48hills is soliciting Letters to the Editor from our readers for publication consideration. Share a story, thought, poem—or simply go off (creatively, please). Due to volume of submissions we regret we cannot respond to or publish all letters. Letters may be edited for length and style. Submit yours here.

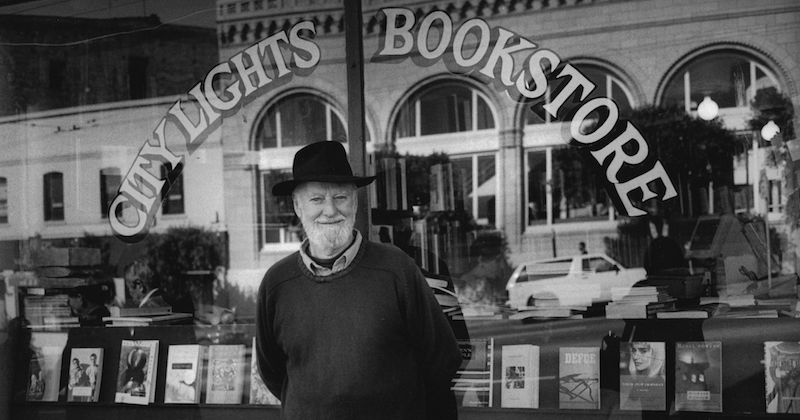

RE: “Literary Lion Ferlinghetti exits, but his community legacy roars on“

I never met Ferlinghetti in person but I met the person in Ferlinghetti. I was working as a file clerk while attending San Francisco State. There I was in the back trying to put everything in alphabetical order when a co-worker gave me a copy of A Coney Island of the Mind. I was trying to be a poet and I would turn the pages of the book which was a carousel of the imagination. I became immune to paper cuts within the confining, if not conniving, file room. In those pages was jazz and heart and pain and in the fine print he offered up a dose of instructions on how to dissect my own heart. I did and found a balloon that lifted me into ordinary language over a field of blooming Ferlinghetti flowers that were anything but ordinary. It was the language of the people, the keenness of the poet’s eye that pointed me in the direction of light. He showed that it was not obscene to be a dissent human being.

I grew up in North Beach. I saw the old Italian men that he wrote of. I was a little more than knee-high standing at the fence watching the men playing bocce ball; old men in their sweaters and hats and shoes tossing the ball through the ages, its axis rotating in a state of change and in the poet’s mind a change of state. And as in that game there are lines. Lawrence taught me that the poet cannot cross the political line. The poets are here, the politicians are there. They are not us, we are not them. He had the nerve to believe that poetry could change the world, or at least hit a nerve.

Back in 1997 my late Uncle Al Robles’ book of poems, Rappin’ with Ten Thousand Carabaos in the Dark, was published. We were gathered at City Lights for the launch. People shared stories as we waited for the reading to begin. Then something odd struck all that were present, Al wasn’t there. An hour or so passed and still no Al. Then somebody began reading from the book, then another followed by another. The poems celebrated the community, remembered the struggle for the I-Hotel and the fight for housing. We passed the poems from hand to hand in honoring, not my uncle, but the community in which he honored. Where was he? Rumor had it that he was across the street at Carl’s Jr. watching the whole thing. Uncle Al always said that we needed a place for poets to come together, to create community through poetry. City Lights gave us that place. It’s light will never go out. Thank you, Lawrence.

—Tony Robles, Peoples’ Poet

RE: “Literary Lion Ferlinghetti exits, but his community legacy roars on“

February 24, 2021: That was Etel Adnan’s 96th birthday (Happy Birthday, Etel!), the day following the news that Lawrence Ferlinghetti had passed. By chance, I had taken my copy of Oracular Transmissions on my after-lunch walk to Piedmont Avenue, where I’ve often been spotted picking up an extra coffee and vegan confection before a few minutes of reading. I tend to read on the steps of the church that’s right there, St. Leo’s, which offers two devotional benches for contemplating a statue of the Virgin Mary and some sheltered stairwells further back from the street. Oracular Transmissions is actually a collection of three collaborations between Etel Adnan and Lynn Marie Kirby, and the central piece (the one in the middle) requires the reader turn the book to its side, and flip through a series of pages saturated with blue ink. It’s the kind of book that really must be poetry, and the person reading the book is either a poet or one of those rarities: a person who enjoys reading poetry in the middle of a rather sunny day in Oakland.

I was reading, and a woman and her dog slowly approached me. From a respectful distance, she asked what I was reading. I showed her the pages, a bit speechless because I was nervous about negotiating this moment of distance with a stranger. She knew instantly and asked me, Did you hear? Larry died yesterday. Her name’s Grace, and she went on to impress upon me, You know, everyone thinks Ginsberg was so great because of Howl. But it was Larry. He’s the one who got arrested while Allen was off somewhere. My understanding was that Allen Ginsberg was in Morocco at the time, but it hardly matters—the point was who was responsible for selling the material. Shigeyoshi Murao was arrested and Ferlinghetti turned himself in. In Howl on Trial, Ferlinghetti writes,

As for myself, I thought, well, I could use some time in the clink to do some heavy reading. But for Shigeyoshi Murao who actually sold the book to the police officers, it was a heavier story. A Nisei whose family had been interned with thousands of other Japanese-Americans during the war, he led me to understand that to be arrested for anything, even if innocent, was in the Japanese community of that time, a family disgrace. To me, he was the real hero of this tale of sound and fury, signifying everything. (xiii)

What Grace wanted to really make clear to me was that Larry was a really great man. He was an essential part of hightailing it West and the mythology that has for so long made San Francisco what it has been. She told me a little story about going to Cafe Trieste, when he told her, I never want to see you here again. The writers here only talk about writing. And one night she managed to get herself locked inside City Lights, missing her bus back across the Bay to Richmond. He brought her a plate of spaghetti with some salad.

