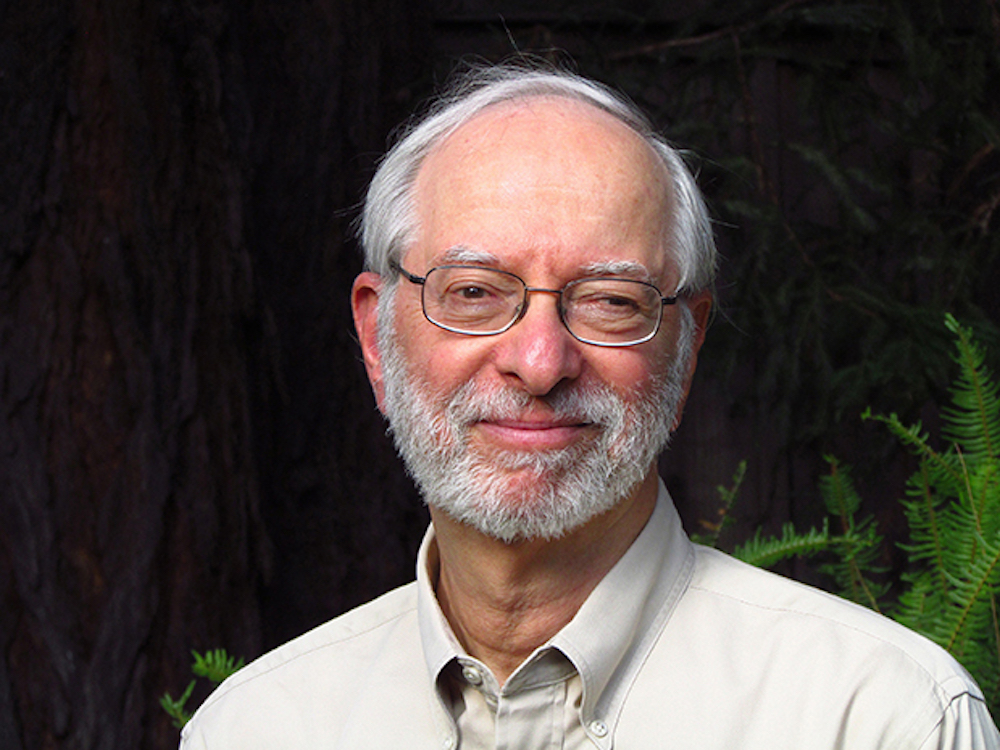

It could be said that writer Richard Kluger has been conducting research for his new book Hamlet’s Children (Scarlet Tanager, $21) for 89 years—ever since his birth in Paterson, New Jersey on September 18, 1934. Like Terry Sayre, the novel’s primary protagonist, the Berkeley-based Pulitzer Prize-winning author was once an American youth growing up in 20th century America. Kluger spent his early years on the Upper West Side of New York, living with his mother and older brother after his parents divorced. The childhood and teenage years of his book’s main character are cast against the same historic eras, but embellished and enriched with unusual trauma and far more drama.

Kluger’s novel introduces readers to its narrator Terry, an observant 13-year-old American boy living in Virginia with his mother and suffering the random and rare attentions of his biological father. His father’s family is wealthy, distant, troubled, and wants little to do with the unmarried couple and their child. His mother’s family is far away in Denmark, a place that seems entirely remote until a voyage overseas at age eight that has him meeting his relatives and learning their sometimes-sordid, sometimes-splendidly-colorful family stories. In the summer of 1939, his mother is taken ill, and Terry is offered asylum and care in his grandparents’ home located in a small coastal town, located at one hour’s drive from Copenhagen.

Soon after Terry’s arrival in Europe, the fire-breathing dragon of Nazi Germany rises to power. World War II begins, small countries like Poland and Denmark are crushed by the onslaught of Nazi military forces, and Third Reich troops invade and occupy the land and the people. The Danes must figure out how to survive in the face of constant life-threatening situations.

Notably, Terry possesses a unique “outlier” perspective on the war, and Kluger provides his narrator with an insatiable curiosity not unlike his own. This may explain why it seems that, during a phone interview with the author, he has been writing this book for decades. It’s clear Terry and Kluger share boundless energy; intellectual interests; survival instincts; efforts to comprehend issues related to masculinity, feminism, relationships, and power; and other features common to the adolescent boys who grew into manhood during the WWII era.

Kluger has written numerous books of fiction and social history, including the Pulitzer Prize-winning Ashes to Ashes: America’s Hundred-Year Cigarette War, the Public Health, and the Unabashed Triumph of Philip Morris, Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America’s Struggle for Equality, and others.

