“About 10 years ago while I was living in New York, I had a mystery illness that toyed with my brain and messed with my ability to move and speak. While stuck in the hospital, I had one of those ‘aha’ moments that made me rethink my life,” said Berkeley artist Mona Chiang in an interview with 48hills.

Though she acknowledges that it may sound like the plot of a saccharine TV movie, that strange and unexpected illness reunited Chiang with her love for visual storytelling. When she felt well enough to return to her job as a creator of toys and children’s books for a publishing giant, she found that all she really wanted to do was hide in a cave and create things for herself.

“I was perceiving things differently than before; words looked scrambled at times, while images became more vivid. Since I was unsure of my next steps, I decided to dedicate my free time to studying art—something I truly loved but had abandoned years before,” she said.

Chiang was born in Hong Kong, but spent her middle and high school years in Pennsylvania. College took her to Massachusetts, and her career, to New York City.

During her recovery period, Chiang struggled to figure it all out, juggling work, art school, and endless visits to the doctors. As if that wasn’t exhausting enough, she found out that her dog Yoda had also developed a brain disease.

“I was so confused and overwhelmed, I decided to quit work and uproot. Since my parents had long retired to the Bay Area, we made our way here,” she said.

These days, she calls the Gilman district of Berkeley home, initially drawn to the area because it reminded her of Brooklyn.

“It’s lively with people doing all sorts of interesting things. There are many art studios, wineries, and breweries. There are scientists, inventors, and restorers of rare cars. There’s a bagel factory and even a farm,” Chiang told 48hills.

It was a good move, the artist says. Yoda discovered the joys of wobbling around in off-leash parks and they shared a few happy months together in their new home. When he died, she felt a mixture of guilt and gratitude.

“I’m convinced that Yoda shouldered my giant list of garbage so that I could move on to better things, including making art. I suppose in the universe of bad TV, this would be when they’d cue the sappy music and throw in a sunset or something,” Chiang said.

But to be fair, Chiang says she always knew that her work would involve some form of creative storytelling—though it took a bit of meandering to reach her current art practice. She began studying art as soon as she could hold a pencil. At age three, she attended her first art school, though the era was short-lived.

“The lessons involved exercises in perfecting line weight and hand-eye coordination. I was more interested in smashing paint like Joan Mitchell. I was asked to leave after a few weeks,” Chiang said.

Her grandmother was unofficially her first dedicated teacher, but as much as she loved her, Chiang says she dreaded their drawing sessions. Her grandmother’s stringent approach came from her youth in Shanghai studying under the master Chinese painter Xu Beihong.

“He’s the guy most well-known for his galloping horses. Back then, I really hated his pictures, I thought his horses looked dead,” Chiang said.

Her grandmother was very exacting and made Chiang draw with her right hand, while she preferred using her left. Her fingers were often in pain from the death grip.

“Needless to say, neither of us were happy with my chicken scratch,” Chiang said.

Luckily, Chiang’s parents had the good sense to persist, again enrolling her in art classes in Hong Kong. She loved it but says the teachers were rather vocal about their preference for kids who were charming, obedient, and good at following directions.

“I, however, was the champion of spacing out. I was often made the example of what NOT to do. This led me to associate creating art with a sense of doubt and fear,” she said.

This sensitivity followed her into adulthood, when Chiang attended college at Mount Holyoke in Hadley, Massachusetts in the mid-1990s. Double majoring in Theater Arts and History/Asian Studies, Chiang took visual art classes on the side, purely out of curiosity.

“Since my old belief system had brainwashed me into believing that I’d never paint ‘correctly,’ I assumed there would be no future for me in art,” Chiang said.

After graduation, she made her way to New York City with the intention that she would continue studying playwriting or costume design. But quickly, Chiang got sucked into the demands of corporate life and art-making got shelved again. It took that unforeseen hospital stay to reconnect with her creativity, and soon she started spending weekends at the Woodstock School of Art. Since she couldn’t attend classes during the work week, one teacher provided homework and scheduled meetings for critiques to keep her engaged.

She says that because the people at the school were kind, she learned to tell the difference between constructive criticism and various forms of “critical babbling” which helped her gain the confidence needed to explore different ways of working. She knew there were things she wanted to say in her work but she didn’t know how to get there. Experimentation in abstraction—a genre she previously resisted—provided the breakthrough she was looking for.

“In my early years, I would study, sketch, and grid things out before I’d paint. It was what I was conditioned to do, and I didn’t feel safe deviating from the book. Over time, I found that that’s not the most effective way for me to tell my stories. It took a long time before I gave myself permission to experiment and to find my own language,” Chiang said.

