The city’s new law mandating real disclosure for dark money in local elections is under attack – and the legal filing include some fascinating information.

Todd David, who runs the Housing Action Committee, a developer-funded group that advocates for more private-sector construction, has sued the city in federal court trying to overturn Prop. F, the Sunshine on Dark Money initiative that passed in November, 2019.

He argues that the rules are too burdensome, because they require campaigns to tell the truth about where their money is coming from.

Local political action committees have been using loopholes in local law for years to keep secret (until it’s too late) the actual source of funding for ads promoting candidates and ballot positions.

Here’s how it worked in the mayor’s race:

A state PAC called Progress San Francisco has put more than $200,000 into a superPAC that is called “San Francisco for London Breed, 2018, Sponsored by San Francisco Firefighters Local 798.”

Most of the money in that committee did not come from the firefighters union. Evan Williams, the founder of Medium, put up $50,0000. Chris Cox, a senior exec at Facebook, put up $9,000.

But the biggest money is from Progress San Francisco, which is also a state PAC that won’t have to disclose its donors until late May.

But in past elections, that group has been funded almost entirely by Conway, other Big Tech companies, and real estate interests.

Voters didn’t know when they saw campaign ads promoting Breed and attacking her opponents that they were funded not by the firefighters but by Big Tech.

Does that matter? Clearly, it does.

In fact, one of the most stunning elements of the lawsuit, which has received little press attention, is the declaration that David made under oath as part of his complaint.

In essence, he said that he can’t run effective campaigns if the voters who get his messages know that his efforts are paid for by, for example, the real-estate industry:

I have decided not to solicit contributions from the Realtors Association because of Proposition F’s on-message disclaimer requirement. Based on my experience in San Francisco politics, I do not wish to associate the Realtors Association with the Committee’s messaging because I wish to appeal to a wide range of voters citywide and I believe that including the name of the Realtors Association in our ads may risk alienating those “progressive” Democrats who tend to take a more antagonistic position towards business and industry. In my experience, Progressives tend to blame those in the for-profit housing industry, including realtors, for San Francisco’s acute and politically charged housing crisis. Progressives are a powerful voting bloc, having recently had a string of electoral successes in San Francisco (which is already a Democratic town) and I do not want them to be prejudiced against Proposition B by virtue of the fact that the Realtors Association would be identified on the Committee’s advertisements.

More: He wants to get money from wealthy interests, but those interests won’t give if they are going to be publicly identified:

I have solicited contributions from other committees that have previously supported my campaign activities and who I consider to be natural political allies but these committees have declined to contribute the requested amounts and to associate with our campaign. Representatives of these committees have stated that they are concerned by the fact their own contributors could be disclosed on communications by the Committee and other campaign committee recipients of their contributions.

In particular, these representatives are concerned that their committees’ own contributors may not wish to have their names and contribution amounts appear on campaign advertisements.

Jon Golinger, who helped write Prop. F, noted that “wanting to hide unpopular donors is not a valid reason to deprive voters of vital information.”

David argues that presenting all the data about the funders of a ballot measure could take up so much time that it would make digital video ads useless. He is supported by political consultants Nichole Derse and Maggie Muir, who also put declarations before the court.

Muir argues that “the disclosures will overwhelm and dominate communication by a ballot measure campaign or an independent-expenditure campaign because the focus will be on providing the funding sources of the message and not the actual content.”

Translation: If we have to tell you who is really paying for the ads you are about to hear or see, we can’t spin our message properly.

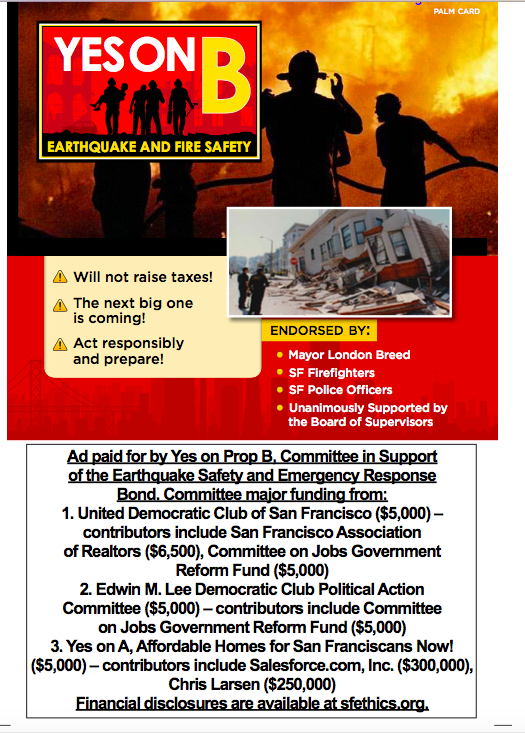

Muir made some mock-ups of how a mailer would look with a full disclosure for Prop. B, the earthquake safety bond that has little opposition (but that David has decided to do a special campaign committee for anyway).

Here’s what one of the ads might look like:

Yes: the disclosures take up a big part of the ad.

But if the consultants don’t like that, there’s an easy solution: Don’t funnel money through four or five different PACs set up to hide where campaign money comes from. Raise funds directly for the campaign, and tell everyone who is paying. Then the disclosures will be a lot smaller.

The reason this measure passed with 77 percent of the vote is that people are sick of dark money and big-donor Whack-a-Mole, where money pops up in secret places and it’s impossible to tell who is really behind a candidate or ballot measure.

It’s simple, Todd David (and Nichole Derse and Maggie Muir): tell us where the money is really coming from. Prop. F went on the ballot because a lot of political consultants and big donors (some of whom are now complaining about it) abused the existing loopholes to hide the money.

I emailed David to ask him about this; he told me he had no comment beyond the lawsuit and his declaration.

The case will be heard in federal court Feb. 14 at 10 am.