98 [mission, then sunset]. I lived in Mountain View from ’06-’09, before moving back to SF [noe valley]. I’m not sure if this makes me recent transplant or not (I moved to the Bay Area at age 18), but I’ve considered this home since I came. I was well aware of the anti-techie movement in the 90s as well; it leaves me with a lot less sympathy for the current wave.

It’s easy to demonize the other; I just don’t think it’s a very admirable impulse. (And — there are plenty of natives who also “worship the almighty dollar”.)

Regardless — it wasn’t my intent to whine — I was just pointing out that the results (expensive housing) are at least partially the consequences of policies the residents here have chosen. And continuing the current policies is likely to produce more of the same.

I’d rather a less expensive city, and do vote for propositions which I think will keep the city vibrant (not an enclave for the rich). I just find it occasionally frustrating that people’s choices often look (to me) like irrational responses which will only make things worse.

They also work in soup kitchens and help old ladies cross the street

Toxic dirt…ready for YIMBY housing now…got no problem with that

Nah, just confused. Production responds to trends in population, adjusted for income levels. So, for example, YIMBYs often assert (out of thin air) that a zoning change in Berkeley in 1973 crashed development there. What they aggressively ignore is that, at the same time, the biggest bulge of boomers was aging out the university. Wild inflation was helping to fuel displacement. The population of Berkeley was falling by something like 1% a year. Why should it be a surprised that new production cooled off during this period?

Region-wide, employment levels and tech growth are really hot at some period of time, but over the course of 20-30 years they are reliably extremely volatile. That is also the same timespan on which the value of new production is measured.

What’s perhaps interesting in the most recent years is that we appear to be settling in to a “new normal” of how large median housing costs are relative to median household incomes — and that’s not true only locally, there are signs of it around the world.

Simpleton transfers from the public to big $ developers are about the most naive, superstitious, least informed policy recommendations going (other then when, out of the mouths of some, such policy recommendations are simply greedy and cynical).

This is like comparing Amount of Food vs. Number of people who have eaten, during a famine and saying “Everythings okay”. Discounting everyone who wanted to eat but can’t.

How many people, in the middle class, would like to live in San Francisco but can’t? A number completely absent from this analysis.

That piece of data is misleading because it tells you much less.

-It doesn’t tell you whether housing production is low or population growth is high

-It doesn’t give give the existing population as context. When we added 322,000 houses in 1963 it meant more because the population was only 15M.

Feel free to make your own graph though.

No. That is false. There is always a lag between jobs/housing and this time it is more pronounced because of the Great Recession. It happens in every boom town, everywhere. We do not live in extraordinary times. Every since the Gold Rush days (and probably before) San Francisco has gone through these cycles. Only a prolonged recession or hit to the local economy makes prices decline. This has happened since Prop 13 passed. Its just like the drought. In the late 70s early 80s Mortgage rates were hovering around 18% and people were getting laid off. It was far worse than today. During World War II if you weren’t fighting the War, you were part of the War Effort and likely living in a rooming house because there wasn’t housing. Life is never easy.

Sure there’s a lag, but in the past we caught up. Now we’re not catching up, and the number of units of housing per person is declining.

Also note in the period of time since we stopped “catching up” we’ve also had rent control and prop 13, so we have removed the incentives that were there in the 50s, 60s, and 70s to to downsize and free up additional housing. That’s something this data does not show.

Yimbys show up so support ANY type of housing, including homeless shelters.

http://www.sfweekly.com/topstories/yimbys-and-nimbys-battle-over-new-navigation-center/

And remember SB35? That horrible Yimby law by that awful Wiener guy that was going to hand piles of money to developers without any local input and without providing adequate affordable housing?

So far it’s creating 260 units of housing in Berkeley, 50% affordable, 2402 units of housing in Cupertino, 50% affordable, and 130 units of housing in SF, 100% affordable. So before it was 143 units of affordable housing under local control, now it’s 1,318 units of affordable housing without local control.

It is far faster to open a company and install 100 cubicles than it is to build 100 apartments even with streamlined approvals. San Francisco has always had booms and busts. The lag between the job growth and apartment growth is the major culprit. Additionally the Housing bust meant fewer developers were will to risk building while real estate values declined. This will soon correct itself and we will see softening prices.

Great graph, what you need is a third line on a different scale showing the ratio of:

– added population

– new housing

This is alluded to at the end of your chart, but a dedicated line showing this ratio would help. Frankly Tim Redmond needs to get on top of this – because his data, specifically the 2016, is not substantiating his point.