The painting Perennial, from the 2018 series “Dictionary”—one of a group of works based on abstract interpretations of randomly chosen words using cold wax medium, oil paint, and wax pastel—is documentation of a shift in her approach. These paintings, along with more recent works, like Loud Mouths from 2021, illustrate Chiang’s breakthroughs in methods and materials, transporting her from one approach towards the next in a constant pursuit of new ways to express herself in alliance with personal change.

Lately she’s been excited to paint without brushes, using gloved hands, cotton swabs, or wiping cloths to play with shapes and texture. Sometimes in her work she intentionally makes things appear childlike to get her point across, calling it a device to jolt memories from adolescence. For the past two years, Chiang has been exploring the human experience through humor. She says she often views life as a giant trip to the amusement park.

“Sometimes you get on a thrilling ride. Other times, the ride could be vomit-inducingly bad, but you stay stuck to your seat. Or you might get totally freaked out in a fun house, despite knowing perfectly well that everything is fake. And the classic—and I’m very guilty of this—you keep crashing your bumper car into everyone you love,” she said.

Chiang says she contemplates all the weird rides we’ve all been on and tries to infuse that imagery with levity and hope. She wants to learn from each event, though she admits that is much easier said than done.

“Somewhere during the thought process, tangential ideas make their way into my compositions. I like watching people and eavesdropping. When I catch behaviors that make me laugh, scratch my head, or remind me of the plethora of dumb things I’ve said or done, my brain takes off on a very giddy adventure,” she said.

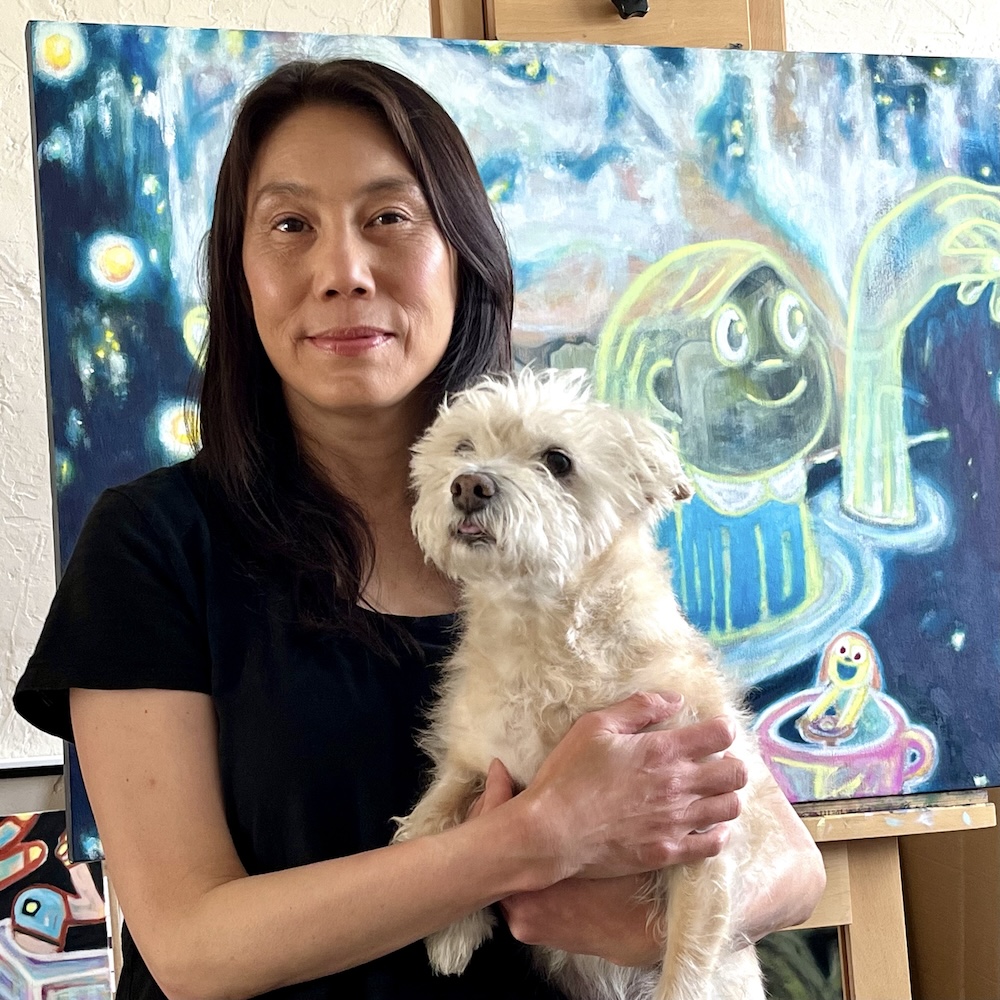

She also picks up on the behaviors of animals, especially dogs, saying they understand the flow of nature, live in the present, and are not burdened by giant egos. Another inspiration for Chiang is nature itself. Walking along the waterfront most evenings with her new dog, Rocket, they watch the sunset across the San Francisco Bay.

