The start of Black History Month may still be a couple weeks away, but needless to say there’s plenty of reason to get a little ahead of ourselves in that regard, as recent years have in many respects seen the clock turned back on US race relations half a century or more. The civil rights movement certainly did create sweeping changes in American society, but as with so many other social shifts that kicked into overdrive in the 1960s, it’s a mercy its proponents couldn’t foresee the degree of reactionary pushback the then-distant future would bring. Weren’t we supposed to be living in 2001: A Space Odyssey? Instead, post-millennium ‘Murrica keeps evolving towards something more like … The Purge? Network? Get Out? Idiocracy?

In any case, two new films releasing this Friday cast an instructive look back at major figures and events of the civil rights struggle that, needless to say, have as much relevance as ever these days.

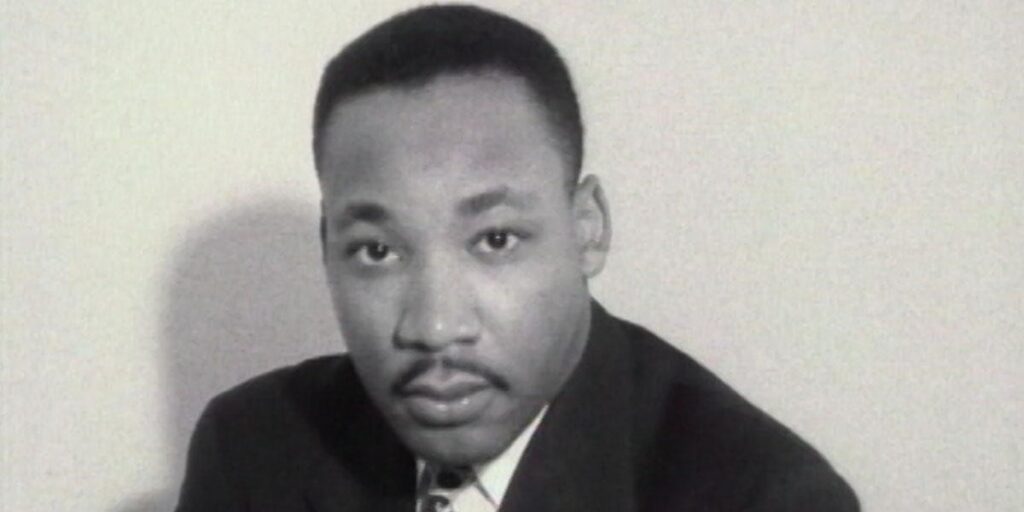

Actually arriving right on time (this being the long weekend of Martin Luther King Jr. Day) is MLK/FBI, which is available now On Demand. This fascinating documentary by Sam Pollard, whose Mr. Soul! was also recently covered in this column, delivers exactly what the title promises: A chronicle of how our government’s primary domestic law enforcement agency monitored the activities of the era’s most prominent racial justice activist for years before his 1968 assassination.

The extent to which Baptist minister King provided any “threat” to national security that would justify such close FBI scrutiny—eventually extending to outright harassment in various forms—is highly debatable, of course. But the film makes clear how the agency’s actions made internal sense within the general cultural context of the time, when (at least initially) far more Americans “trusted” J. Edgar Hoover than supposed rabble-rouser King. And above all, those actions were driven by the reactionary conservatism, egomania, and malice of Hoover himself, who was in complete charge of a vast, secretive intelligence organization for an unprecedented 48 years. That was long enough for our society to undergo enormous changes … nearly all of which the FBI chief resisted, utilizing every dirty trick in the book.

Entirely composed of archival visuals (there’s some latterday audio interviews and commentary), MLK/FBI uses recently declassified documents to reveal the extent of Hoover’s underhanded hostility towards “racial agitators” in general, and King in particular. The Fed honcho probably really did believe civil rights advocates wanted “civil war between races”—though one might argue the FBI’s skullduggery (here and later with the Black Panthers, et al.) only exacerbate tensions.

King had already been under “observation” by the agency for some time when the 1963 March on Washington and his “I Have a Dream” speech “turned a Southern movement into a national and international” cause celebre. An FBI memo promptly dubbed him “the most dangerous Negro in America.”

Hoover had long branded himself and his agency as crusaders against “crime and Communism;” now he used suspicions of the latter to taint MLK’s stature. King did have some key allies (notably progressive white lawyer Stanley Levison) with past ties to the Communist Party. But after being advised to do so (including from President Kennedy), he distanced himself from them. And as he’s duly seen asking a TV interviewer here, what could testify more to Black Americans’ patriotism than the “amazing” fact that so few of them had embraced Communism, despite their treatment by our democracy?