The people YIMBYs represent are neither starving nor homeless. Lots of housing has been approved that is not being built — no one is stopping that. And in any case, the only thing being under-built is affordable housing and yet YIMBYs are all for taking up land for market rate housing instead. If you really cared about homelessness, you would fight giveaways to developers and lobby for only truly affordable housing.

Also, much of that pipeline is hunter’s point, which is not going to get built anytime soon

If you look at the data presented in the article, housing production lagged population growth from 1980-1990, 1990-2000, and 2010-2016. In the last 40 years the the 2000-2010 period was anomalous in terms of housing growth exceeding population growth. I put the data from this article into a graph to make the trend more clear:

https://i.imgsafe.org/e9/e96349e52e.png

If people were starving and they needed food would you mock them in the same way?

Housing is a necessity, not a frivolity.

Look at the data again, and tell me it supports the author’s claims:

https://i.imgsafe.org/e9/e96349e52e.png

If you actually looked at the numbers you might notice there has been a long decline in housing production, in both total number of units produced and percent growth. How can you blame the “pace of change” when it’s the slowest in living memory?

I put their data into a chart to make the trend more clear:

https://i.imgsafe.org/e9/e96349e52e.png

I put the growth rates for housing and population into a chart to make the trends more clear, you can see 2000-2010 is the exception in the last 4 decades, not 2010-2016. The population growth this decade is equal to or less than every other decade except 2000-2010. Note the each data point in their set covers growth for the prior decade, eg 1990 is 1980-1990.

https://i.imgsafe.org/e9/e96349e52e.png

Also note I corrected pop growth for 1990, it’s 1.7% not 1.5%.

I’m confused by Tim’s table – this shows new population arrivals and new housing have maintained fairly consistent ratios between 1 and 3, reinforcing his point. Then the last row, 2016, shows the ration jumping to over 5 – this seems inconsistent, suggesting new population far outstrips housing growth.

The author needs to address this issue.

Sure. Tell the seniors and homeless that would be moving into that building in Forest Hills not to worry, their living arrangements are in the pipeline!

And those that would move into the 500 or so units near CCSF that are deemed permanently affordable, also in the pipeline.

If you think the pipeline looks good you’d work to get it unclogged and plug all the leaks.

Not really, though. The numbers have no indication of demand. There’s an estimate that SF’s population would be twice as large if they built to keep up with demand. That buying pressure raises prices. If more had been built, the curve wouldn’t have been so dramatic, prices wouldn’t have rose so quickly, less people would have been displaced. The balance has been off for a long time.

Hence my comment about cherry picking.

What on God’s green earth are you talking about? You are being ridiculous. All of you. Spreading out the wealth is the only real solution I can see that will stop the destruction of the Bay Area.

What are you talking about? Most of us are not against all development but think it should be done to scale according to the neighborhood plan. We should respect property rights and local neighborhoods. The two are not mutually exclusive except in the minds of housing extremists pushing SB827 and SB828

I don’t think Redding and Modesto have the academic institutions churning out graduates that serve this field. Google “economic geography,” take a few minutes to browse whatever Wikipedia comes up with and get back to this thread.

But wait, aren’t your ilk the ones crying about artists and the elderly getting evicted? Yes, let’s not build and scale down existing projects so we can help these people out!

That all depends what your definition of “enough” is. The data shows that the number of people living here equals the number of homes x average number of people per home. If we build 0 homes next year or 10,000, population will change to match the number of homes because there is lots of excess demand. Is 0 enough? Is 10,000 enough? Over the last 20 years we built about 2,000 units per year. Tim thinks that’s too high. I think it’s too low.

Housing Supply equals population. I agree! The real issue is that supply will equal population at an equilibrium price. Currently that equilibrium price is ridiculously high. It’s great for existing owners like Tim and me. Not so great for everyone else.

Fresno?

It’s difficult to get Tim Redmond and Fernando Marti to understand something, when their dogma depends on their not understanding it.

Actually the chart you cite from Planning mirrors the data presented in this article.

You did see that he’s using Census data?

Thanks for pointing out what some of us have been thinking for a while. Too much too soon. The pace of change is to blame for the shortages. You can’t physically build any faster by passing laws. Building depends on labor and materials and financing.

If you can’t afford to live in SF there are many places to go. It is not suffering not to live in the City. Everyone I know came to SF voluntarily.

