With the mess that was the Super Bowl negotiations, and the FBI investigations at City Hall, and a genuine feeling that the mayor isn’t listening to anyone except the tech lords, there’s talk around City Hall of a new political idea:

Maybe San Francisco needs an Office of the Public Advocate.

It’s a position that’s existed for years in New York City, costs only a microscopic fraction of that city’s budget, and offers the public a central place for complaints, suggestions, and oversight.

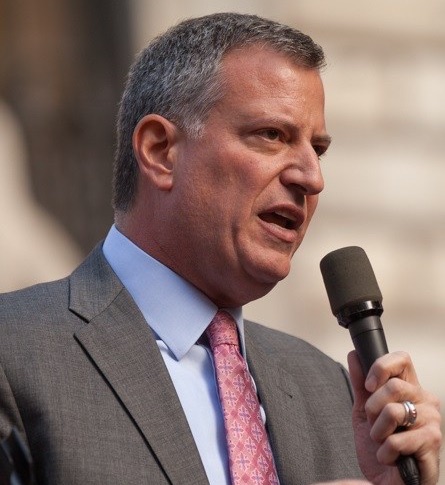

In fact, in NYC, the public advocate is seen as the city’s second-highest elective office, one that Bill De Blasio held before getting elected mayor.

There are lots of ways to look at this. The New York office has its responsibilities; there are others that could be added. But it’s an idea well worth discussing.

There will no doubt be people who argue that city government is already too big, that district supervisors provide all the representation that the neighborhoods need, and that a new office would be a waste of money.

Those same claims were made a couple of years ago in New York, when some said the office – whose budget has been deeply cut – was no longer necessary. Others, however, argue, as attorney Lucas Anderson did in a recent article in the New York Law School Law Review:

These criticisms fail to account for the important role the Public Advocate plays as an arbiter of citizens’ complaints, an independent monitor of government services, and a check on the Mayor’s sweeping administrative powers. Unlike appointed officials with similar ombudsman-type duties, the Public Advocate is able to review, refer, and resolve individual service complaints with the primary purpose of achieving citizen satisfaction, and without regard to the interests of a particular government agency or program. In addition, as a specialized office charged with monitoring government services citywide, the Public Advocate is able to recognize and reveal systemic administrative problems and their causes. Finally, as a “watchdog” over an expansive city government and a counterweight to mayoral authority, the Public Advocate performs essential oversight functions that promote government transparency and accountability.

The entire budget of the New York Public Advocate’s Office is about $2.2 million. If San Francisco spent the same amount, we’d be talking about something like .02 percent of the city’s budget, or less than half of what we paid for security and support services for Super Bowl 50.

The concept has come up in the past – in 2002, then-Sup Jake McGoldrick drafted a Public Advocate proposal, but the controller at the time, Ed Harrington, “came by and told us that he was already the public services auditor,” McGoldrick told me.

That’s true: The controller, under the City Charter, is also supposed to audit the effectiveness of public services. But the controller isn’t an elected official; the job is appointed by the mayor. And controllers have never been visible critics of existing administrations and aren’t widely seen as a place for the public to file complaints. The oversight that the Controller’s Office provides is largely financial monitoring; there’s no unit, for example, that looks at corruption or advocates for better government.

There’s another interesting element of what a public advocate might do that alone could make the entire office worthwhile. That person could take over enforcement of the open-government laws.

San Francisco has one of the most expansive sunshine laws of any city in the country, but it’s been undermined for years by a fundamental weakness: When public officials refuse to release documents or hold secret meetings, nothing much happens.

The Sunshine Ordinance Task Force was created to look into those violations and make findings. The panel holds regular meetings, takes testimony, deliberates and makes findings. But when the commissioners find that an official acted improperly, all they can do is forward that to the Ethics Commission, where the complaints almost always die.

