Thanksgiving is traditionally a time to reflect on good things already received—admittedly a task 2020 has not made easy—and movies this weekend are cooperating with that sentiment by primarily looking backward. Roxie Virtual Cinema is offering a new restoration of the 1965 Nouvelle Vague hootenanny Six in Paris (more info here), which tasked a half-dozen directors of that school (including Godard, Chabrol and Rohmer) with creating short segments about a particular City of Light neighborhood for one omnibus feature.

The Roxie is also participating in a de facto if coincidental celebration of Asian cinema in various forms via an online revival of Fruit Chan’s 1997 Made in Hong Kong (more info here), an energetic low-budget crime comedy and “punk tragedy” that has the distinction of being the first independent feature produced after that city (or “special administrative region,” as the mainland Chinese government prefers) was officially handed over by its erstwhile colonizer Britain.

Also heralding new voices and directions in Asian moviemaking around that time was the next year’s Flowers of Shanghai by Hou Hsiao-hsien, who led Taiwan’s own New Wave to international acclaim in the 1980s and 90s. (He’s considerably slowed down since, with 2015 marital arts extravaganza The Assassin his only feature in the last thirteen years.) Consisting of 38 long shots separated by blackouts, this intricate period piece set in the late 19th century portrays intrigue of love and money between several high-end brothel courtesans and the men (notably Tony Leung) who are their besotted and manipulated clients. Located entirely in handsomely decorated interiors, with the “flower girls’” colorful silks lit by the golden glow of oil lamps, it’s an ornate if discreet drama whose 4K restoration has just joined BAMPFA’s streaming menu (more info here).

Two pioneering Asian-American screen legends are also paid homage in new documentaries. Tonight, Fri/27, drive-in venue Fort Mason Flix is showing Be Water (more info here), on what would have been its subject’s 80th birthday. Bao Nguyen’s ESPN-produced feature chronicles the regrettably short but highly influential life and career of Bruce Lee, the San Francisco-born martial arts superstar who died abruptly in 1973 at age 32. While Lee had to return to his parents’ Hong Kong to fulfill his screen potential after hitting a glass ceiling in Hollywood, those limitations had already been mapped by the Chinese-Americam luminary paid homage in Searching for Anna May Wong, now available for streaming on AsianAmericanMovies.com. Though Wong was also sorely disappointed by the roles Hollywood offered her, she nonetheless blazed a trail with numerous striking appearances in films of the 1920s and 30s.

Finally, BAMPFA, Alamo Drafthouse and Rafael@Home (as well as available physical theaters) are all adding Bill & Ted actor turned director Alex Winter’s Zappa. Billed as the “first all-access documentary” about the late musician (prior attempts have been compromised by disputes amongst his family heirs), it chronicles the life and times of a composer, performer, and multimedia artist who brought the avant-garde to rock audiences, and vice-versa. Frank Z. may himself be gone, but his fan base is not: This film reportedly set a crowdfunding record on Kickstarter.

—–

Seemingly not looking backward at all is another native SF son, Clint Eastwood, who turned 90 six months ago and is reportedly in the middle of directing and starring in a new movie. That is not unprecedented (Portuguese director Manoel de Oliveira stayed active behind the camera until he passed five years ago at 106)—but it’s certainly impressive nonetheless. Kino Lorber has recently released a slew of vintage Eastwood titles that illuminate his early steps from popular but critically disparaged stardom to eventual status as an industry institution, and a sort of sub-industry in himself.

He started out as a contract player at Universal in the mid-1950s, where minor roles in B movies led nowhere until he was cast in the broadcast series Rawhide, a long-running hit. When it finally petered out, he accepted an offer (after others had turned it down) to star in an unpromising low-budget Italian western for a little-known director. But Sergio Leone’s 1964 A Fistful of Dollars ignited the whole “spaghetti western” vogue, reviving the genre, and making Eastwood a huge European star—even if it and its “Dollars Trilogy” followups (For a Few Dollars More, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly) didn’t reach the US until 1967.

Despite that delay, he returned a hot item, and was immediately rushed into several major-studio vehicles: Hang ‘Em High, a western that many then considered better than the Leones (though no one would make that claim now); proto-Dirty Harry urban thriller Coogan’s Bluff, directed by frequent future collaborator Don Siegel; Where Eagles Dare, a WW2 epic; and Paint Your Wagon, one of several ruinously expensive musical flops made in the wake of mega-successful The Sound of Music. Eastwood was appalled by the wastefulness exhibited on the latter two big-budget endeavors. But by then he’d already founded his own company. Nearly everything made by Malpaso Productions would come in under-schedule and under-budget—something kept him a relatively safe bet amongst the studios to the present day, despite occasional commercial duds.