Even if what you say is true about the expense, it has NOTHING AT ALL to do with the data presented in this post. And if you can’t see that land value is a major component that drives housing costs, you shouldn’t be teaching.

Why is everyone attacking the author of this piece and not addressing his point that the causes are that residential building did not keep up with commercial building because the latter is more profitable, and more recently the tech boom brought in 10s of 1000s of people in a very short time. Why isn’t the tech industry promoted in other areas of the state and country as a partial solution? Why do we HAVE to have a tech boom here and only here?

This comment is written like someone didn’t read the article they are responding to.

Actually there’s tons of housing in the pipeline. But here we have the Amazon Prime generation. I want an Oompa Loompah and I want one NOWWWW!

YIMBY trolls as usual miss the point. You’ve been myth-busted. End of story. Contact your think tanks for new talking points.

The key concept is housing production lags demand accutely during economic booms. It has always been this way.

YIMBYs are mostly Millenniels who moved here within the last five years and never experienced the real estate bust in 2008-2014. Prices were dramaticly lower and people were losing their homes. No on was building. Suddenly we are in a tech fueled boom and there are few homes in the pipeline. Zoning had nothing to do with it.

The data doesn’t support Tim and Fernando’s claims. All it shows is both housing production and population growth have dramatically declined since 1950, with housing production declining at a faster rate. I put the data from this article into a graph to make the trend clear:

https://i.imgsafe.org/e9/e96349e52e.png

One thing is clear: housing production has declined dramatically over the last 70 years.

Regarding some specific claims:

1. “It’s a decade or two of extreme, unlimited growth in the tech industry

driving tens of thousands of workers, who moved here from somewhere else”

Population growth in the Bay Area was 0.8% from 2000 to 2016, which is much lower than the 1.9% average from 1950 to 2000. Hardly “extreme” or “unlimited,” and more like “below average.”

2. “Construction was booming 50 years ago, and 40 years ago, and 10 years ago”

The boom we had 10 years ago was much lower than past booms and roughly equal to average production from the 50s to the 80s. It also followed a relatively long period of low production:

http://www.mychf.org/uploads/5/1/5/0/51506457/chart-pic-2016_orig.png

it’s also worth noting the population was much lower during booms of the past, making them more meaningful. So lets adjust the above data per-capita:

https://i.imgsafe.org/ea/eab4556825.png

3. “It would have been almost impossible to build housing fast enough to keep up with that demand.”

In the 80s and 90s housing production in California trailed population growth by 40-50k units, and from 2010-2016 we had a deficit of 100k units. By most estimates we are currently 100k units behind annually.

Japan, which is slightly smaller than California and 73% mountainous/rugged/unbuildable, produces nearly 1M housing units annually(!) If they can do that it seems like we should be able to raise production from 100k units to 200k units. If we created as many units per capita as Japan, we’d be doing 300k units per year. We’re starting with a much lower population and more land, so it’s definitely not “impossible.”

4. “But the city didn’t “underbuild” because of Nimbys or CEQA or anything else.”

Many areas were being downzoned during this period, and the Bay Guardian (Tim’s former home) was making the claim that building apartments in aging neighborhoods “attracts low-income minority people to San Francisco,” bringing crime and quickly turning neighborhoods into slums (see “the ultimate highrise,” written by Bay Guardian staff). So yes, Nimbyism was alive and well even back then.

The American housing market is actually a preferred venue for money launderers all over the world. Rich Asians frequently buy American houses as a way to avoid taxes in their own countries. Mortgages can change hands so many times it can be very difficult to trace without a forensic analysis of a complicated paper trail. And yes, there is house and condo-flipping in many American cities although the real problem in the Bay is too many people want to live there and they aren’t making any more land.

Here are three articles that discuss historical trends in demand for housing in the SF Bay Area: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Francisco_housing_shortage

https://www.spur.org/publications/urbanist-article/2009-08-08/bay-area-housing-market

https://medium.com/@Scott_Wiener/yes-supply-demand-apply-to-housing-even-in-san-francisco-193c1b0c190f

Have you even read the article? It’s talking about historical supply and demand going back decades, not the current situation.

A lot of housing has been being built in recent years. Very little affordable housing has been built, and even that required an enormous push against developers.

Incidentally, Tim has been advocating the same positions when he was a renter: more affordable housing, and less office construction.

The article talks about historic supply and demand. Do you have numbers for 1960-2010?

Not quite. People can and do pack into smaller spaces when housing is scarce, and the vacancy rate decreases. That is not what the numbers show.