There’s talk among sunshine advocates of amending the law to give the task force more independence, including the ability to hire its own legal counsel. That’s important because the panel is now advised by a representative of the City Attorney’s Office – and often, the City Attorney’s Office is also the agency that advises public officials on whether or not they have to release records.

But in the end, the only enforcement outcome of a task force hearing is a finding of official misconduct on the part of a public official. Ethics has set a very high bar for that: The official in question had to willfully violate the law, and, of course, if they were acting under the advice of the city attorney, it’s hard to argue that the breach was “willful.”

There’s a very different approach that could be worked into the public advocate plan, and it works just fine in Connecticut. That state has a Freedom of Information Commission, which holds hearings on complaints about public access. Its mission isn’t to find anyone guilty of anything, or charge anyone with misconduct; instead, it has the authority to order the release of documents:

Any person denied the right to inspect, or to get a copy of a public record, or denied access to a meeting of a public agency, may file a complaint against the public agency within 30 days of the denial. The FOI Commission will conduct a hearing on the complaint, which hearing is attended by the complainant and the public agency. A decision is then rendered by the FOI Commission finding the public agency either in violation of the FOI Act or dismissing the complaint if the public agency is found not to have violated the FOI Act. If the public agency has violated the FOI Act, the FOI Commission can order the disclosure of public records, null and void a decision reached during a public meeting, or impose other appropriate relief. In many instances, a hearing is not necessary as the parties are able to resolve their differences with the assistance of an FOI staff attorney, who acts as an ombudsman.

In other words, if the FOI Commission says someone improperly withheld records, or held an illegal meeting, the panel has the authority to order that the problem is fixed. When I was at the Hartford Courant many years ago, our reporters routinely went before the commission (no lawyers needed) – and routinely won orders that records be provided, immediately.

That’s what most of us want, anyway – I’m not interested in punishing someone who refused to give me documents. I just want the documents.

So suppose that we took the Ethics Commission entirely out of the picture, and gave the Office of the Public Advocate the authority to review Sunshine Task Force findings – and order disclosure if that’s appropriate? The controller has the right under the City Charter to demand any financial or other records from any city agency for audit purposes. The public advocate could have the right to demand, and make public, any records that should have been made public in the first place.

Right now, there’s no elected official whose job is to advocate for more open government. City Attorney Dennis Herrera, to his credit, has been willing to intervene on occasion when a city official is being recalcitrant and violating the law, but the city attorney also has to represent city officials.

The city attorney and the district attorney are charged with investigating and if necessary taking legal action on allegations of wrongdoing by city officials and employees. But the mandates of those two offices is limited to credible allegations of illegal activity. The fact that something’s wrong, inappropriate, bad policy, or just sleazy doesn’t reach the bar.

Let’s take the Super Bowl deal. Even Sup. Aaron Peskin couldn’t get the mayor to reveal who negotiated this fiasco. There is, apparently, no written agreement. None of that is illegal; it’s just really bad, dumb, inappropriate policy. The supervisors can, and will, request a report from the controller on how much money the city actually took in, but a member of the public can’t request that.

An elected public advocate could have demanded from the start that the interests of San Francisco residents and businesses be represented at the table, that the costs and the terms of the deal be made public up front.

Or take evictions. The mayor has intervened in only a very limited number of cases where unconscionable (if perfectly legal) evictions were taking place. The public advocate could help intervene early, bring attention to tenant issues, and get directly involved in cases where the presence of a high-profile elected official with strong investigative authority could make a difference.

If you think the executive branch of government is running just fine right now, and has been running just fine for years, then you can argue that we don’t need a public advocate. Good luck with that.

It’s pretty clear that a substantial number of San Franciscans are deeply unhappy with the way the city is being run. I can see the voters approving a public advocate in a landslide.

Then, as with all citywide elections, we’ll have to make sure we don’t give the wrong person the job. But again: New York, a liberal city, has elected Republican mayors and pro-business mayors, but has traditionally given the office of public advocate to a progressive.

Worth thinking about.