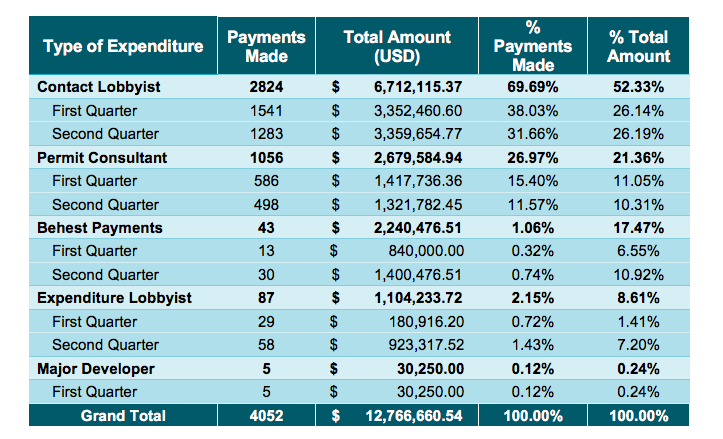

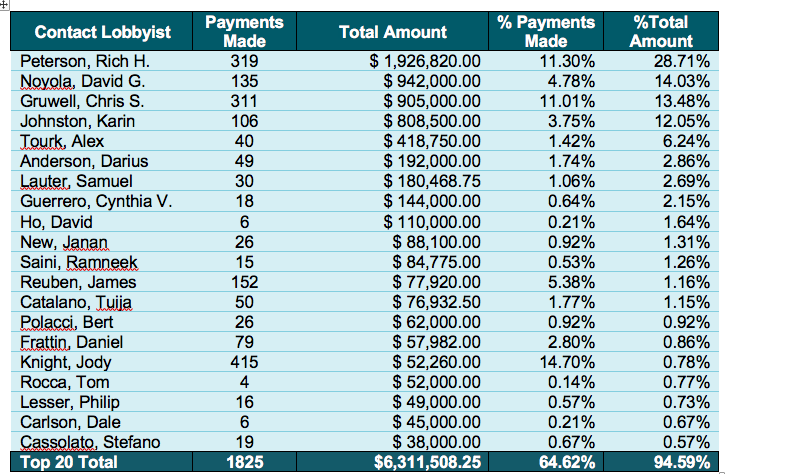

Lobbyists spent more than $12 million seeking to influence San Francisco City Hall in just the first six months of 2019, according to a recent study by Friends of Ethics.

“It’s a first ever look at all of the money trails leading to City Hall, coming from people who want City Hall to act on their behalf,” Larry Bush, the group’s co-founder, told us.

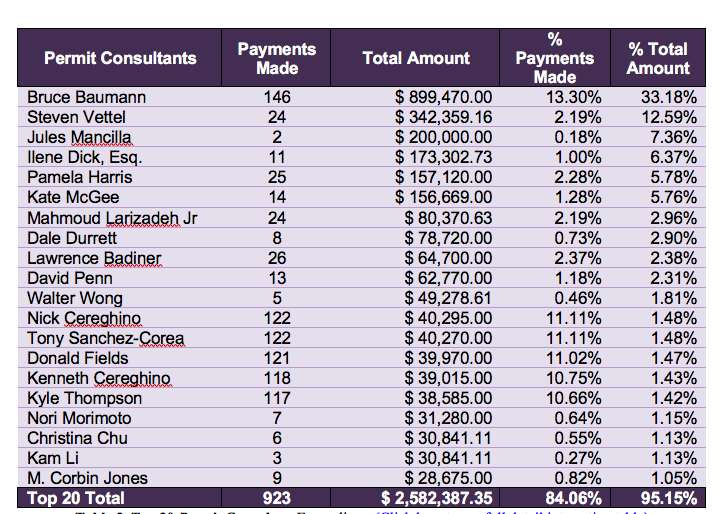

Half of that money went to attempt to influence development decisions, the report states:

Over one million dollars a month was paid or promised to lobbyists and permit consultants or contributed at the request of city decision-makers to influence approvals of land use decisions in the first six months of 2019. This six-figure number does not include campaign contributions to candidates or ballot measures.

The committee argues that it’s critical to track that spending.

“If you look at how much attention we give to campaign contributions and spending, with just the subject of many reviews and oversight, and then you look at what we can find out about money spent to the lawmaking people once they’re in office, you’ll discover that the money spent on lobbying, is four times more than electing people to city offices,” Bush said.

Friends of Ethics is supporting Prop. F, a November ballot measure that would set some new controls over dark money in San Francisco.

The data from the report is just the first half of the year, when five new supervisors took office and Mayor London Breed completed her first year. Spending is projected to at least double in the second half of the year, due to campaign spending, the report says.

