During the Planning Commission’s hearing last Thursday on corporate rentals, Peter Cohen, co-director of the Council of Community Housing Organizations, made a critical point.

“We have a red-hot real-estate market,” he said, “and that leads to innovative ways to use this market.”

In other words: The minute the city finds a way to regulate one type of scam, another one pops up.

And the latest is what are called “intermediate-length” housing deals.

The way it works, the testimony at the commission showed, is that a developer or the owner of a building will enter into a lease not with a human tenant but with a corporation.

That corporation will then sublet the apartments in that building to either companies that need a place to put up new or visiting workers or to other organizations (say, the producers of Hamilton) who need a place for their actors and producers to stay for a few months.

Sup. Aaron Peskin, who is promoting legislation to regulate corporate rentals, agrees that there is a place for this sort of housing, particularly for people in the arts.

But right now, it’s entirely uncontrolled – and apparently, spreading fast.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

A representative of Churchill Living told the commission that her company was leasing new buildings in Mission Bay. “Our clients are tech companies but also hospitals,” she said.

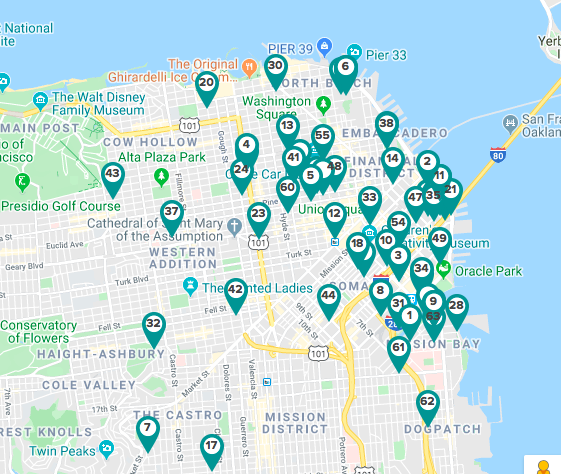

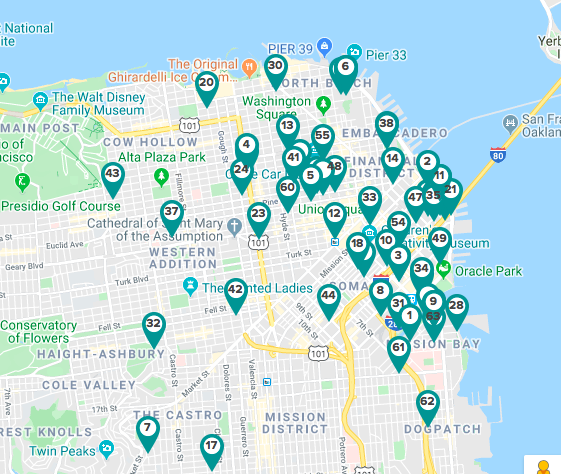

Actually, there are a lot more Churchill Living units in San Francisco:

Everyone seems to agree that existing rent-controlled units shouldn’t be turned into corporate hotels. A representative of Express Corporation Housing said his company never uses rent-controlled apartments as intermediate-length occupancy units.

But KPIX found that in at least once case, another company turned a rent-controlled building into these ILOs.

Theresa Flandrich, a tenant advocate from North Beach, testified that a building in her neighborhood with eight units, filled with longtime seniors, had been emptied because the landlord wanted to renovate the apartments. But none of the original tenants came back, she said, and now the place is corporate rentals.

It’s not hard to check on whether buildings subject to rent control are being used as corporate rentals. Just go on the Zeus website.

In about ten minutes, I found five multi-unit properties that were built before 1979 (which puts them under the rent ordinance) that are listed as ILOs. They aren’t just downtown or in Mission Bay – they are in the Mission, the Castro, and the Marina.

Among the properties listed as corporate rentals are units at 108 Bosworth, 3474 17th Street, 825 Post, 61 Diamond, and 120 Union.

These are places that otherwise would be available to people who are struggling to find a place to live in San Francisco.

Then there’s all the property that the city has approved in the name of addressing the housing crisis – that is, new market-rate housing.

It appears, from my research and the Planning Commission hearing, that hundreds of these new units, maybe more, and just corporate hotels.

The city spent years trying to control Airbnb. And the minute we got some decent rules on that operation, this comes along. In fact, Airbnb has its own corporate rental subsidiary.

The rents in these units run as high as $10,000 a month. That’s a lot more money that most landlords could get by renting the property to long-term tenants.

Myrna Melgar, the Planning Commission president who is now running for D7 supe, said that she fully supports regulating these ILOs. She made the point, which Peskin agrees with, that there’s an issue for the arts – and the legislation would allow ILOs, just limit and regulate them. Then she asked a bizarre question about “financing for new projects,” and whether developers might need ILOs as a bridge before a place is fully rented. There is no issue with vacant market-rate units that can’t be rented; the vacant units are ones that are held off the market by speculators or, it turns out, waiting for corporate rental clients.

The commission, claiming it needs more information, voted to continue the issue for two weeks – at which point, since Commissioner Milicent Johnson will be out of town, Commissioner Dennis Richards is on leave, and Commissioner Myrna Melgar is stepping down, there may be only four people to hear this critical issue.

The Commission, such as it is, will hear the department’s budget requestThursday/23, and it’s worth mentioning because it shows one of the reasons the city does so little actually planning.

The budget for the department for next year includes $61.8 million in revenue – and $44.9 million of that is fees for services. That is, 72 percent of the department budget comes from fees paid by developers.

That means the primary mission of the department has to be facilitating development; if there aren’t a lot of big projects paying big fees, the department can’t pay its staff.

The city’s General Fund provides only $7.8 million – about 12 percent of what it costs to run the department.

No surprise: The largest contingent of planning staff – 75 planners or 32 percent of the entire workforce – is devoted to “current planning,” which means, in essence, permit processing and managing permit processing.

The department will have only 23 planners devoted to future citywide planning in the areas of housing, community equity, transportation, and land use and community plans.

That’s why when you go to Planning Commission hearings you constantly hear community advocates saying that there is very little planning going on, and a whole lot of catering to developers.