Affordable housing and tenant groups that are opposed to the mayor’s plans to upzone much of the city to allow more residential development will be out in force Thursday/28 as the Planning Commission holds its first hearing on the program.

The Affordable Housing Density Bonus program could lead to massive displacement as developers evict tenants and tear down existing modest buildings to construct much bigger ones.

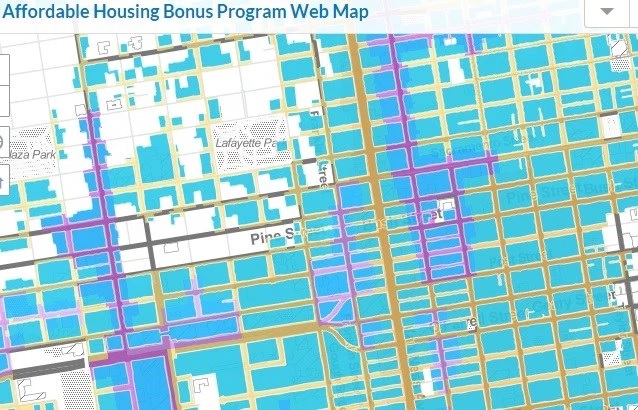

The idea, according to the Planning Department, is to allow more density than the current zoning permits on more than 30,000 lots all over town – in exchange for builders adding a few more units of “affordable” housing.

And I put the “affordable” in quotes because most of the new units will not be offered at rates that many San Franciscans can afford, and in some cases the law would allow developers to claim these density bonuses for apartments that aren’t significantly below – and sometimes may be above – market rates.

As we put it back in December,

It’s a gigantic change in planning policy, driven by the idea that the city of the future has to be built by destroying the city of the past. In essence, the proposal is aimed at making San Francisco a better, and possibly more affordable, city for people who are going to move here in the future, at the expense of existing residents.

Planning has made some changes from the original plan. Sup. London Breed has said she would introduce legislation to exempt rent-controlled units, but nobody has seen the bill yet.

And there are thousands of community-based business, corner stores, restaurants, etc. that could be displaced as property owners tear up buildings and replace them with higher-rent spaces.

But one of the most insidious things about this plan is that it gives developers the right to build higher, bigger buildings, with smaller back yards and less open space – and what the city gets in exchange is very little.

In fact, the current plan, based on an analysis by the new coalition San Franciscans for Community Planning, made up of tenants, affordable housers, neighborhood groups, and neighborhood merchants, would significantly reduce the city’s affordability goals.

Affordable housing in this city is linked to the average median household income in town, which is now around $75,000. Low-income housing is geared to people whose incomes are below 50 percent of AMI. Then there’s moderate-income housing, and people who qualify for that can earn as much as 120 percent of AMI.

Much of the housing in the AHDB program is aimed at people with incomes as high as 140 percent of AMI.

The difference is critical to developers. The standard for affordable housing is that nobody pays more than 30 percent of their income in rent. So if you build for a household at 50 percent of AMI – that’s about $38,000 a year – you can only charge about $1,000 a month rent.

Build for a household at 140 percent of AMI, and you can charge $2,850 a month. Big difference to your bottom line.

So of course, developers love the higher AMI levels – and for much of the AHDB program, 140 percent of AMI is just fine. In fact, under the program, only 12 percent of the housing would be restricted to households at 50 to 120 percent of AMI. Another 18 percent would be set aside for households from 121 to 140 percent. And 70 percent would go to people at or above 140 percent.

Oh and by the way: If you demolish a building with four affordable rent-controlled units and build a new one with 10 units, and simply replace some of the affordable units you destroyed, that counts toward the bonus.

Let’s look at that for a second and see how much of a burden this puts on developers, and what the city gets in exchange for very favorable, and profitable, zoning changes.

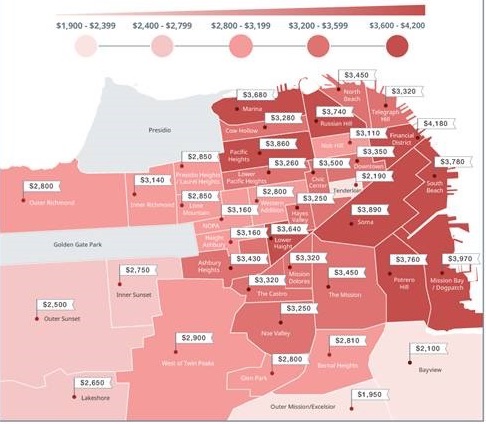

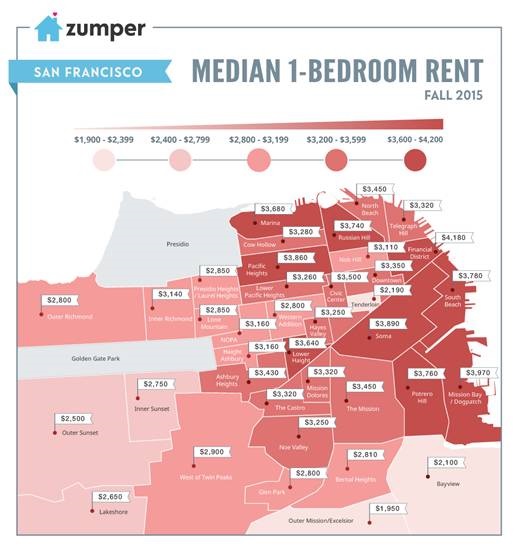

If you look at this map of median rents, there are at least 10 neighborhoods where the median rent for a one-bedroom is at or below 140 percent of AMI. That means if you build in those neighborhoods, charging 140 percent is the same as charging market rate. (Granted, the median rents include existing rent-controlled units, and the median rent for vacant apartments may be somewhat higher. But spend some time on Craigslist; in those neighborhoods, rent for a one-bedroom apartment is often below $2,850 a month.) So in many parts of town, the developer gets a bonus – the ability to construct more units in lower-density areas. And the city gets nothing, nothing at all.

Obviously, if you build in the Mission, or Noe Valley, or the Haight, or Potrero, renting a place for just (just?) $2,850 a month means you are losing potential income. But you are also getting obscene rents for the rest of the units.

But many of the most attractive sites for this upzoning might fall in the outer neighborhoods, where new buildings could tower over the existing ones – and the developers would pay nothing for that privilege.

The city’s housing element, the analysis shows, calls for 56.6 of all new affordable housing to be built at 50-120 percent of AMI. In the past seven years, the actual production has been close to 35 percent for the lower end of the income spectrum, so we’re falling behind.

The AHDB program goals: 12.5 percent of the housing is set for what we might actually call low- and moderate-income people.

So here’s what we are looking at: A plan that would allow massive demolition and displacement, drive a lot more expensive housing construction – and give the city only a relatively small amount of affordable housing in the deal.

How is this good for San Francisco?