Here’s the photo of the groundwater supply pump homeboy — see the windmill? then if you know anything about SF you know the plastic tire turf field in feet away. Yum Cancer.

https://archives.sfexaminer.com/sanfrancisco/blending-contaminated-sf-groundwater-with-hetch-hetchy-supply-makes-it-safe-to-drink-experts-say/Content?oid=2779183

You must be one of those tools who would the prefer the soccer fields go unused and empty. Ground water collected under the turf????

Get a grip…and perhaps travel somewhere that is actually densely populated.

There’s data here, which shows that for most of the last half-century, SF has built enough.

If you mean, has SF approved every single project proposed, no it hasn’t, and the same is true for every other municipality in the world.

If you don’t think SF has historically prevented building through regulation, there is nothing left for us to discuss. You’re willfully ignorant.

We have so many people cramming in SF that we have to have plastic turf installed in our parks because of over use…and now 13% of SF drinking water is ground water from under plastic turf fields on GG Park’s west end…drinking water filtered thru crumbled automobile tire shreds. Over population = cancer. YIMBYs don’t get that. They want swell clubs to go to at night and avocado toast in the morning.

We are building more than 2,000 per year.

The actual “displacement” is not that high; depending on how you define and measure displacement. 60,000 leave the City every year. a small fraction of them were displaced.

“The real issue is displacement and rising prices” that’s a major issue issue, which Tim has discussed here before, but the issue of this particular blog spot is about the false claims, repeated forever, about SF historically preventing building, somehow.

It was over 5,000 units in 2016. There are 143,000 units in the pipeline. A 2017 report shows 5,875 units Under Construction; 30,000 Approved Units; 7,200 Proposed Applications Units; 16,450 Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs); 51,000 Soft Site Units, including Density Bonus Programs; and 15,575 proposed Rezoning Units.

It may be a chicken and egg question but your experience is more typical of the dynamics. People move to SF for the lifestyle and then find employment that will allow them to stay. For the most part employers with high skilled jobs came to SF because of the talented labor pool. Young educated people moving to SF caused the high paid jobs. The question is, if we have unbridled growth will SF lose what attracted you to come in the first place.

This is an A and B conversation C yourself out of it

Oh please, let me grab some tissue for you. I’m an SF native and can’t stand folks like yourself who live in this bubble. You do know that the Bay Area is very much the birthplace of modern computing, going back to the 70’s. I know you probably wish Silicon Valley was still orchards instead of the concrete/office park hellscape it is today, and I can see the nostalgia of that. But to throw out some revisionist history about SF as some beacon of dreams for newcomers and outsiders without mentioning its foundation as one of the West Coast’s epicenters of speculation is absurd.

I don’t work in tech but your fear of the boogeyman and using that as a point to argue that today’s housing issues are solely on them is ridiculous.

This article looks at housing production and population, but ignores the key statistic of demand. For example, in 2016, HUD studied demand in SF and the Bay Area, and found that there was demand for about 9200 houses and 19,000 apartments. This unmet need results in high housing prices. If the need had been met, prices would not be high and going up.

Tell this to people pushed out of their home with no where else to go because rents are so high and the affordable housing queue so long. Tell them that we built enough housing so their suffering isn’t real.

God you are so callous, just because you have a home doesn’t mean that others aren’t stuggling. If you are like other SF homeowners, you bought during the nationwide decline in city populations resulting in you becoming a multi millionare on the back of our nation’s systemic racism. Have a little empathy for those not quite as privileged.

We haven’t built enough housing until everyone has a home, and not a single person is displaced!

Correct. You state the obvious here.

Did you move to San Francisco December of 1999? What is your experience of the Bay Area outside of SF? It’s interesting you say you moved here long ago but yet don’t have a history that gives insight that this isn’t a long standing problem, its a problem that was created by the chic nature of SF as decided by Tech/piggy backers who don’t see that the Bay Area needs time to catch up with the demand of what they would desire to do which is turn this area into a tech hub. Then you have people like me who were born and raised in the Bay Area who do not worship the almighty dollar, and certainly not a industry which is actively trying to tear down the institutions of America and trivialize its values, who do not want to see the Bay Area as a Tech Hub. Mostly because I was raised with an ethic and foundation that is against materialism. Like many in the Bay were, from the immigrants, to former farm workers, to the hippies who just wanted to live in a peaceful world full of love. Now you neoliberal capitalist whiners of the me me me club want to come in and bitch and moan about what isn’t – sorry to go off there, but again, you moved here in the 90s? Please elaborate on the history you can offer as it relates to this area that isn’t based in wealth/starting a family and making the rest of the area responsible for your desire of those things.

