Sheryl Oring listens attentively, there on a sidewalk amid Democratic National Convention week in the chronically political city of Chicago, waiting for me to dictate a letter to the future POTUS. I push down my feelings of annoyance over just having been forced to take a four-block detour to avoid a presidential motorcade (only during the DNC do you not know which past or present White House denizen held up your day.) Then, feeling a bit silly, I make her the medium for my communications with the next “leader of the free world,” or whatever, thanks to the performance artist‘s “I Wish to Say.”

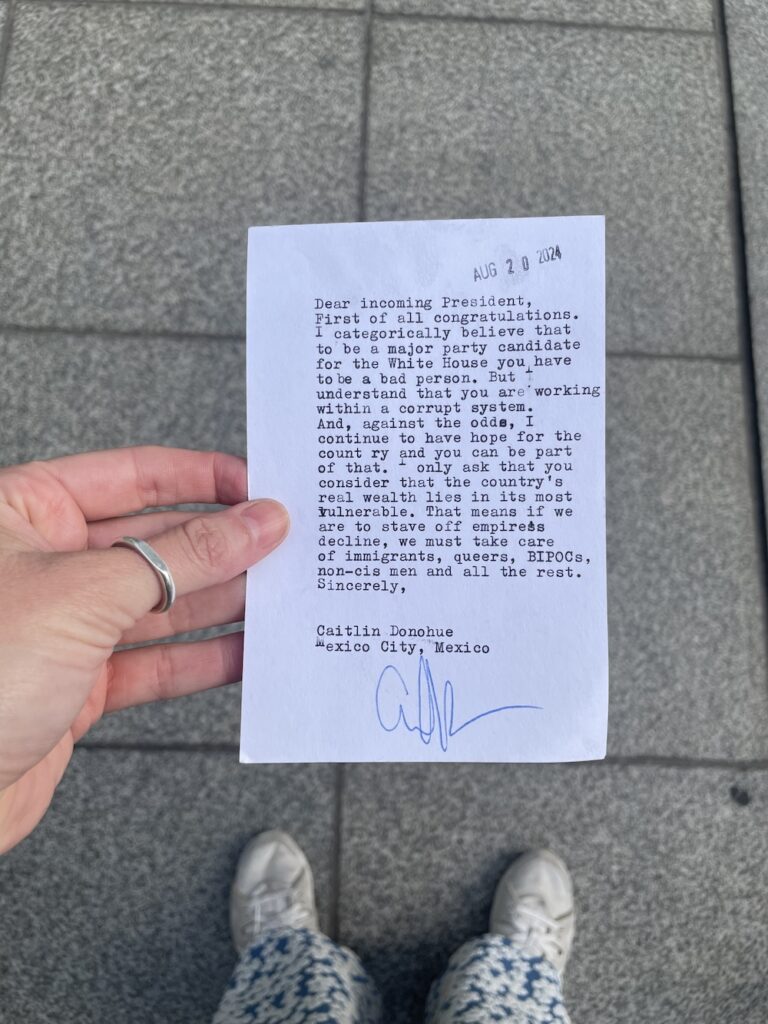

By the time her red-lacquered fingernails still on the keys of her retro typewriter, the letter we’d composed turns out far more eloquent—and a far cry more hopeful—than any of us should be allowed in the late summer of 2024. Perhaps the much-ballyhooed, brat-hued vibe shift has reached my grey matter, yikes.

Or maybe it’s proof of the power of Oring’s deceptively simple project. For 20 years, she has donned the attire of a 1960s secretary, a look inspired by her grandmother, who worked the desk at the University of Maryland’s political science department and Central Station, a 1998 Brazilian film following a woman who types up the letters of illiterate strangers in a train station. Thus armored in a pencil skirt, smart red lip, sleek beehive, and tasteful cleavage, she sets up an office on a card table and invites all comers to let her help them type up their letter to the president. She calls it “activating democracy.”

“I think of secretaries as being very powerful people, contrary to stereotypes,” Oring says. “They hold a lot of power, they hold secrets, they hold access.”

“I think that there’s something about the typewriter and my presence as a human being that gets people to be a little bit more thoughtful in how they speak,” she continues. “Even when people are angry, that anger is tempered in a way and it’s articulate and it’s real, it’s very human.”

I catch her in a state of emotional over-stimulation, at the tail end of a secretarial DNC week bender of three “I Wish to Say” sessions in two days. They have included one that morning at a truly fabulous radical event series called “F*** the Genocidal National Convention” and another that concludes with our interview, right out in front of the stately Museum of Contemporary Art in the businessman’s special of a neighborhood that is Chicago’s Streeterville.

Of course, such varied settings engender different kinds of letters.

“Earlier today, there was a lot of criticism from the left,” she says. “It’s absolutely not the case that the left is uniformly supporting Kamala Harris, especially when it comes to the war in Palestine and the climate, the economy, affordable housing, health care, those things.”

But perhaps it’s the intensity with which folks in Chicago are being forced to contemplate election season, what with this week’s wall-to-wall coverage of convention proceedings across local media (and on this very website!)—Oring has noted a certain fluidity in her dictators often lacking in our era of elected official fatigue.

And dare she say?

“There’s been a lot of—I want to say either hope or excitement,” she says of the past few days. “And I will say, even typing ‘Dear Madam President’—hypothetically, it feels amazing. I’m neutral when I type and that’s really important, but there is something, as a woman, in thinking that there could be a woman in the White House.”

She started the project back in 2004, in a different time. (The first performances were at San Francisco’s Canvas Gallery and Oakland’s Box Theater.) George H.W. Bush was elected that year and Oring had been feeling estranged from U.S. political realities, having moved to the Bay Area after many years of living in Berlin. She’d been creating sculptural art that had to do with censorship and thought up “I Wish to Say” as a way to reacquaint herself with her home country—and loose some tongues.

The grant money began to flow and soon, after debut performances in San Francisco and Oakland, she began to frugally travel the country, typing away. Two decades later, “I Wish to Say” has traversed the nation and most recently made many appearances in the swing states of Pennsylvania and North Carolina, Oring’s two home bases. There is a retrospective opening September 3 at New Jersey’s Monmouth University.

Her heart continues to be “touched,” she says, by her letter dictators. The day we speak alone, a DREAMer extolled the unmatched joy and resilience of those of uncertain immigration status and a chuffed young woman told her, “I don’t speak out a lot because I never feel like anyone’s listening to me.” That part—

“Listening is a really important part of this project,” Oring smiles. “I think that people respond to this personal, one-on-one exchange really well and they feel uplifted. That’s a nice thing to do. I feel good about it.”

Clutching my sweetly typed missive, after days and months of protest and polemic, I have to admit: for the moment, I do too.

For “I Wish to Say” upcoming national appearances and more on Sheryl Oring, go here.