“I expect it to increase substantially. First of all, we are going to have reporting now of when an elected official seeks to have their allies contribute towards a candidate,” Bush said. He pointed towards Breed’s support of D5 Supervisor candidate Vallie Brown. “She’s supposed to report any time that she asks for and someone gives her money for Vallie Brown. We don’t see any of that reporting so far,” Bush added.

Bush said he believes that the reason the numbers are so high is due to the fact that there’s so much money to be made with City Hall’s decisions.

“It’s higher, in part because we now have more reporting than we did before, for example we didn’t used to have reporting on expenditure lobbying, that’s people who pay other folks to raise issues at City Hall, and we have over a million dollars in that. And people don’t generally take a look at the behest payments as essentially influence peddling, but it is,” Bush said.

From the report:

Above ground the stream can be followed from lobbyists paid to contact city officials, lobbyists paid to arrange for nonprofits and others to contact city officials, expenditure lobbyists, permit consultants who can help projects obtain permits, major developers and ‘behest’ contributions made at the specific request of a city official to a purpose desired by the official.

As part of the influence system one can track which officials are contacted, whether officials asked and obtained behest payments that were contributed at the direction of officials, as well as travel expenses paid for officials. City supervisors, the mayor and other officials also are required to maintain calendars of their meetings which can be accessed upon a public record request.

But like streams that flow from a distance, only some of it is above ground. In other places it sinks underground out of sight, still ultimately reaching its destination where it can make things flourish. Or it may be damned up to prevent this precious resource from a less desirable location.

Following this stream is not a job for those who forget that water always seeks its own level, that it will create its own path when necessary in order to flow, pushing aside obstacles or simply wearing some down.

Among the loopholes:

Current city law prohibits contributions from lobbyists or clients seeking a city contract or that are from a corporation. However, contributions from clients seeking land use decisions such as rezoning doesn’t fall under the prohibition. Also, corporations that establish an arms-length entity, for example PG&E’s employee committee, funded entirely by PG&E, is exempt from the prohibition.

The report points out a key missing element in ethics reporting: Nobody tracks the outcome of the decisions that big money is spent trying to influence.

Tracking spending requires the public to sort through several data files and, importantly, does not include the outcome accomplished from lobbying, behest payments, expenditure spending or permit assistance … The outcome from influence spending could be documented if there were political will because various data fields exist such as Planning Department approvals, contract applications and approvals, and other sources but Ethics and other city departments have never sought the resources to make the connections, which arguably are the most important for voters and the public.

One loophole for contractors is the “expiration of the donor prohibition 12 months after a contract is signed or closes, even after the candidate’s election is over without remaining debts,” according to the study. This means that candidates and officeholders can still accept gifts and expenses for dinners, taxis, and more more, even after the election is over.

And because the city fails to collect information from several categories, the $12 million is likely less than the actual amount promised or paid to influence city decisions. Specifically, expenses for polling related to lobbying is not usually included in reports, despite reporting being required.

Nonprofits are also exempt from laws requiring them to disclose any costs spent to influence decisions affecting them or their industry. According to the report, an estimated $1 billion is accounted for annually in city contracts with nonprofits.

Because there is no set standard for disclosure in San Francisco, extracting this data was challenging for a few reasons, according to the study.

For one, there is a lack of consistency in spending reporting rules and a lack of standardized forms. Also, the database from city officials is out of date and the office held is only accessible by senior staff.

Bush said this report demonstrates how difficult it is for average voters, as well as the public, to match the “influence of special interested with their big money.”

“The city is not doing a good enough job on transparency,” Bush said. “It’s very hard to figure out who’s giving money and for what purpose. The city has set up different categories that say, this money is spent for economic development, or this money is spent for housing, but they don’t say things like, money spent for obtaining contracts, and yet contracts are the one area where we say, eh, lobbyists, cannot spend money, so you have to take a look at the information that’s not readily available. I think one of the things that people don’t realize is the extent to which there are so many routes that money takes to reach policy makers.”

Bush argues the information from this report are a call to action, to create greater transparency and accountability that what we already have.

Citizens and residents who hope to have their voices heard are allowed up to three minutes to testify at Board of Supervisors committee hearings and can speak at full board meetings although not if the matter were heard in committee. Some departments have commissions where residents can speak under the three-minute rule.

However, such major departments as the Department of Public Works, the Mayor’s Office of Housing and others have no commissions or avenue for formal on-the-record public comment.

There is no established system for residents to meet with the mayor to express viewpoints although some past mayors set aside a morning each month for public access. This has not been done for several years.

Notwithstanding the city’s commitment to transparency and accountability, a not insignificant amount of money is spent out of sight, but which aims to influence city decisions.