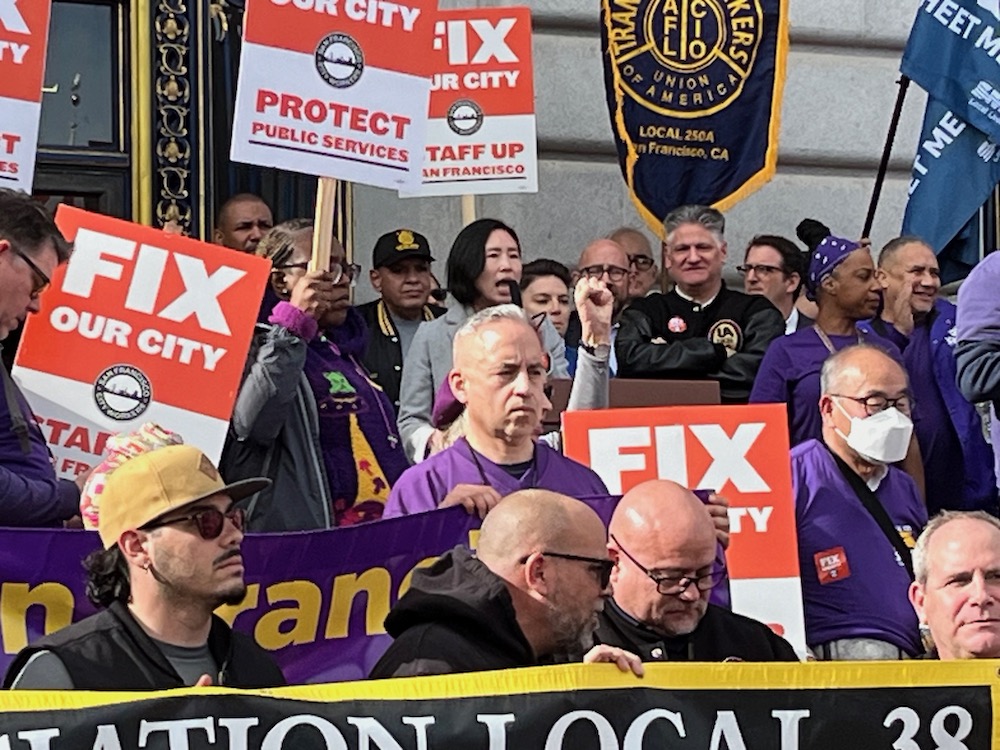

While the Mayor’s Office was presenting the bleak news to the Board of Supes Budget and Finance Committee, hundreds of union members and their allies rallied in front of City Hall to demand solutions that aren’t based on deep service cuts.

“The answer to all the questions about making the city work is to hire more city workers,” Kim Tavaglione, executive director of the San Francisco Labor Council, told the loud and boisterous crowd.

The city currently has 3,700 vacant positions; crucial services like the 911 call center are radically understaffed. “We want to make the city safe, but the city won’t let us hire people,” Burt Wilson, president of the SEIU Local 1021 911 workers chapter, said.

The mayor’s response to a looming budget deficit has been almost entirely demanding cuts to agency budgets—and primary to city workers. She has told departments not to fill vacant positions unless they are “essential.” (Nurses, 911 dispatchers, health-care workers, social workers, public works employees, and many others are apparently not “essential.” Cops are.)

The Department of Public Health budget, which includes SF General Hospital, is $2.3 billion. Cut ten percent of that and you’re losing $230 million, almost all of which goes for essential services.

Among the things on the cutting block: A tiny $200,000 allocation to help at-risk and homeless youth buy food. It’s going to get way worse.

I spoke to Rudy Gonzalez, the secretary-treasurer of the Building Trades Council, and asked him what labor’s alternative is.

“The alternative is sitting down with the public employees to prioritize the human infrastructure,” he said.

He also said that labor will be looking at how much money San Francisco spends on outside contracts for work that could be done cheaper by city workers. It’s a big number; the unions say the city awards $6.2 billion in private contracts every year, the vast majority to companies outside of San Francisco. A lot of that is enterprise departments like the Airport and the Port, but there’s at least $1 billion in outside contracting in the General Fund.

Again, some of that is not only fine but cost-effective: It’s way less expensive to contract with the Eviction Defense Collaborative and Legal Assistance to the Elderly to provide lawyers for people facing eviction than to set up an entirely new city department staffed with city lawyers to provide that service.

A lot of human services nonprofits do an amazing job at a relatively low cost; in fact, a lot of unionized nonprofit workers on city contracts make substantially less the city employees, which is another entire issue.

But what the labor folks are talking about is private, for-profit companies who are charging the city large sums for services they say could be provided in-house. Two examples they offer:

A $4 million IT contract was awarded to Auriga Corporation, which is based outside of SF. Their hourly billing rates are as high as $346 per hour for work that could be performed through filling staffing vacancies.

In a contract awarded to Cross Country Staffing for $85 million, it cost taxpayers 14% more for contracted nursing services than had the city filled in current nursing vacancies. Providing in-house nursing services would have translated to around $1.8 million in cost-savings for a single year.

Sup. Connie Chan, who chairs the Budget and Finance Committee, told the rally that “the city doesn’t work because we don’t support our workers … As your budget chair, we will stop the top-down approach and listen to the workers.”

In a press release today, Chan called for

Contract accountability: Currently the City has granted billions of contracts every year, we must evaluate their performance and service delivery and terminate wasteful contracts; Maximize government performance and efficiency; no one-size-fits-all approach to staff management. Review and reduce the city’s operational redundancy: we can reduce top-down bureaucracy and redundancies through consolidation.”

At the rally, she called for an end to “tax giveaways to billionaires,” a point she also raised at the hearing today.

She mentioned the mayor’s expensive efforts to reward APEC visitors, and “tax exemptions for parts of downtown,” but said that it appears those strategies haven’t worked. “How long should we evaluate and determine what is not working?” she asked.

But there’s another issue that is looming, and will have to be part of the discussion: How does San Francisco replace the revenue it lost from the failed policies of relying on downtown for our economic future?

What new sources of revenue—yes, that means taxes—can the city use, and can we create a new system that is more fair and progressive for everyone?

“New revenue sources have to be on the table,” Gonzalez told me.

There’s not a lot of time before the November ballot, and any significant changes in the city’s tax structure would almost certainly need to be approved by voters. I don’t see anyone at City Hall seriously convening the task force of city finance experts, labor, community, and business to talk about a way to bring in a few hundred million more dollars a year—while reducing the burden on small businesses and poor and working-class people.

Unless we are going to slash and burn the budget, that has to start now.