The Summer of Love and the Antiwar Movement in San Francisco gave birth to a lot of things, including The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, psychedelic rock, an enduring legacy of progressive activism in this city, some argue (for better or for worse) the digital revolution, and a whole lot more. (It was also an era of profound sexism, bad drugs, and a lot of other serious problems that get glossed over in the history.)

Among the things that era birthed, and was driven by: A radical radio station that started in 1967 on what was then a radical new approach to radio, the FM broadcast spectrum. KSAN, also known as Jive95, was a revolutionary as the music and politics it promoted, a free-form station where DJs played what they wanted, without a marketing department (or official censors) interfering, and where a group of young journalists developed a news department that was unlike anything anyone had ever heard on the air.

Dave McQueen, Scoop Nisker, Larry Bensky, Larry Lee, Paul Krassner, Bonnie Simmons, and so many others who became local and national legends got their broadcast start at KSAN. Nisker’s famous signoff—”If you don’t like the news, go make some of your own”—continued to live long after the station in effect shut down its left-wing rock ‘n’ roll framework in 1980.

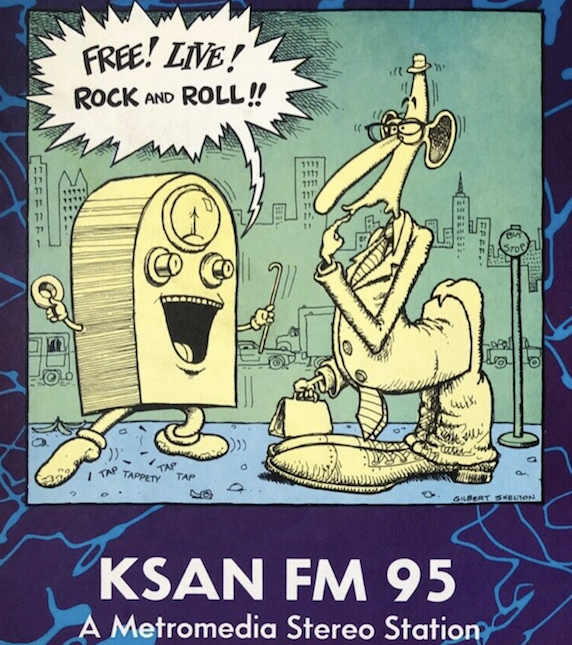

KSAN joyfully broke the rules, defying its corporate master, Metromedia, in New York, and sometimes the FCC (which didn’t react well to COYOTE founder and sex worker rights advocate Margo St. James giving Krassner a blowjob on the air—at least allegedly).