As a journalist, he wrote for the Wall Street Journal, the New York Post, the New York Herald Tribune, and Forbes. Later becoming executive editor at Simon and Schuster and editor in chief at Atheneum, he launched his imprint Chartreuse Books, before turning to writing books full-time. Hamlet’s Children was released in August in an original paperback edition by publisher Lucille Lang Day of Scarlet Tanager Books.

The book’s title is a mild riff taking advantage of the fictive man who is arguably the most famous Dane of all time. In a line from that Shakespearean play, Horatio says, “There’s something rotten in the state of Denmark.” The Danes in Hamlet’s Children (as theydid in actual history) choose “quiet resistance” to oppose the Nazis—the “something rotten” in the book is the anti-Semitism the Germans bring into Denmark’s egalitarian, peaceful society.

Kluger says his research for the book began decades ago. He was inspired by the story of how in 1943, after being warned the Nazis were about to mount a massive deportation of Danish Jews, just over 7,000 Danish Jews and roughly 700 non-Jewish family members were secretly led by ferry across the sea to safety in neutral Sweden.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

“Among all the other countries invaded, they were the only ones who saved their European Jews,” he says.

“I always wanted to write about the war: the most horrific military conflict in human history,” Kluger continues. “The question was how to do a narrative that looked at a long war in a compelling way. I think it was harder because I was dealing with a sensitive subject: How did the Danes save their souls without becoming compliant with the Nazis?”

Over the course of his career, Kluger has divided his prose between non-fiction and historical fiction.

“With historical fiction, my job is to create my own world that will cause the reader to suspend disbelief. That means I can play within the rules of known events. For example in this book, there’s a comedy act with Victor Borgen that actually happened. I use that scene thereafter by having the characters who attend his act refer to it, while making points that identify with themes I’m trying to develop throughout the book.”

Kluger does deep research, but does not map out an entire book before launching into the writing process. This means characters can “swim about and change,” and facts or characters can turn up midstream. The Danish physicist Neils Bohr, whose understanding of atomic structure made him valuable to the Nazis, was one such appearance.

“I found out he was a great theoretical physicist, and was allowed by the Nazis to stay alive even though his mother was Jewish,” says Kluger. “They wanted him to help them develop the nuclear bomb. I was able to use his laboratory as a way the characters conspire to fool the Nazis.”

The moral dilemma at the heart of the novel—Denmark’s “silent protest”—damaged many Danish people’s psyche. Some suffered profound shame for not having been outwardly aggressive to the Nazi regime.

“That is the main theme of the story and starts on page one of the book,” says Kluger. “The narrator in the first scene listens to a radio broadcast and his grandfather is greatly ashamed and wounded by his country looking spineless. Yet the book deals with what a person must do if facing a firing squad. I tried to spin the whole book around that. I didn’t want to be an apologist or an antagonist. They were in a very difficult spot and it’s a parable for any country conquered and ordered to do stuff for a hated captor.”

Relationships in Hamlet’s Children mirror the dynamics of contemporary power struggles and tensions, especially those touching on sexuality and sexual identity. Asked if this was a deliberate choice to amplify relevancy for today’s reader, or simply a factual situation drawn from history, Kluger says, “Sexual tension is part of human nature. I wasn’t trying to be timely; I was appealing to basic human nature that’s gone on forever.”

Writing Terry’s Aunt Rikki, whose relationship with a powerful Nazi officer is like a chess competition waged between masters of a game in which sex is the prize, required a deft touch.

“It’s written without showing a sex scene,” says Kluger. “Instead, I show how they act as patriots on opposing sides. How do they use one another without feeling like they are raging hypocrites? Rikki was more complicated because as a woman, she risked being seen as a seducer and collaborator without a justifiable reason.”

Delving into a time before the world wide web had Kluger reflecting on today’s information-sharing landscape.

“It’s been startling to have the internet, where everyone can go online and express their opinions,” he says. “It’s dominant and universal and local news has taken a major hit. In my story, the town newspaper allowed the family and owner of the paper to know about the community. I admit, what gets sent out now, in real life, sometimes has me yelling at the computer and TV screens. How does this news that’s not even real get on 24/7? Why are less people reading books and longform journalism? I know, books are hard to read and take time and concentration. People want easy and short, and these things are complex. It’s a difficult moment in the information age.”

But not so difficult that Kluger wasn’t able to complete his next novel on the very day of his interview. Titled The Swiss Account, it is the story of someone who inherits a titular holding and isn’t certain of how to proceed. With loads of research and writing completed, Kluger was left with only one task: finding it a publisher.

Purchase Hamlet’s Children here.