I’d say the closest I ever came to Lawrence Ferlinghetti was my sister’s graduation from San Francisco State, when he received (virtually?) an honorary degree in front of the crowds filling Oracle Park. There he was on the big screen—the Lawrence Ferlinghetti, whose poems I’d loved as an undergraduate and whose grit I’d admired even more. Today, I respect him all the more for his accomplishments as a bookseller, his part in what scholar Loren Glass describes as “the quality paperback generation,” which was a postwar democratization of the word (with some financial perks, for sure). Even so, Ferlighetti took chances on small presses and queer presses, too. Even a commercial bookshelf can become a haven: a place for folks to distribute their mags and zines when no one else would take them.

Like countless others, I’ve spent so many hours slowly guiding my fingers across the spines’ alphabetic order in the room upstairs. City Lights is where I first saw Juliana Spahr read. Kevin Killian launched the last book of his life there, Fascination, just a couple years after the launch of the New Narrative anthology, which has led to so many other new books and rendezvous at favorite cafés. This is a place that has published my friends, literary ancestors, and heroes. Lawrence Ferlinghetti helped make it happen—not just the books, but a culture of books by which a stranger could see you on a bench reading your book sideways and sense that were a little something San Francisco about you too.

—Eric Sneathen

RE: “Literary Lion Ferlinghetti exits, but his community legacy roars on“

Lawrence Ferlinghetti is dead at 101—the bard of San Francisco bohemia; the cofounder of City Lights Books (after nearly seven decades, still a great world oasis of literary freedom); the crusty defender of creativity and weirdness. I remember having lunch with Lawrence at my former watering hole, Francis Coppola’s Café Zoetrope in North Beach, where the old poet and bookseller was also a frequent diner. I was interviewing him for my book about San Francisco’s raucous history, Season of the Witch. At one point, Lawrence turned around the interview on me and began asking questions. Why the title, he asked me? I think Lawrence was more a fan of jazz than rock. I began quoting lines from Donovan’s strangely dark hit song from 1966. When he heard Donovan’s dystopic line, “Beatniks out to make it rich,” Ferlinghetti exploded.

“We were NEVER out to make it rich!” Ferlinghetti nearly yelled at me, as we sat in a corner booth at the café sipping a Coppola red. “The Beats were always broke. Ginsberg only got some money near the end of his life when he sold all of his stuff to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas.” I explained that Donovan was being ironic, that he was warning about a world turned upside down with greed. But Ferlinghetti was still in a foul mood as lunch ended.

That’s one of the things I loved about Ferlinghetti—his toughness. That’s why San Francisco radicals like him went the distance, turning their cultural creations into beloved institutions. City Light Books has become so revered that its current operators, set up for continued success when Ferlinghetti wisely bought the landmark building, were able to raise nearly a half-million dollars from loyal customers during the COVID lockdown.

It took someone as ornery as Ferlinghetti, who was already the grownup during the Beat years, to fight for “Howl,” Ginsberg’s anthemic poem, when the poet took flight, leaving his publisher to stand trial on obscenity charges. When Ferlinghetti prevailed in the 1957 trial, it was a blow for the cultural revolution that was beginning to take shape in San Francisco.

But even as that revolution rose into a wave at the Human Be-In, where the Beats handed the baton to a new generation of seekers, massed in Golden Gate Park on a sunny winter afternoon in January 1967, the counter-culture elders still had a healthy skepticism about the oceanic upheaval they had helped create. Looking over the teeming humanity from the stage where the Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead, Timothy Leary, and they had held forth, Ginsberg turned to his old friend Ferlinghetti and asked, “What if we’re wrong?”

Ferlinghetti and Ginsberg were not wrong about the hippie invasion of San Francisco in the 1960s, which led to the gay revolution of the 1970s and the creation of the “San Francisco values” embraced by progressives around the world —and reviled by Fox News and its right-wing legions.

And Ferlinghetti was not wrong decades later when he turned against another invasion of our city, this time by the robotic hordes of the tech industry, whom he castigated as a “soulless group of people”—a “new breed” of men and women too busy with their digital gadgetry to “be here” in the moment.

Yes, Lawrence Ferlinghetti could be as crusty as day-old San Francisco sourdough. But his cantankerousness was always in defense of the right principles and people—the exploited, the underdogs, the freaks who make all the beauty in the world. Until the very end, he stayed in North Beach, he painted and he wrote poems, and he sipped wine and ate pasta at neighborhood cafes.

I want to be Lawrence Ferlinghetti when I grow up.

—David Talbot