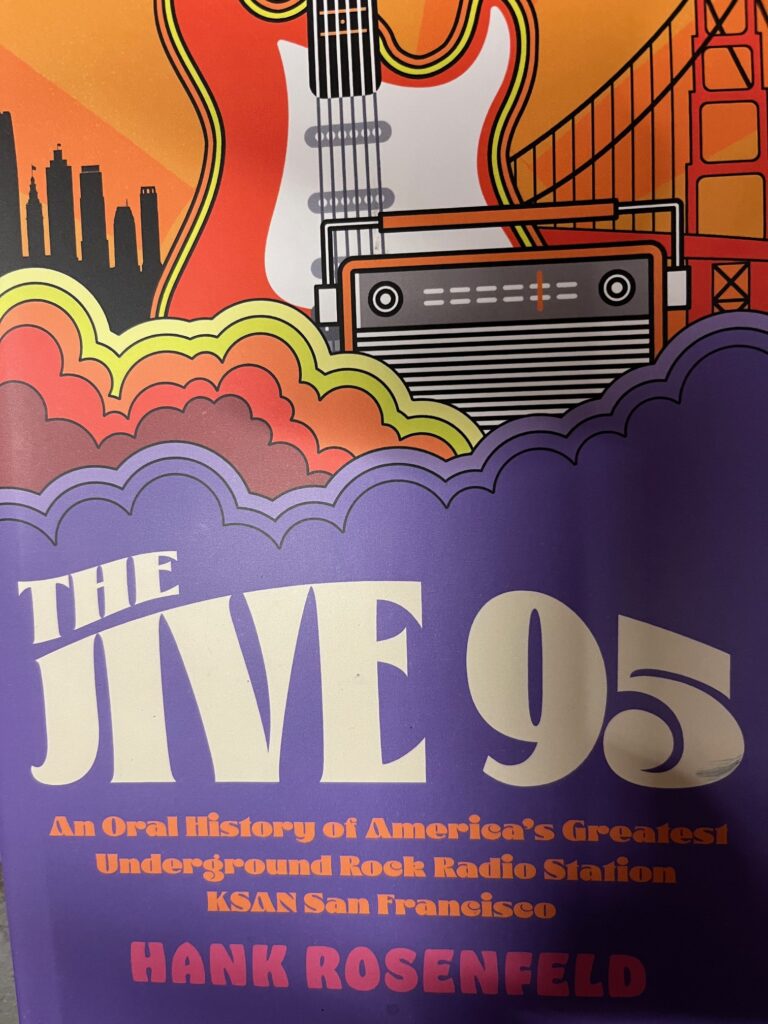

Hank Rosenfeld, who worked at the station in its final years, has put together a history called The Jive 95: An Oral History of America’s Greatest Underground Rock Radio Station, KSAN San Francisco that’s hard to describe—it’s basically conversations with a bunch of people who were there and are still around, talking about the madness and brilliance that changed radio, and journalism, at a moment when San Francisco was changing the world.

We caught up with Rosenfeld for an interview, and edited version of which follows.

48HILLS The book is essentially a print version of an oral history.

HANK ROSENFELD I hope it reads in different chapters like a conversation between folks about the adventures these characters went through. Bonnie Simmons and Terry McGovern called the station a Rashomon: you couldn’t get three Jivers to agree on a story.

48HILLS Talk about how you got the interviews with all these folks—and how hard it must have been to deal with the reality that some of the key figures (Larry Lee and Paul Krassner, and so many more), have died.

HANK ROSENFELD We lost so many Jivers in 2023. The phenomenal journalist, Scoop Nisker, my mentor in the “Gnus” Department, who had the memorable kicker to his daily show: “And if you don’t like the news, go out and make some of your own!” Talk about community activism. Jiver DJs Edward Bear and Dusty Street, producer Roland Jacopetti—all passed. These wild, creative freaks and heads from KSAN are elders and we communicated by phone and e-mail, and another great DJ, Norman Davis, said “please finish the damn thing while I’m alive.”

I’m saddest most that Scoop and Paul Krassner aren’t around to enjoy the book. Krassner was another mentor, and a great editor at The Realist, one of the country’s first countercultural magazines.

Yes, some of the creative kids are gone. I was very lucky that friends and families were generous with tales. I was also able to use interviews from Jesse Block, who produced the new KSAN documentary, “Something In The Air” with fellow Jivers Jim Draper, Eric Christensen, and Kenny Wardell. (There was one particular figure from the station who refused to share stories because she said she was saving them for her memoirs.)

48HILLS The book notes that KSAN emerged out of KMPX, which was a small radio station way at the end of the FM dial when FM was barely a thing. Tell us about how FM radio became the medium of the counterculture and how the veterans of KMPX started KSAN.

HANK ROSENFELD Right, KMPX was 106.9 and started up (a start-up!) just before the Summer of Love so everything was cooking in San Francisco at the same time. The station became the community hub for that young generation, living in urban communes and crash pads, pouring into the city from across the globe. KMPX was where they just came and hung out. It was the center of the world wide web of that time, attracting, as Dylan sang it, “every hung-up person in the whole wide universe.” The great “voice of god” newsman Dave McQueen said it was “broadcast by freaks for freaks.” A place for the kids seeking connection, believing the same things then, they were radicals against the war, fighting injustice, marching for peace and love. And always always, listening to the music that inspired their movement.

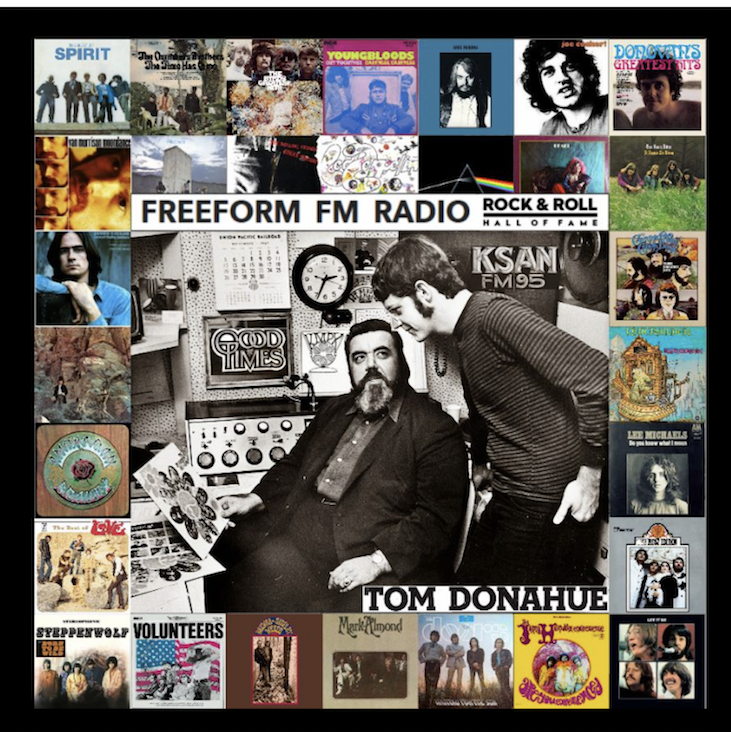

In 1968, the KMPX staff staged,”the first hippie strike in America.” They had their own union: the AAFIFMWW, which stood for the Amalgamated American Federation of International FM Workers of the World. Tom Donahue ended up taking everybody from Green Street down to Sutter where they started KSAN. KSAN was 94.9 on the FM dial (hence “the Jive 95”) and the workers had a wider broadcast signal, better equipment and wages. It was still the station everyone listened to. But you had the hippies versus the suits now—there were new owners.

