From ‘Chinatown at Midnight’ to ‘Dangerous Blondes,’ the I Wake Up Dreaming series showcases rare noir films, Thu/6-Sept. 3.

SCREEN GRABS Elliot Lavine programmed his first noir series at the Roxie nearly a quarter-century ago, not long after starting to work as a publicist for that 16th Street cultural institution. The month-long series “included tons of classics as well as a whole raft of Poverty Row obscurities. Most on 35mm, some on 16.” It was a big gamble, but he recalls “the response was overwhelming. Most of the shows sold out, or came close. I followed up with another 30-day festival the following spring.”

Since then, Lavine’s noir series have become a Roxie staple, alongside his equally popular showcases for Hollywood pre-Code features. In recent years he’s expanded the loyal audience’s almost insatiable hunger with schedules of French noirs, international

noirs, and “Not Necessarily Noirs”—the latter covering genre terrain overlapping but not strictly part of the postwar crime melodramas that Gallic admirers retroactively dubbed “film noir.”

But his main event, these days called “I Wake Up Dreaming” (after I Wake Up Screaming, a 1941 proto-noir mystery starring leading WW2 pinup Betty Grable), maintains its fairly strict focus on Hollywood “B” thrillers of the 1940s and 1950s.

This time, however, Lavine will be taking his celluloid tough guys and hardboiled dames a few blocks uptown to the larger, more resplendent Castro Theatre. (Where each January there’s the “Noir City” festival — formally unrelated to Lavine but which owes a great deal to his pioneering model.) Each Thursday night from Thu/6 through Sept. 3 that Art Deco movie palace will host double or triple-bills of 12 variably rare noirs. All are

being shown in 35mm prints (no digital projection), and none, Lavine promises, have ever been shown at the Castro before — or at least not since their original release.

The location shift may surprise some. Lavine — who’s still working with the Roxie, next on a “French Noir II” series in November — says it simply “had to do with economics. These shows can become costly on the front end with advances and guarantees being paid to the studios for the use of their prints. It had become harder and harder to expect the always-struggling Roxie to assume that obligation, making the formation of a meaningful

series that much more difficult. Besides, it just seemed like the time had come to move the show to a different venue.” It’s not his first such move: Lavine has programmed the occasional film event in New York, L.A., Portland and the East Bay, with more such ventures on the horizon.

But noir has been a consistent thread in that career (even before it existed as such), going all the way back to 1976. Lavine had then just moved to SF from Detroit when he experienced a double epiphany: Reading the film-lit classic Kings of the B’s, “a wonderful anthology of film criticism which opened my eyes to the fact that so many of these incredible films existed under the banner of film noir;” and seeing Edgar G. Ulmer’s 1945 Detour, the ultimate expression of noir style and fatalism transcending budgetary limitations.

If decades ago that latter cult favorite seemed the last word in obscure archaeological finds dug up from Hollywood’s factory heyday, the current Castro series includes plenty of titles likely to be discoveries even for the most dogged noir fan. Some have never been released to DVD, Blu-ray VHS. Among them are the SF-set Chinatown at Midnight (1949) and 1943 comedy-mystery Dangerous Blondes, as well as 1956’s Inside Detroit, a tale of racketeers versus automotive union organizers in the Motor City. The latter is paired on August 20 with the equally undersung (but luridly titled) Guns, Girls and Gangsters, a nicely shot 1959 indie thriller with a surprisingly good performance by third-string Monroe-esque platinum blonde Mamie Van Doren as a moll reluctantly pulled into a Vegas heist, then terrorized by future spaghetti western star Lee Van Cleef as the crazy prison-escapee husband she hasn’t been missing one whit.

Second-string Monroe imitator Jayne Mansfield also exerts more dramatic muscles than usual in 1957’s The Burglar, likewise being reluctantly drawn into a heist by Dan Duryea as the brother who likes her a little too much (for a brother). A-list stars of the period made such crime melodramas, too, most received back then as routine “programmers” even if today they look considerably more inspired. A reliable leading man to nearly every glamour queen in Hollywood’s “golden era,” Robert Montgomery directed

and starred in 1947’s Ride the Pink Horse, which despite some phony ethnic “exoticism” and stereotypes may be the best border-town noir predating Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil. Its gringo hero (ironically named “Lucky” Gagin) plunges headlong into a sinkhole of corruption and deception that bears some resemblance to Malcolm Lowry’s lit classic Under the Volcano, published the same year. Though the actual source novel by Dorothy B. Hughes had to be toned down for the screen, its hell-on-Earth cynicism remains startlingly present.

Other relatively mainstream star-driven studio releases in the current “I Wake Up Dreaming” edition include Witness to Murder (1957), in which Barbara Stanwyck plays the title figure (but nobody believes her); and Jacques Tourneur’s 1957 Nightfall, with Aldo Ray and Anne Bancroft (in nearly the last role of her early Hollywood ingenue period) as innocents forced on the lam by a couple ruthless criminals. One of the last great noirs from an already crumbling major-studio system, Nightfall’s 48-hour

narrative window charts a surprising path that sprawls from the genre’s usual sinister city streets to no-less-perilous snowy backroads in broad daylight.

