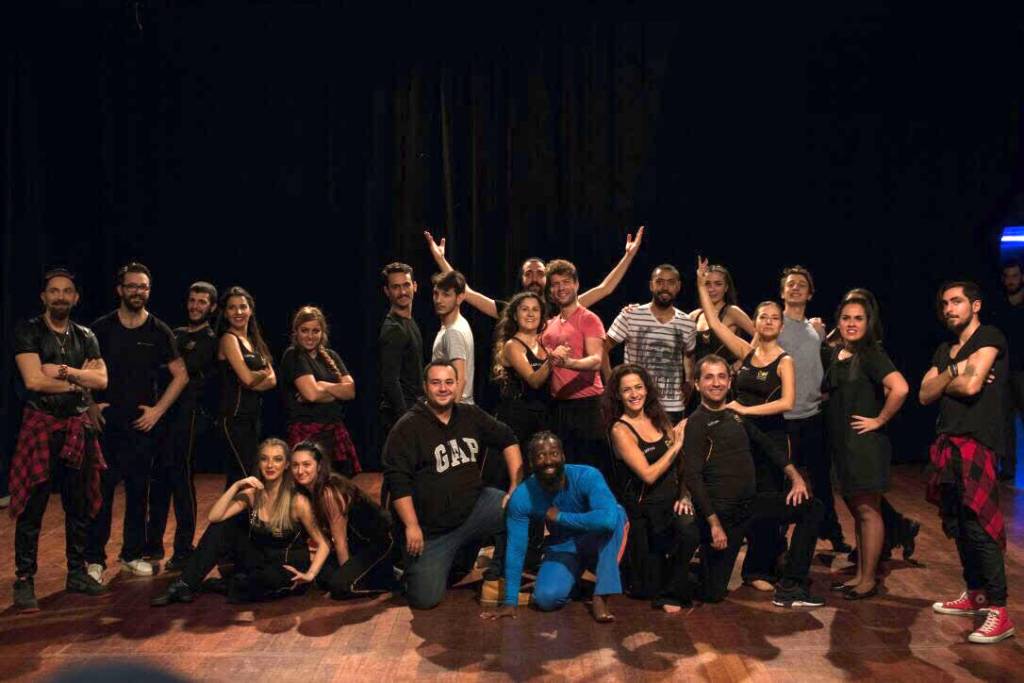

Last fall, dancers from Turkey’s Deaf Dance Academy paid for much of their own airfare to perform Anatolian folk and belly dance in the 2016 edition of the Bay Area International Deaf Dance festival. (The 2017 edition of the festival is tentatively scheduled for August 11-13 — watch for details here.)

“For me and our dancers [the Bay Area festival] was the beginning of something,” wrote Deaf Dance Academy’s director Salim Sinar to 48 Hills via a translator. “Our dancers experienced a different perspective of the world.”

“It’s just not about dance,” says BAIDD festival founder Antoine Hunter. “It’s about expressing yourself, showing your art creatively, history, background, language. We need a platform to present who we are, be heard.” It’s about promoting a cohesive vision of Deaf culture — a mission that is currently being imperiled by the xenophobic actions of the Trump administration.

Inspired by the audiences and respect they found during their stay in the Bay Area, the Deaf Dance Academy returned home to stage their own event in Turkey. Hunter gladly made the trip for opening night.

“The house was sold out,” Hunter remembers. “People loved it and it made … I was one of the first performers to stand up and emcee it, and it made everyone excited to be Deaf, to be who they are.”

The Turkish dancers were not the only international performers at last year’s edition of the Bay’s Deaf Dance Festival. Last year, companies from Costa Rica, Mexico, and England performed, in addition to dancers from across the US.

It is a rough time for US residents committed to international arts programming. The Trump administration’s travel ban against Muslim countries refuses to die. The President’s talk of “extreme vetting” seems to have become de facto policy among border agents, who recently turned away a Canadian set decorator at the border when they found his Scruff gay hookup account on his phone.

Their actions are causing people around the world to think twice about whether a trip to the US is best avoided.

In some places, citizens are encouraging each other to skip trips to the United States entirely. Following the “Adios McAllen” social media campaign south of the border, retail sales have plummeted in the Texan outlet mall border town, where retailers estimate 40 percent of purchases are made by Mexican customers.

Making matters worse, earlier this month multiple artists set to perform at SXSW showcases (which are often unpaid gigs) were barred entry by US immigration officials. Spanish trap artist Yung Beef, Chilean shoegazers Trementina, and Egyptian-Canadian hardcore group Massive Scar Era were denied entry with their B-1 visitors visas.