48HILLS KSAN was owned by a big corporation, Metromedia, and yet they got away with so much anti-corporate, anti-capitalist, anti-war material. How did that happen and what were some of the conflicts your sources talked about?

HANK ROSENFELD Joel Selvin, the great music journalist from the Chronicle, said Metro had no corporate control on [Station Manager] Tom Donahue. None. As long as the station was making big dough, Donahue could tell them to go fuck themselves and they would say, “Thank you, Tom.” Selvin said Tom could do anything he wanted. Plus, they were on the other coast. Nobody’s signal reached that far back then! And today, there is no Metromedia. And Tom Donahue is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame forever.

But conflict was always there. Milan Melvin, one of the most amazing characters—hippie anarchist bolt of lightning (and at one point husband to Mimi Farina, Joan Baez’s sister)—Milan quit in 1968 because he said how could you use “underground” and “Metromedia Incorporated” in the same sentence? In fact, a professor named Susan Krieger wrote a book in 1979 about the station friction called, Hip Capitalism.

The corporate forces cracked down more and more: there were to be “no songs with drug lyrics!” etc. Metromedia had years of legal battles to keep their license after another outrageous incident led to a crisis: Dr. HipPocrates—Eugene Schoenfeld—who was popular for giving honest sexual advice to young listeners got an angry letter after one show that also went (as a “carbon copy” probably) to the FCC. Herb Caen detailed the escapades in his three-dot Chron column, writing how Eugene’s guest, Margo St. James (another fabulous infamous San Franciscan) had, “rising to a new low…out Lenny’ed the late Mr. Bruce,” on the air.

I always thought we fought back by keeping creative. Near the end in 1980, Steve Capen was calling himself KSAN’s “Morning Product” and we were calling the hated corporate empire, “Metromeaningless.”

48HILLS KSAN launched a lot of careers, both in music and media; I’m thinking of Dave McQueen, Larry Bensky, and Scoop Nisker (and somewhat, according to your book, Jimi Hendrix. It was also the voice of a generation in San Francisco. Talk about the legacy of KSAN and why it matters today.

HANK ROSENFELD It matters because the station is a hidden part of the history of countercultural revolution that took place in this country. It was like a musical vortex, with an enlightening vibe running back and forth between listener and broadcaster. That music goes on forever of course. At a reading at Copperfield’s bookstore in Petaluma, a woman in her seventies got up. She said she wanted her grandchildren to learn that Nana doesn’t just bake cookies for them and smell odd—patchouli still?—that she was part of an community of young Americans trying to change their worlds. That’s right kids, Grams was a hippie activist!

48HILLS Of course, like so much that happened in the 1960s and 1970s, it came to an end. Joel Selvin says it was just a matter of ratings, the KMEL (which later became one of the first stations to feature rap music) took over the top spot. Did the station change, or the audience change?

HANK ROSENFELD It had to do with the music industry.Some listeners didn’t like KSAN playing new wave and punk, pushing the musical envelope, being progressiveand breaking new artists like Elvis Costello. They’d had better ratings sticking with the Foreigners and Kansases, the industry pushed. Greil Marcus wrote at the time in a piece for New Westmagazine that while other corporate FM outlets were moving to the right, KSAN’s deejays were moving left. And that after Metromedia purged all the cool kids like Richard Gossett, Glenn Lambert and others, “the pods had seized control.” The new staff Metromeaningless brought up from Los Angeles played what the consultants told their bosses to tell them to play.

DJ Norm Winer, who came to San Francisco from WBCN Boston—one of the freeform FM stations that blew up across the land a year after Donahue’s experiment at KMPX—tells a heartbreaking story about watching, through the studio window, these goons putting a padlockon the door to the record library. He went on the air and said, “San Francisco, you deserve better.”

48HILLS Did Margo St. James really give Paul Krassner a blowjob on the air?

HANK ROSENFELD Paul’s friend Gordon Whiting says listeners had no way of knowing what was actually happening. Did they really? It was a ’70s zeitgeist-version, rule-breaking example of the “theater of the mind” radio tradition.

You can purchase The Jive 95 here.