A complete and honest version of “The Lehman Trilogy” (through June 23)—the superbly staged, fabulously performed, very questionably written saga of the family behind banking behemoth Lehman Brothers—would include the story of the unhoused person huddled on the sidewalk that ACT patrons encountered afterwards, barely able to ask for a dollar, a pyramid of detritus piled up before them. The tragedy continually unfolding on our streets was launched into hyperdrive when the “housing bubble” burst apocalyptically in the late 2000s, its inflation a crime against humanity that can be laid directly at the feet of subprime mortgage lenders and bundlers like Lehman Brothers, the precariously leveraged investment bank which in 2008 became the largest corporate failure in US history, taking millions of households down with it.

That person’s story is the real tale of the Lehman Brothers legacy, and one that would never get the lavish, hyper-creative stage treatment that brought “Trilogy” instant acclaim when the current version debuted at the National Theatre of London in 2018 and transferred to New York’s Park Avenue Armory, garnering eight Tony nominations. We’re still waiting for the brave, connected playwright who can materialize that truth without drowning in feel-good, do-nothing liberal pieties or browbeating stereotypes. Perhaps the inspiring collective example of Theater of the Poor can lead the way.

To be fair: By the time of the bank’s spectacular collapse, the Lehman family, who founded the operation in 1847, was long out of the picture. “Trilogy” is mostly concerned, in the first part, with the German brothers who originally landed on the extraction-primed shores of America, led by Henry (John Heffernan, incredible)—”a circumcised Jew with only one piece of luggage”—who set up a dry goods store in Montgomery, Alabama and was soon dealing in fabric made of cotton produced by the nearby slave plantations. He was quickly joined by Emanuel (Howard W. Overshown) and Mayer (Aaron Krohn), and the fabric business expanded to the North, where, it’s quickly observed in wonder and exculpation, “the laborers are paid.” (The brothers themselves enslaved people for 20 years. The reasons the play does not directly address this are nebulous.)

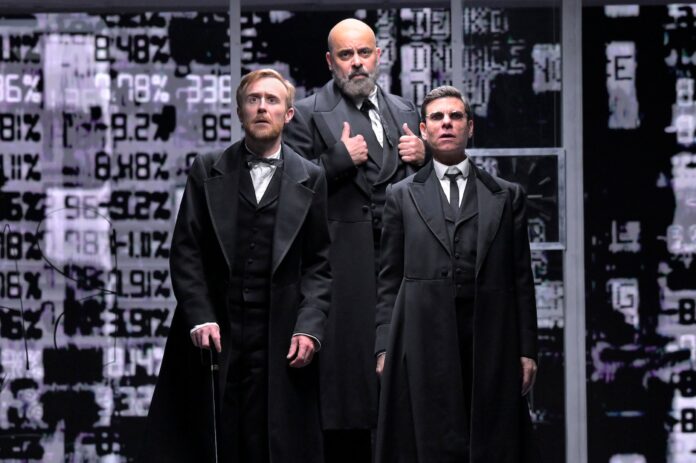

The story of the Lehmans is told breathlessly on an ingenious and gorgeously lit revolving box stage (Es Devlin: set, Jon Clark: lighting), with pianist Rebekah Bruce’s silent movie-like accompaniment adding to the theatricality. The trio of actors brilliantly riff off one another’s lines and perform evocative impressions of the people in their lives, including future wives (though thankfully not slaves), as they gradually assimilate and, later, slip into the Jewish upper crust of New York City. They play all the speaking characters throughout, transforming themselves seamlessly into a plethora of characters from the vivid story.

As imagined by Italian playwright Stefano Massini, star director Sam Mendes, and adapter Ben Power, the brothers are by turns funny, loving, crankish, and deeply traditional—we are caught up in their story as if in an epic novel. But we are also in very morally icky waters from the start, and I’m not sure that leaning heavily on the Jewish heritage of the characters is the right way to balance that out. While things like religious observances, playful Yiddishisms, and old-country melodies do much to humanize the brothers, it’s hard not to bristle at the occasionally full-blown stereotypes onstage, especially right now. “Oh great, a three-hour play about money-grubbing Jews” is how a Jewish friend put it going into the theater. That’s definitely one way of looking at it, unfortunately.

And yet, as the story expands to succeeding generations (cold financial savant Philip, New York governor Herbert, dissipated playboy art collector Bobby), and the business expands to first dealing as a middleman/brokerage for exports as varied as cotton and tobacco, and then making a great leap into railways, Hollywood, the Panama Canal, banking, and the stock exchange, we get a front-row education on the history of capital expansion in the US itself. It’s valuable if incredibly one-sided: the wrong side.

As much as Mendes and co. want this story to be about the “American Dream” and a clan of DIY boot-strapping immigrants making it in the New World (they were in fact from a comfortable cattle-merchant family in Bavaria), it is indeed about the money that flowed through privilege and connection. Anti-semitism barely raises its head—its more virulent public American forms were still incubating while the brothers thrived in the relatively closed Jewish circles of 19th century New York—but that doesn’t mean it didn’t exist outside the ballrooms and mansions of Manhattan. We never see it, though.

And that points to the void at the center of the play: There is no conflict, no tragic antagonist to be overcome—other than death and the whims of the market, both of which will win out every time. A long passage of the play (much longer than the part about the 2008 collapse) deals with the Great Depression, and how Lehman Brothers barely survived it: We are told the names and stories of the stockbrokers who began leaping from the New York Stock Exchange roof while the markets crashed. It’s an affecting gambit, and also feels exploitative. Why do we suddenly care about these “littler” people, and why them more than the millions soon to be starving on the streets, who aren’t even mentioned at all? The Great Depression was a really tragic time… for Lehman Brothers, seems to be the message.

After the care taken with the family’s stories, the final part whizzes through the post-Depression 20th century (the play was condensed from an original five-hour running time to three for the National Theatre debut), a giddy trip through cynically concocted and ill-regulated financial instruments and corporate acquisitions that made a few people enormously rich and caused misery to many, many others. When 2008 hits, a final, striking tableau again uses workers as an emotional device. It’s devastatingly effective, especially if you lived through those times and recall the images from the news. But again, ultimately hollow: We barely even see the workers’ faces, let alone hear their voices.

Because the performances are so technically exhilarating, the historical arc so vast, and the pace so whirlwind, it’s easy to get taken up in the in the play’s sheer momentum and velocity. In the end, however, it’s like one of those thrill rides that has you gripping your seat while it’s happening, but afterwards you find yourself asking “Well, what was the point of all that?” And then you rifle through your pockets for some bills to give the desperate person sprawled out on the concrete before you.

THE LEHMAN TRILOGY through June 23 at Toni Rembe Theater, ACT, SF. More info here.