The easiest way to assume away your problems is to ignore survivorship bias (as well as demographic trends such as the decreased household size since the 1950s). This crass analysis attempting to show that we have plenty of housing is disturbing coming from the head of a consortium of low-income housing nonprofits. I’m sure population is closely correlated to food production too even throughout a famine.

So how do you avoid survivorship bias? Use other measures such as comparative prices, migration, or construction rates. It would help if Tim were critiquing existing articles such as LAO’s California’s High Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences (2015) or Issi Romem’s California’s Housing Prices Need to Come Down.

If the main point is that population growth tracks housing production, then there is no point. Population = the number of people who have a house here, so yeah, if you have more houses, you have more population unless houses are empty (I guess all that worry about new condos bought by foreigners and staying empty is a lie too.) The real issue is displacement and rising prices. I’d argue we should build more than 2,000 units per year to reduce displacement and price growth. Tim wants to build less and has no real solution for displacement and price growth.

Much like that study that said that most homeless people on our streets are “formerly housed San Franciscans”, you can cherry pick any study you like, to get the results you want. Or in this case, you can simply commission your own and publish it as fact.

This article is written like someone who has never had to deal with the city agencies involved with regulating housing. It’s expensive — no question about that — but CA law and SF regulations make it all the more expensive.

Do you have experience in estimating and permitting housing? How much extra would you say CA and SF regulations add to the unit cost of an apartment building? Do you also include regulations for earthquake safety?

“bald faced lie”—dramatic, aren’t you? It looks like he was looking at data from a few years ago.

Anyway, the main point of blog post is the first part: “the rate of production generally tracked population growth [for the past 50 years]” That is the opposite of the claim Wiener et al. have been making (though Tim, politely, isn’t calling it “a bald face lie”.)

The table indeed shows that SF is building more than ever before. That’s with CEQA etc., and without SB827. So what’s your complaint?

And Twitter Tax Break And Free Tech Shuttles and Ed Lee Job Jobs Jobs and Cram More Sardines In

These are not facts.

“What the data shows is that, while the rate of production generally tracked population growth, often faster, it crashed in 2008, and even with the booming economy, it hasn’t come back.”

That’s a bald faced lie. Look at the real data on page 16 here:

http://default.sfplanning.org/publications_reports/2016_HousingInventory.pdf

Bottom line we produce about 2,000 new homes a year in SF. I wonder what that number would be if it wasn’t for things like CEQA, discretionary review, you, Calvin Welch, Aaron Peskin, etc.

I moved to San Francisco (in the 90s) after going to UCB; I grew up in Orange County. I do work in the tech industry, but I didn’t move here to work in it — I moved here because I wanted to live and raise my kids in San Francisco; and I work in the tech industry because it makes this possible. [I’m actually finishing an MA in teaching, and taught briefly, but am back in the tech industry.]

This article is written like someone who has never had to deal with the city agencies involved with regulating housing. It’s expensive — no question about that — but CA law and SF regulations make it all the more expensive. So saying that a lot is being spent isn’t the same as saying that we’re building housing as quickly as we can — especially when you have things like the 2014 Prop B.

The flip side is that I like living here — enough that we’re willing to pay for it. (We rented until late 2008, and we bought a flat then.) There are places with much less regulation over housing; housing there is cheaper but those aren’t places I want to live in. So I’m not exactly saying we should deregulate housing.

But I am saying that if you limit housing stock and make it more difficult to build — then prices will go up. And policies which make the city nicer to live in will also increase demand.

So this is probably pointless, but of course the population and the number of housing units track each other. There’s nowhere else for people to live!

Another way to look at it is the rental vacancy rate. For the 1970-1994 period, the numbers for the SF Metropolitan area are (US Census, Current Housing Reports):

1986 ····· 4.6

1987 ····· 4.9

1988 ····· 3.5

1989 ····· 2.8

1990 ····· 2.8

1991 ····· 4.2

1992 ····· 3.3

1993 ····· 4.1

1994 ····· 5.8

1995 ····· 5.9

1996 ····· 3.8

Population was growing, housing was built, and the bulk supply, as expressed by the vacancy rate, stayed the same, “NIMBYs” or not.

It wasn’t until 2,000[sic] that the city was back to its 1950-level population.

Well the population of SF is now estimated to be 870,887, and Bay Area housing construction has lagged population growth since 1980, so here we are.