The rejections were a surprise, and demarcated a shift in immigration policy enforcement. “Artists performing for free at showcase events like South by Southwest have used B-1 visitor visas in the past to enter the U.S.,” reported Billboard. P-1 visas, the legal requirement for visiting athletes and performers, require a $460 application fee, a difficult sum to raise for many independent artists. Hunter says that the Deaf Dance Festival is careful to make sure that participants have professional travel documents.

This year Sinar says that cost, rather than politics, may be the deciding factor about whether Deaf Dance Academy can make the trip to the Bay Area. But the friendly vision of the United States that they brought away from their participation in last year’s festival has been somewhat dispelled by our presidential election results.

“Trump is not welcome in our country, like most other countries in the world,” Sinar says. “His regime is discriminatory and aggressive instead of aggregative. His ideas for Muslim society are also sad. He is the kind of leader who will affect us and the whole world negatively for a long time.”

For the first three years of the Deaf Dance Festival, Hunter was the organization’s sole employee. (He now has one other staff member.) There are other Deaf arts festivals, but as far as he’s aware, his event is the first to focus on hard of hearing and Deaf dancers. He’s constantly looking for new sources of support, donations to keep the work going.

“My festival has made a lot of impact on a lot of people,” Hunter tells 48 Hills in a Skype interview. “I’m not bragging about it — I didn’t think it was going to grow that fast. I thought it was going to grow slowly and get bigger and bigger and bigger.”

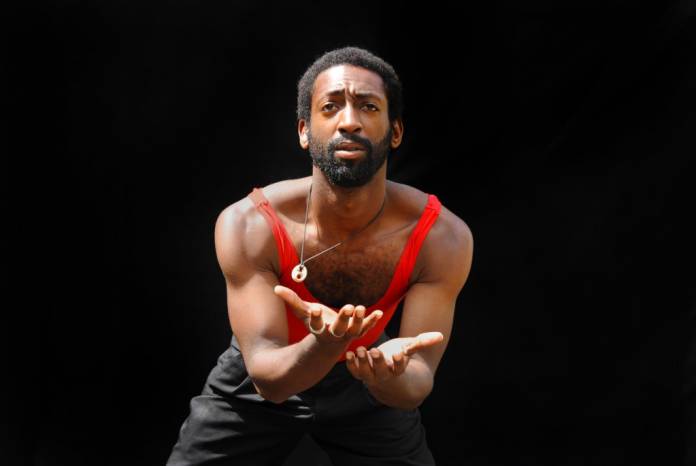

But given the motivation of its lead organizer, the event’s growing significance seems inevitable. Hunter has been Deaf since birth, and was bullied as a teen. He found outlet in physical activity, spending time as an adolescent bodybuilder before discovering the powers of communication inherent in dance.

“I always say, when you can’t express yourself you lose your mind,” he says. “You know, [growing up Deaf] you feel really, really alone.”

An East Bay native, Hunter attended New York City’s Paul Taylor Dance School and danced for a number of companies, founding his own, Urban Jazz Dance Company, in 2007. In 2013, he organized the first year of the Deaf Dance Festival.

He also performs in the festival — this year, his presentation will revolve around human rights violations visited upon the hard of hearing and Deaf in the prison industrial complex.

“They’re often thrown into solitary,” Hunter explains. “Often for weeks or months where there’s no human contact. When that happens, many people lose their minds. No window, not enough air, the bathroom is right there, it gets to the point when someone may lose their sanity. No one wants to talk about it, but maybe if I dance about it, maybe it will start the conversation.”

He sees it as paramount voices from all over the world are represented in the yearly event. This is why Hunter’s organization puts in the work applying for visas and travel arrangements for international artists. “We have Deaf culture in America,” he reflects. “We have Deaf culture in China, we have Deaf culture in Africa. Sign language didn’t just start in France and America. It was already in Hawaii, they had a sign language, their own! It’s really important that we understand our history and background as a Deaf person also.”

Now, he’s concerned that the network he has spent so many years building may be in danger.

Hunter talks about getting documentation from the Oakland and San Francisco court systems that he can bring with him when he greets arriving festival performers at either airport, just in case.

He’s taking precautions not just for the sake of the international performers, but for the health of our culture here in the US. “I think our administration is missing the opportunity to make really wonderful things happen,” says Hunter. “We’re just going backwards. I just couldn’t imagine not having immigrants here. I just couldn’t imagine that.”