The supes decided today to once again delay a decision on the 117-unit luxury condo project at 2675 Folsom, as the developer and community leaders continued to meet to see if there could be some kind of a deal.

At the same time, a new study by researchers at the University of California takes a hard look at the role so-called “transit-oriented development” plays in displacement, particularly in places like the Mission.

The study doesn’t make dense new market-rate housing in the neighborhood look like such a good idea.

The March 24 study, led by Karen Chapple, a professor of City and Regional Planning at UC Berkeley, runs about 400 pages and is packed with complex economic data. It takes a long time to read, and like many academic reports, is cautious about its conclusions.

But it makes a few remarkable statements that are not generally part of the San Francisco City Planning Department’s analysis of housing development.

“This study,” Chapple writes, “produces the strongest evidence to date of the relationship between transit-oriented development and displacement.”

Chapple is not a radical anti-development type. The report is nuanced, and carefully stops short of opposing market-rate housing in transit corridors. It’s full of the sort of language these papers often have — the data is not always conclusive, more work needs to be done, some regions are different than others. Yep. This is complicated.

But there are some facts on the ground that we need to discuss.

The study was funded by the California Air Resources Board as part of the state’s effort to figure out how to cut greenhouse gases – in part by cramming a lot more dense housing into urban areas with good transit access.

The problem, of course, is that a lot of that development will go into areas that have existing vulnerable populations – and if it’s done wrong, which it often is, the study notes that those populations will be forced out:

Overall, we find that TOD has a significant impact on the stability of the surrounding neighborhood, leading to increases in housing costs that change the composition of the area, including the loss of low-income households.

The study doesn’t say that transit-oriented development always displaces people; in detailed studies of Los Angeles and the Bay Area, it concludes that sometimes gentrification is caused by other factors, and development isn’t the only reason for it.

But it notes that:

TOD tracts in the Bay Area are changing more in the direction of gentrification than non-TOD tracts.

There’s a good reason for that:

The reduction in transit costs is also thought to increase land values.

That discussion was entirely missing from the debate around the Google buses. Sure, the buses get cars off the road, which is good. But they also make housing along the routes that they serve much more desirable to people who work in tech companies on the Peninsula, and many of those workers can pay more rent than the existing residents of the Mission. Thus: Evictions and displacement along the Google bus routes.

Then you get the interesting question of whether market-rate development near transit actually makes the greenhouse gas problem worse. The study looks at Vehicle Miles Traveled, which means how much people drive, and lover VMT are good.

If a lot of development takes place near rail lines (like BART), the residents are less likely to drive. But if, in the process, the development forces existing lower-income residents to move further away for affordable housing, and they have to drive to work, you actually see more VMT, undermining the whole idea of transit-oriented development:

Regional Vehicle Miles Traveled are likely to increase “if gentrification results in a reduction in the population living near rail.”

That is: Richer, smaller households move in. Poorer, larger households move out.

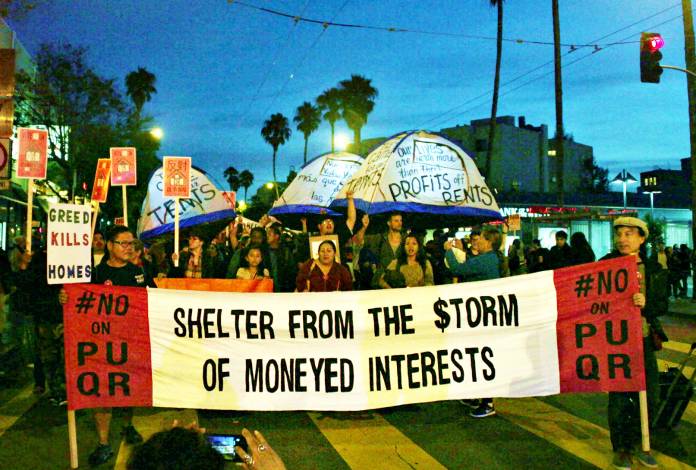

A statement from the Mission Economic Development Agency, Calle 24, and five other community-based organization notes that the Mission fits perfectly into that definition:

Between 2000 and 2012, while the rest of the city population rose, the Mission lost 4.8 percent of its population, median income increased by 48 percent (gentrification), and households with cars rose from 37 to 64 percent.

The other critical conclusion of the study – which seems to be obvious to everyone except city planners and supporters of more market-rate housing – is that “upzoning” – that is, increased density in specific areas, like the Divisadero St. corridor – is not necessarily a good way to bring down housing prices.