King is seen exhibiting the patience of Job over and over again, refusing to rise to the bait of loaded questions, his non-violent resistance even blamed for “inciting” white racist violence. His poise must have infuriated Hoover no end. Surely J. Edgar was apoplectic when this foe won the global approbation that came with his Nobel Peace Prize. Likewise when MLK came out against the Vietnam War—something Lyndon B. Johnson took as a personal betrayal, and which many in the Black community (who felt King should stick solely to civil rights issues) found problematic as well.

When the “commie” thing didn’t pan out, Hoover pushed agents to find dirt in King’s private life, bugging nearly every place he might go. That included hotel rooms where he purportedly cheated on wife Coretta. It is amusing to see Hoover lying on camera, claiming the FBI almost never used wiretapping, and only in cases of treason or espionage … just as he was frantically trying to catch MLK in the private act of infidelity in order to publicly assassinate his character.

The more literal kind of assassination on 4/4/68 curtailed that operation; a coda here notes that the voluminous tapes recorded won’t be declassified until 2027, at the earliest. Will they tarnish King’s legacy? Almost certainly not to the extent that his nemesis hoped—though even the whitewash of Clint Eastwood’s 2011 reclamation job J. Edgar couldn’t put the shine back on the FBI’s long-since-fallen fallen star, whose own peccadilloes are now painfully well-known.

Based on the book The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr.: From ‘Solo’ to Memphis by David J. Garrow, MLK/FBI illuminates depths of surveillance and intimidation normally unseen outside exactly the kind of Eastern Bloc totalitarian states Hoover thought he was protecting us from. (His agency even penned “anonymous” blackmailing letters in attempt to push King towards suicide.) Pollard manages the suspense of a spy thriller, using old movie/TV clips to place these events in the cultural framework of Federal agents’ romanticized popular images, as well as African Americans’ scurrilous ones. (It is not ignored here that Hoover’s plan to expose King as a philanderer would play on white society’s deep-rooted terror of “black sexuality.”) It’s a completely absorbing, stranger-than-fiction tale—though of course, our political realities have lately been occupying that zone 24/7.

Of considerably overlapping interest is One Night in Miami …, esteemed actor Regina King’s first directorial following several years’ behind-the-camera TV work. Based on the 2013 stage play by Kemp Powers (also co-director/writer on the current Pixar ‘toon Soul), it’s a fictive depiction of the 1964 evening in which Malcolm X, soul singer Sam Cooke, star NFL fullback Jim Brown, and the boxer then named Cassius Clay gathered in a hotel room to celebrate the latter’s win over heavyweight champ Sonny Liston.

That unexpected triumph puts the already-acquainted quartet in a party mood. But Malcolm (Kingsley Ben-Adir) is not about to condone the pursuit of alcohol or pussy—despite his already being somewhat at odds with Nation of Islam leadership. In fact, he’s called the others here for another reason he’s slow to spell out, one that asks them to use their leadership status for common good, rather than basking in the glow of individual achievements.

It’s a somewhat argumentative summit of titans, with X acting as an often humorless scold towards Cooke (Leslie Odom Jr.), Brown (Aldis Hodge), and even recent Muslim convert Clay (Eli Goree), who just days later would announce he’d rejected his “slave name” in favor of Muhammad Ali.

Snapping “You bourgeoise negroes are too happy with your scraps,” he berates them for insufficiently using their fame to lift up all African-Americans. This isn’t necessarily what three deservedly healthy egos want to hear, or even deserve to. They push back, ennumerating their good deeds and pointing out Malcolm’s own imperfections. Still, at this white-hot key moment in the civil rights struggle, each comes away with a renewed sense of socially-conscious purpose.

Released in inconveniently close proximity to another African American historical imagining derived from the stage, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, One Night can’t help looking less successful as an adaptation to film. The text is more didactic, the action (even) more theatrical. Though King manages to keep the protagonists out of that hotel room for half an hour, with some additional flashbacks and other digressions later on, we’re always aware this is a dialogue-driven piece that might’ve felt more at home in a proscenium.

Yet despite its somewhat slow, artificial, and monotonous progress, the construct still has electricity, and the performances are strong—even if the actors may not always feel like ringers for still very-well-remembered public figures. (Among which only Brown is still alive, at age 84.) One Night in Miami …, which is available as of today via Amazon Prime Video, has the inevitable effect of an alternative Mount Rushmore come to life, trying to sustain mile-high legends while simultaneously reducing them to everyday scale. A certain amount of disbelief must be suspended just to absorb the lessons they’re made to learn and teach in the narrow dramatic window provided. Nonetheless, King, Powers & co. do succeed in making history (or something at least close to it) feel more immediate for two hours, as their protagonists weigh how to best hasten political change with personal commitment.