MEXICO CITY — Mexico is arguably the foreign country that has suffered the most from Trump’s callous racism throughout his campaign.

In the wake of his election, Mexicans have been left in limbo, forced to wonder about the president elect’s announced plan for his first 100 days in office in which Trump forecasts “the construction of a wall on our southern border with the full understanding that the country Mexico will be reimbursing the United States for the full cost” — not to mention the deportation and cancelation of the visas of “2 million criminal illegal immigrants.”

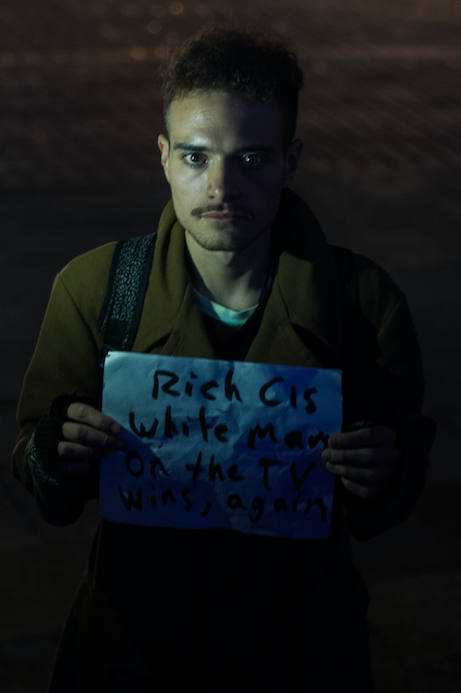

The hurt was on evidence among the small group that gathered at one of Mexico City’s best known landmarks for social protest, the Angel de Independencía, on Wednesday night to protest the Trump election.

While thousands marched in New York, Oakland, San Francisco, and other cities around the world, they formed a circle to introduce themselves and say why they came. A light drizzle built in intensity to a downpour.

Few left. The introductions grew to choked admissions of grief, confusion, hope. The group moved under the awning of a nearby hotel and continued to talk. They expressed fear over signs of racial animosity that have manifested in the US over the last 24 hours, including the (ironically, inappropriately placed) Nazi flag that briefly flew over a Dolores Heights home on Wednesday whose image was widely disseminated.

Elsewhere, Mexicans called the election a sign to shake off the neo-colonial oppressor.

“The future is Latino, brothers and sisters,” event producer Lucia Anaya, a.k.a. Derré Tida posted on Facebook. “Let’s stop gazing above and start building here below.”

But at the protest, grief needed first to be processed. Mexican citizen Atenea Rosado needed a moment before she could speak to reporters. “First, can we hug?” she said tearfully, pulling in friends for a series of embraces.

When she was ready, she told about her time in New York getting her master’s degree in international education from Columbia University. “I thought that a lot of Americans liked me,” she said. “And I know it is true, but I … somehow I feel they’ve let me down in a very weird way.”

Rosado is deeply concerned for the safety of Latinos in the United States. “I used to teach in Central Harlem so I’m afraid for the kids that don’t speak any English,” she said.

She had planned to return to the States to get her PhD in human rights education, but now she’s not sure that she’ll be welcome. Or if she wants to be.

“This is just far beyond any limit I thought it would reach,” she said. “This is … he’s a racist, he’s a xenophobe, he’s an anti-Semite, he is everything. And I don’t know how to understand it. And I want to understand it. I don’t want to blame the people who voted for him. I think fear passes from one to another as … I don’t know, as an epidemic. And I want to believe that’s it’s because [Trump voters] don’t know different people and that’s why they are afraid of us. But it’s still hard.”

How is Mexico to react to US’ election of a man who wants to literally wall it off? Because despite Trump’s histrionics, after centuries of US interventionism and disastrous trade deals, Mexico is inextricably linked to its neighbor to the north. Last year $24.8 billion in remittances from family members living abroad, nearly all of them in the States, exceeded the country’s total earnings from its petroleum industry.

“I feel it is just very close,” says Rosado. “Not because I lived there, but because I was raised in a place, in Mexico, that looks up to the US and that country seems to not exist. I really never had the American dream. I was very critical of the US and I’m still very critical of the US, but this is unbelievable. This is just far beyond any limit I thought it would reach.”

For US citizens living in Mexico, the election brought up deeply conflicted emotions. Some of Wednesday night’s protestors were the children of Mexican parents who had moved to the US for a better life who have returned to their family’s homeland. Many were stunned at the United States’ acceptance of bigotry. They were at a loss about what this could mean for them and their countries.

Melina (no last name given) was one of a group of Mexican and US citizen friends who organized the event. Melina is a Florida-born musician who has lived in Mexico City for the last year.

“I woke up in horror and disbelief,” she said. “I thought the best thing to do would be to be among other people who were maybe feeling similar things, try to find some sort of solace in other people.”

“I was following the election very closely and was horrified throughout and very upset,” she continued. “Maybe I felt even more impotent because I couldn’t be home, canvasing and phone banking like I would in another election.”

In contrast to many US residents who in the wake of the election results, posted about plans to move out of the country, Melina considers Trump’s election the dawn of a new era of social protest, one during which her birth country might need her.

“Honestly, right now it makes me feel like I have to return to the US and live there,” she said. “We need people on the ground fighting for our causes, fighting for women’s rights, fighting for Black Lives Matter, fighting to stop climate change.”

“We need passionate people there and — I don’t know if I feel guilty not having been there. But it does make me want to get more involved.”