When the city upzones parcels, the study notes, property owners get a windfall – and are likely to charge more for the land that can be developed into housing. Simply put, upzoning drives up land values – and since the cost of land is one of the defining reasons that new housing is so expensive, maybe making land more expensive isn’t such a grand idea.

The community groups note that “this new displacement research is unfortunately absent from the City’s socioeconomic report on 2675 Folsom St.”

Whatever the deal on this one project, this is the kind of discussion we need to have. In some parts of town, like 23rd and Folsom (and 16th and Mission) new market-rate housing and the upzoning to make dense projects happen will absolutely drive up land values nearby. That will absolutely lead to evictions, rent hikes, and displacement of existing residents.

Is there a way to build housing in transit corridors, to keep people out of their cars, without forcing existing residents to move further away and drive their cars much more? Maybe – but San Francisco, where private developers set the agenda, hasn’t managed to find it.

For the half that stay – yeah. For the half that leave, probably not.

For the displaced, its most likely moving to a place with more crime, more litter (well, you can’t have more litter than SF, but …), lousy infrastructure (well, you can’t have lousier infrastructure than CA, but …) and poorer schools. For those who stay, the riff-raff have been removed or removed themselves; that is often considered an improvement in itself.

First the Gentry left the land; then they left the city; then they left the suburbs; and they’ll probably be leaving for high ground soon.

You want people to take public transit? Why not show some respect to the riders? Take the transit system out of the SFMTA enterprise network. Muni needs to serve the riders not dictate to them. Muni’s only priority should be getting people where they need to go. Muni should not be involved in developing neighborhoods or forcing people to do anything.

Is that a sincere question, Pope?

“The reduction in transit costs is also thought to increase land values.”

I don’t recall there being any reduction in transit costs lately, but, I think one can argue that proximity to “public transit” or a tech shuttle stop increases rents. Nearby properties are being priced according to proximity. It may not last long, but, that is the way it is now.

What’s wrong with gentrification? Is it a sin to live in a cleaner and better maintained neighborhood? Who invited the Commune to this discussion?

And, given 48hills’s mischaracterization of the study, the criteria for the Bay Area are hysterical.

One of the criteria required for a tract to be considered “gentrified” is that the percent of new market-rate housing in the tract is greater than the regional median. So new market rate housing near transit (what we would normally call “transit-oriented development”) is taken as **evidence** of gentrification, not an effect. This study is arguing that transit might cause market-rate housing, not that market-rate housing near transit causes gentrification.

Well that’s his job, isn’t it?

You could tell from the sub head of this article — “scholars” saying that building market rate housing is a bad thing. If they had clearly come out in favor of building housing they wouldn’t be “scholars”; they would be “paid college researchers”. You knew right away that this was going to be a whopper.

It’s more than just Tim being “on weak ground”; his write-up totally misconstrues the nature of the study. He’s either purposefully misleading people about what the report said, or lying about having read it all.

One clear sign Tim is on weak ground: Even the author of the study he’s misrepresenting says Tim’s anti-housing allies in the Mission are using the TOD study inappropriately.

From CurbedSF:

“Karen Chapple, professor of city and regional planning at Berkeley, writes in the abstract of the cited study that “[Transit Oriented Development] has a significant impact on the stability of the surrounding neighborhood, leading to increases in housing costs that change the composition of the area, including the loss of low-income households.”

“[Update: Chapple tells Curbed SF that although the Folsom project fits the definition of TOD as used in her study, leveling her findings against a single building isn’t really appropriate. “It’s apples and oranges,” Chapple says. “We did a study about neighborhoods, not buildings.

““It’s our fault,” she adds, saying that she plans to update the study with a caution against applying it to anecdotal examples, but emphasizes “You just can’t really [sic] the study like this.”

Snip –> Regional Vehicle Miles Traveled are likely to increase “if gentrification results in a reduction in the population living near rail.” Between 2000 and 2012, while the rest of the city population rose, the Mission lost 4.8 percent of its population, median income increased by 48 percent (gentrification), and households with cars rose from 37 to 64 percent. <—

Comment: You picked the dates when almost nothing was built in the Mission. For instance, the net gain in housing units in the Mission in 2011, according to the Housing Inventory Report from Planning was NEGATIVE 13. Part of this was 2 financing crunches, part was developers waiting for the Eastern Neighborhoods plan to be finished. During that time, as prices went up, and some change of habitation out of rent-controlled units occurred, some larger households were replaced by smaller, presumably wealthier ones.