“Seeing nature at work never fails to remind me that we’re just specks in the universe. That’s one fast way to kick me off my high horse,” she said.

Speaking of her dog in an integral vernacular regarding her daily creative process, she says they usually spend the mornings getting their errands out of the way. Then the two of them become studio hermits after lunch.

“My favorite time to work is late at night when the world is quiet. But Rocket, my dog-boss-security guard, likes to keep a corporate schedule. So, we compromise. Aside from a dinner break and an evening hike, I work until around 10 or 11pm. That’s when Rocket starts grunting, telling me it’s quitting time,” she said.

In order to produce a whimsical vibe in her artwork, Chiang says the paint needs to conjure up a feeling of spontaneity or dance-like movements. And though humor is her end goal, she says she often processes through grumpiness, shame, and bafflement before she can reach it. Working on multiple paintings at once, Chiang says her studio looks like an easel forest. When she gets stuck on one painting, she hops over to another—literally, as she has a mini trampoline in her workspace.

“I bounce on it whenever I’m overthinking and spinning in circles. It’s amazing how jumping around can help clear my head. Painting is like solving a puzzle. There’s a lot of push and pull and moving things around. When things are going well, one might reach a magical zone of flow. This is not unique to me. Artists, musicians, writers, and many others often talk about this zone. There, you can’t tell if you’re doing the work or if the work or something greater is realizing itself. Nothing beats being in this zone,” Chiang said.

In such a practice, how does Chiang know when a painting is done? She describes that moment as a buzz-like feeling. She has been known to finish a piece in a few days, but most of her projects require weeks or months in a start-and-stop motion to complete.

“When I get the ‘stop buzzer,’ I need to trust it. If I don’t, I can overwork a piece and it will start to feel stiff or decorative. Then I have to play ‘kill your darlings’ to get the painting to feel fresh again,” she said.

Chiang is preparing for a solo show at SHOH Gallery in Berkeley that opens in October, titled The Human Circus, with parts of the exhibition to include interactive, audience participation.

“Together, we will explore the goofiness, the awkwardness, and the weird and absurd adventures of being human,” she said.

She says the gallery will be set up like a mini fun fair, with a mix of paintings and installations that represent carnival-like games for visitors to engage in. Chiang is eager to see how things will incubate to spread some positivity.

“The aim of each game is to have the audience use hands-on play to examine and poke fun at their everyday behaviors,” Chiang said.

Also planned are some free community events, with the intention that the unique dynamic of the show will encourage people to show up, connect, and recharge through humor, an avenue Chiang hopes will provide a welcome harbor in arduous times. One such event in the works is a doodling meet-up.

“There is a ton of research on the mental health benefits of doodling. Sure, one can doodle alone at home, but studies have found that happiness is contagious. So why laugh by yourself? Bring your pencils and coffee. No critique. No judgement. Just make art and laugh,” Chiang said.

Julie McCray, owner-curator of SHOH Gallery, says she was immediately drawn in when Chiang approached her with the concept for the upcoming exhibit.

“When first presented with Mona Chiang’s ideas for her new installation and exhibition, I was both intrigued and excited. With each hilariously brilliant description, my enthusiasm for this project grew exponentially,” McCray said. “Is Mona Chiang insane? Yes! In the best possible way!”

For Chiang herself, what’s exciting about her upcoming show is that she has no idea what to expect, as it’s a new way of presenting her work to the public and because it is partly a hands-on social experiment.

“It will be interesting to see how people will react to my paintings or engage with the carnival-like activities. Maybe they will laugh and carry that humor out the door. Or they might want to yell at me. Who knows!” she said.

Chiang welcomes playful interaction with viewers of her work in general. She doesn’t like to over-explain or impose a particular point of view on the audience. Providing some insightful clues through her titles, Chiang is more excited to invite us in through a more subtle doorway to wonder about what’s going on in her pieces and reach our own conclusions. She likes being a fly on the wall observing our reactions.

Using her own life experiences, both challenging and surprising, as a springboard for understanding what it is to be human in a demanding world, artist Mona Chiang is eager to share her stories with others. Going forward, she knows her work will endure multiple transformations based on wherever she is in her personal journey and how it prepares her for the next series of artworks. Thus far, she says she has learned not to take things, including herself, too seriously. She adds that maintaining a protective barrier on her time and space frees up a lot of room for creativity and growth.

“Who knows how I’ll be working in the future. Humans evolve. We learn new things. Maybe by next year I’ll be using chainsaws and popcorn machines!” she said.

For more information, visit Mona Chiang at monachiang.com and on Instagram. The Human Circus runs from October 4 to November 2 at SHOH Gallery, Berkeley.