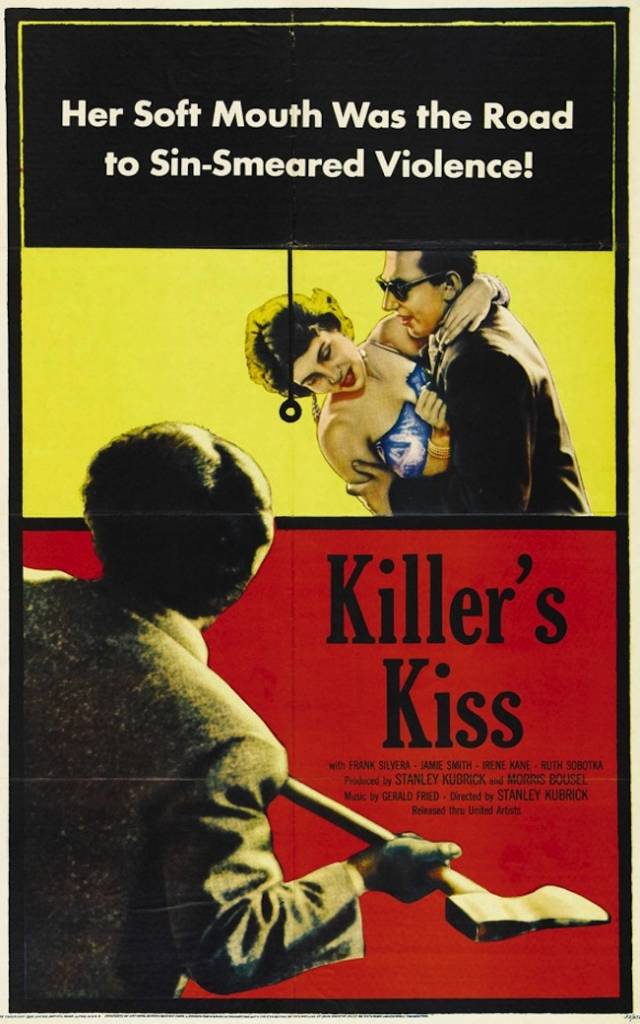

Two of the most fascinating movies in the series, however, were low-budget by even the standards of Poverty Row (the name given Hollywood’s smaller, scrappier production companies), without even the latter’s mini-studio resources. One is Killer’s Kiss,

a 1955 “B” that’s surprisingly little-seen given its pedigree: It was the first conventional commercial feature (1953’s hour-long, arty war drama Fear and Desire doesn’t really count) by Stanley Kubrick. His background as a documentarian and fight photographer

are amply displayed in this simple story of a failed boxer whose fledgling romance with a dime-a-dance girl gets them both in trouble. Occasionally dragged down by banal dialogue awkwardly dubbed in post-production, its fresh atmospherics and often striking

visuals hint at the great directorial career that was to come.

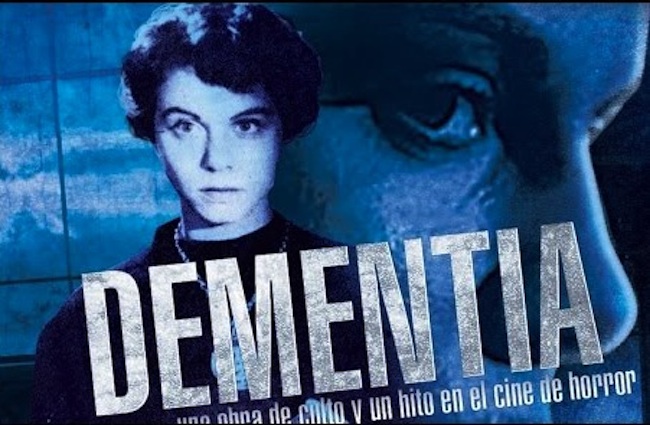

There would be no future body of work, however, for the uncredited director of the same year’s even more bare-bones Dementia, which first gained some cult notoriety years later in a mutilated version released as Daughter of Horror. This expressionist nightmare

has a nameless young woman (Adrienne Barrett) wandering the streets of Los Angeles, where she’s duly pawed by sleazebags (notably one played by producer Bruno VeSota, who later questionably claimed to have created the film as much as one-shot-wonder writer/director John Parker), but is possibly more a menace to them than vice versa.

Is she crazy? Is she homicidal? Are her crimes (and those of others) simply delusions? We’re never sure; this fever dream’s ambivalence heightened by its complete lack of dialogue, its flavorful B&W photography by William C. Thompson (who also shot such Ed Wood joints as Plan 9 From Outer Space), and a suitably avant-garde score by esteemed composer George Antheil. An oddball original, Dementia will be shown at the Castro in its preferred version, without the clumsy “explanatory” voice-over narration that was tacked on after its initial commercial failure.

Showing a film like that at all — let alone in anything close to ideal condition — isn’t easy, and it’s getting harder. According to Lavine, “Many titles, [including those] familiar to most on tape or disc, simply don’t exist any longer in viewable 35mm prints. This is especially true for films now in the public domain.” Dementia is one lucky exception. But there are still plenty of holy-grail noirs Levine is still trying to hunt down, notably VeSota’s own 1956 Female Jungle (with Mansfield) and the 1948 mystery curio The Argyle Secrets. “For me, Poverty Row is the final battleground,” he says. “It’s where the best of the forgotten reside.”

‘I WAKE UP DREAMING’

Film Noir Series

Thu/6-Sept. 3

Check website for dates, times and prices

Castro Theatre

www.iwakeupdreaming.com