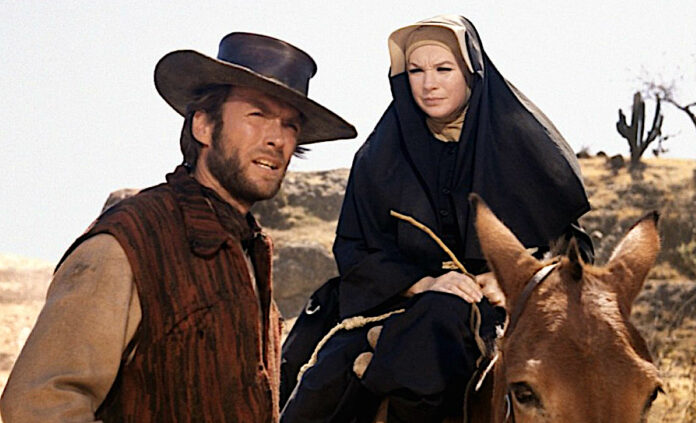

The first of the new Kino releases is Two Mules for Sister Sara, which Siegel directed, and for which Clint took second-billing—something that wouldn’t happen again for a long time, particularly as neither man enjoyed working with top-billed Shirley MacLaine. This western is mostly comedic (at least until the climactic bloodbath), hinging on an early version of the classic Eastwood dynamic in which women mostly exist to imperil and/or exasperate him. In this case he’s a lone gunman who rescues a nun from rascals in the desert, then finds he’s stuck with her—and that she has a somewhat unusual (for her alleged vocation) relationship to salty language, whiskey, and Mexican revolutionaries. This leisurely (a little too much so in the two-disc Blu-ray package’s longer “international version”), spaghetti-ish spin on The African Queen was only a moderate success.

After another war epic, Kelly’s Heroes (the last film he made without Malpaso’s involvement), Eastwood took another gamble on femininity with the Siegel-directed The Beguiled, in which he’s a wounded Union soldier hidden—and fought over—by a houseful of Confederate women. Rendering its hero helpless, this 1971 Southern Gothic did not appeal to his fanbase, but remains an interesting stretch that would prove superior to Sofia Coppola’s disappointing 2017 remake.

For his own directorial debut that same year, he perhaps surprisingly chose another tale of masculinity panicked by kwazy wimmens: Play Misty For Me, a precursor of Fatal Attraction in which his radio DJ enjoys a one night stand, only to discover this “no strings” hookup indeed has strings—talons, even—as formidable woman-scorned Jessica Walter runs a fast gamut from possessive to suicidal to homicidal. Shot on the future mayor’s home turf of Carmel, Misty is a very good thriller, showing that Eastwood had absorbed a great deal from the directors he’d worked for.

His next was another Siegel joint, the SF-set Dirty Harry (which is not among the Kino releases), a somewhat reactionary cop thriller that was so successful the star made four sequels over the next 17 years. He then clocked two more westerns: The 1972 Joe Kidd, a mediocrity on which he clashed with director John Sturges (who was on a boozy career eclipse a decade after mega-hits The Magnificent Seven and The Great Escape); and the following year’s High Plains Drifter, a better black comedy-cum-allegory in which Eastwood (as both actor and director) expanded on the spaghetti template.

A sort of nastier High Noon, the latter has his lethal “Man With No Name” hired to get a town out of trouble. Instead, he takes them on a bad trip, complete with literally painting the entire town blood-red in preparation for a final comeuppance that punishes not just the official bad guys but all the upstanding-citizen hypocrites. Around this time, Eastwood proposed to John Wayne that they make a film together. The Duke wrote an angry letter back saying how much he loathed violent, cynical Drifter (he’d hated High Noon too, for that matter), which put the kibosh to that idea.

Branching out, Clint directed the first movie in which he did not star, also probably the most obscure title in his canon: Breezy, shot in 1972 but unreleased until the end of 1973, at which point it seemed even more outdated. Kay Lenz plays the titular figure, a teenage hippie who tumbles onto the path of middle-aged, divorced real estate agent William Holden and won’t go away until he also feels the Luv coursing through her taut young body. This Manic Pixie Dream Girl prototype is like a puppy, unruly but adoring and adorable, as well as clothing-resistant. The May-December “now romance” was poorly received then, and today is pretty much unwatchable.

Back on commercial terra more firma, Eastwood followed that flop with the first Dirty Harry sequel (Magnum Force) and 1974’s Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, a crime caper from writer-director Michael Cimino (later of The Deer Hunter and Heaven’s Gate) that stirred no great enthusiasm at the time. But now it looks as good as anything the star did in the Me Decade.

The new Kino releases skip those two (they did re-issue Thunderbolt last year) for 1975’s The Eiger Sanction, which the director-star purportedly did to get out of his Universal contract, and because he wanted to go mountain climbing. There is indeed some great climactic Swiss Alps footage in this espionage tale, but the film runs an awkward gamut from supervillain cartoonishness to straight thriller. Its loutish humor also indulged its maker’s (and audience’s) worst tendencies, with rape jokes, a mincing gay bad guy (played by bisexual actor Jack Cassidy), and African-American actress Vonetta McGee as eye candy named Jemima.

None of which came as a total surprise—Eastwood’s movies throughout this period had consistent elements of homophobia and misogyny—but Eiger was noxious even by his standards. Though Eastwood remains a famous Hollywood conservative, it must be said to his credit that later projects as diverse as Bird, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil and Million Dollar Baby made it clear his social attitudes have, mercifully, evolved.

In any case, watching these early 1970s Clint Eastwood films provides not just a overview of a talent’s development, but also a reminder of what audiences were really watching half a century ago. We like to think of that era as the golden age of “New Hollywood,” full of creative risk-taking. But a few well-remembered exceptions aside, the more envelope-pushing movies weren’t what scored at the box-office. Instead, ticket-buyers continued lining up primarily for films that delivered relatively “old-fashioned” entertainment, albeit often with ramped-up violence. And for that mainstream jones, no ascendant star delivered the goods as reliably as Clint Eastwood.