In fact, there was so little development completed in the Mission during that time, that this can be viewed as the control group for what will happen ABSENT new development. In terms of CEQA what you are really proving here is that NOT DEVELOPING could cause the population to go down and increase VMT. THis is virtualy the opposite of the point you intended to make.

Why don’t you take a look at the studies the UK government just did in Islington, a neighborhood in London where 70% of the residents bike to work? That might blow up your cozy little “If-we-build-it-they-will-come” consensus. However, I doubt anyone in the planning department will be swayed by, you know – actual facts. That department, indeed most city department, are run on adherence to ideology and dogma, facts don’t come into it.

I myself know what to think of such studies… because I’ve never seen one, and I work in this field. It might be true in certain circumstances, but I doubt it’s ever been studied on a neighborhood by neighborhood basis, longitudinally, with before-and-after testing.

I wonder what Tim think of studies showing that the more bike lanes you pack into a neighborhood, the higher that neighborhood’s CO2 levels rise – because autos sit longer in traffic or circle looking for parking and thus belch out far more CO2. SF’s program of removing parking and traffic lanes to add bike transit is actually going to blow our CO2 emissions through the roof.

Thanks, I was looking for the census tract numbers. I will try from the map but it is not all that clear.

There is a color-coded map on page 68 that shows TOD tracts they define as having gentrified.

It would be interesting to see the specific census tracts they say are gentrified and displaced. I could not find the source data in the report.

They have a complicated set of criteria set forth on pages 65-67. The criteria are slightly different for LA and the Bay Area.

They also evaluate loss of low-income housing (page 71) and loss of low-income households (page 74) as proxies for displacement.

And what is displacement?

How did they define a gentrified census tract?

I have not read the study but concluding cause and effect from correlations is dangerous. I would say increasing prices cause development, not the other way around.

And peninsula employees caused the Google buses not the other way around. There are no data showing that Google buses have anything to do with “displacement.” A Google bus stop can be moved, unlike a BART stop.

That transit village in Walnut Creek is occupied mainly by young adults and very few school-age children. Nearly half don’t work in Contra Costa County, and the majority get to work by car. 26% use transit.

This is an incredibly misleading gloss on the report. If you actually read the analysis, you’ll see they define “TOD” as “any census tract within 1/2 mile of a rail station.” See, e.g., pages 50-52. The analysis then compares displacement in those “TOD tracts” to non-TOD tracts. It says absolutely nothing about the effect of new transit infrastructure or new market-rate housing–to the contrary, the report found virtually no connection between new housing and displacement:

“Of the 125 Census tracts that gentrified between 2000 and 2013, half (63) were in TOD areas. Yet, the vast majority of these TODs (58) that gentrified did not experience much development. Only five of these tracts experienced housing development, including two subsidy-driven neighborhoods….we find in general that the vast majority of tracts experienced relatively little development during the time period of analysis. In the Bay Area, most development occurred in tracts that did not gentrify”

For a ‘journalist’ of your stature to flatly lie about the findings of an academic paper is pretty shameful.

MEDA and Tim Redmond are misquoting the Urban Displacement Project’s TOD report by conflating the development of rail infrastructure with the development of housing. The TOD report describes many factors, but I think the primary TOD–displacement connection it describes is development of rail infrastructure which, in the absense of sufficient housing construction, encourages high-income people to move into existing communities and displace low-income people. None of the anti-displacement strategies it proposes involves blocking market-rate housing construction. And it identifies gentrification mostly among areas that have had little housing growth (p. 55). On the other hand, for San Jose, “a key to this area’s success at not displacing low-income households seems to be its high levels of [market-rate] housing production” (p. 245). More housing helps, not hurts.

It’s worthwhile to read this section in full (p. 96). It notes that we often should have more upzoning near transit corridors: “First, local governments may not zone for high enough intensity of development to enable developers to profitably build sufficient new housing and non-residential space to offset the demand effect.”And the fact that upzoning creates value is not a reason not to upzone. In the absense of Proposition 13, we could just tax the value of the upzoned land to use for low-income housing developments or vouchers. But given Proposition 13, the solution is to upzone while increasing inclusionary housing requirements, so that much of the created value goes to low-income and moderate-income households instead of increased land costs.