At some point, humankind will look back and figure out what to make of our heavy usage of psychedelics at music festivals. Despite the fact that mega-events provide what probably constitutes the worst atmosphere for astral introspection, many people’s first mushroom or acid trips still happen at mobbed festivals — or maybe the hardest trip they’ll ever trip will take place at one. Hello, 21-year-old me at Reggae on the River. (I am not ashamed.)

The ritual of ingestion is often articulated in traditional cultures by a shaman — or a guide well-read in the ways of certain substances. But in contrast with ayahuasca ceremonies, at Coachella or Burning Man psychedelic use is presided over by musicians on a stage set thousands of people away — or by a friend who is just as dehydrated and medicated as you are — or no one, when a overpowering wave of crowd splinters a crew.

Lacking a safe container to trip in, psychedelic complications are bound to happen in the haphazard setting of festival madness. Psychedelic users who become violent or otherwise unresponsive to official suggestion via a difficult trip can wind up at the hospital or worse, jail. Neither place is likely to alleviate the paranoia or fear they’re experiencing.

Drug research and education organization MAPS (Multidisciplinary Association For Psychedelic Studies) stepped into this disconnect when it raised the first incarnation of its Zendo Project at Burning Man in 2012. The on-site counseling program complimented MAPS’ larger mission to advocate for the therapeutic uses of psychedelics. The group’s work often focuses on the way that drugs can be used to open up healing emotional pathways, such as a 2016 study that looked at the effects of MDMA on people suffering from PTSD.

“The term psychedelic means ‘mind manifesting,’ which means that our conscious mind becomes aware of subconscious things,” says Sara Gael, MAPS’ director of harm reduction and Zendo Project organizer who has been involved since the year the program came to life and is a firm believer in the benefits associated with responsible usage of the drugs. “That’s what therapy is about, exploring the subconscious and the aspects of self that society has taught us to repress.”

In the uncertainty of festival chaos, worries about personal sanity or safety can complicate a psychedelic trip, rendering it all but impossible to stay open to the painful realizations that psychedelics can trigger. The Zendo’s infrastructure responds to this construct; volunteers erect a tent where triggered festival attendees can rehydrate, lie down, and/or snack, in addition to connecting with trained souls ready to sit with them through any threatening visions or panic-inducing paranoias.

“Some of the more challenging cases we experience are people who are really frightened, who might then become aggressive, or try to run away, or feel really lost or paranoid,” says Gael. “Those are some of the more difficult situations to work with because we’re trying to keep that person physically safe. That’s why we work in collaboration with medical and security.”

Today, the Zendo Project has helped 2,900 people at large events, teaming up with security and medical festival staff so that attendees receive the best treatment for their particular situation. Given the project’s success, it is pleasant to imagine a larger diversity of gatherings in which Zendo-like harm reduction efforts were present. Currently, the program is limited to Burning Man and its regional events from South Africa to San Diego, in addition to the other “transformational” endeavors (Lightning in a Bottle, Costa Rican yoga and spirituality fest Envision.)

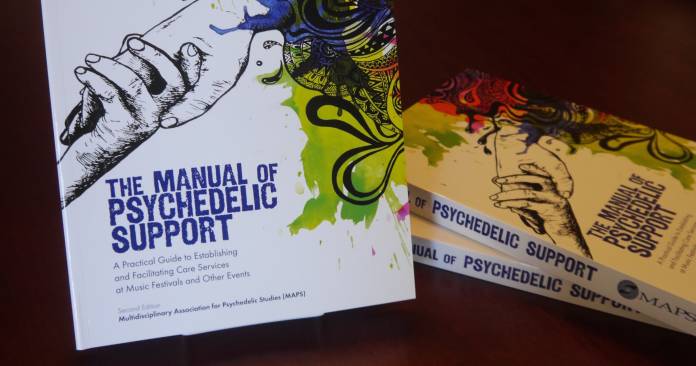

The Zendo Project is looking to expand, and is currently in the middle of a fundraising drive. And MAPS just published The Manual of Psychedelic Support, a thick tome available for free download.

The manual outlines the logistics behind setting up a Zendo Project-like space, not to mention the inclusion of a fascinating history of harm reduction in modern Western festival culture (the original Woodstock festival’s Hog Farmers, founded by Wavy Gravy, are considered pioneers in the area) and the Zendo Project’s guiding principles for interactions with those on tough trips: “creating a safe space, sitting not guiding, talking through and not down, and difficult is not the same as bad,” in Gael’s summarization.

Gael is quick to note that the core principles can even be self-applied, if you can remember them should you enter into a difficult trip yourself. When asked for a couple quick pointers for those finding themselves on shaky psychedelic ground, she ventured: “What is coming up, try to turn into it rather than away from it, because what we resist, persists. Try to find a safe space away from noise with people that you trust. Find someone who is able to sit with you even if they’re not formally trained, who is not freaking out. Trying to connect with your breath and body, connecting with nature can be really helpful, finding a tree.”

She adds that if you’re still feeling shaken up even after you’ve become sober, MAPS has published a list of therapists who are educated in psychedelic integration, or the practice of connecting the dots between psychedelia’s half-processed self realizations.

It is clear that modern day Western society takes psychedelics under much different circumstances than the cultures that previously utilized the substances. The ritual of loading one’s car up with friends and alcohol en route to Electric Daisy Carnival has little in common with the temazcals and sacrament of a Navajo peyote ceremony.

MAPS makes it clear that as part of a harm reduction strategy, the Zendo Project “simply responds to the reality that this is the current situation, says Gael. “And that despite policy, [psychedelic usage] is going to continue.” After nearly 50 years of practice, however, new forms of psychedelic guidance in certain modern day sites of cultural ritual are being developed — a nascent safety net for the psychedelic voyagers of today.