In a stunning victory for progressives, the Board of Supes voted 8-3 Tuesday to block a massive market-rate development that would have threatened one of the last affordable areas in Soma.

The vote to overturn the 469 Stevenson EIR doesn’t kill the project, but it’s a major setback and could help advocates who want to use the site for affordable housing.

While the board has the legal authority to overturn planning decisions, it rarely happens: “I can’t remember the last time this happened on a project of this type and magnitude from a developer like this,” John Elberling, executive director of TODCO, which filed the appeal, told me.

Although technically the vote was just on the adequacy of the environmental review, the discussion at the board focused on the role market-rate housing plays in gentrification and displacement.

The vote also showed a new political shift on the board, with Sup. Matt Haney, who represents Soma, joining his more conservative colleagues, Ahsha Safai and Catherine Stefani, in voting to support the project.

The proposal for 469 Stevenson calls for 495 new apartments on the edge of the Sixth Street Corridor, home to low-income residents and SRO hotels.

As we reported last week:

And the gentrification threat for Sixth Street is already very real. The 5M project on Fifth Street will be completed this year, including its new market-rate housing. If another big market-rate project is approved on this same block as proposed by 469 Stevenson, that would put all other existing housing nearby at risk of being purchased by “investors” to be ‘flipped’ into up-market tech-worker housing.

For example, the predominantly Filipino-American 200+ unit Mint Mall apartment building, between 5M and 469 Stevenson, would immediately become a prime target for such a “reno-viction” project that could displace all of its existing tenants—legally.

A wide range of Soma groups opposed the project and asked the board to reject it. Most of the supporters who spoke at the hearing were either part of the Yimby world or from the building trades.

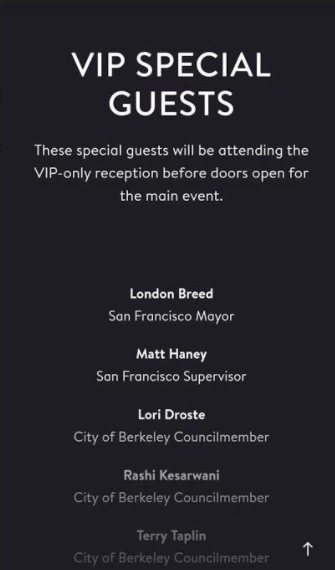

The politics of this are fascinating: Haney, who has long been part of the progressive majority on the board, is now running for state Assembly with the strong support of the building trades (and it appears, at least some of the Yimbys—he is featured, along with the mayor, at a VIP reception for a Yimby fundraiser).

Among other things, the City Planning Department relied in its approval on a study that argues there is no connection at all between high-end housing and displacement in low-income neighborhoods.

The study, which you can download here (it’s at the end of the comments and responses document), by ALH Economics, a Berkeley consulting firm, lists numerous academic studies that all take the same position‑but completely ignores equally respected studies from eminent academics that argue the opposite.

There is this, and this, and this. Top-level researchers from MIT, UCLA, and the University of Wisconsin have all argued in the past two years that putting large luxury housing developments in vulnerable neighborhoods at best does nothing to bring housing costs down, and at worst leads to widespread evictions and displacement.

“I am baffled that in 2021, the city still asserts that there is no evidence to support the argument that market-rate housing creates gentrification and displacement,” Sup. Dean Preston said at the hearing. “The City Planning Department needs independent guidance before it continues to repeat these assertions, which frankly are not only inaccurate but provided by a consultant who works for developers.”

Sup Connie Chan added:

Where 469 Stevenson located is considered as a sensitive community where that is really at risk of gentrification and displacement, so I think my question or, really more as a comment, that it’s interesting that planning did not broaden its analysis and really take a look at independent and academic studies and instead rely upon a developer analysis on gentrification impact where we know that this is really market-rate housing for profit.

Jessica Range, a principal environmental planner, told Preston that the California Environmental Quality Act doesn’t specifically address gentrification, unless there’s a physical impact on the environment. “This was a site-specific analysis,” she said.

But as Preston noted, gentrification changes the entire sense, physical and socio-economic, of a community. Among other things, market-rate housing likely means more car traffic (if nothing else, from Uber and Lyft, Amazon, and food-delivery services).

The Planning Department, as it has in the past, basically ignores that.

There’s more:

At one point, under questioning, an executive from the developer, Build Inc., acknowledged that there is currently no financing for the project and the company doesn’t even own the land. Founding Partner Lou Vasquez said that he couldn’t predict how much the new units would rent for because “we don’t own the site or have financing in place to build it.

The supes didn’t even know how to respond. “I think that silence is from shock,” Sup. Shamann Walton noted.

One of the central issues in the debate was the EIR’s analysis of seismic safety at the site. The report never really addressed the issue, which is pretty critical since the land under the proposed building is swampy and unpredictable.

Another was the impact on local historical resources; the EIR pretty much dismissed those are irrelevant.

Haney asked the planners whether the lack of discussion of the seismic in the EIR was even relevant, since the building can’t get a final sign-off until city officials review the plans and make sure they are up to code. (On the other hand, the Millenium Tower was built to existing code.)

Sup. Myrna Melgar asked planners whether they had anyone on staff who could determine the geological stability of the site.

No.

Does the Department of Building Inspection have anyone who can do that?

No.

So the city would rely on the developer’s experts. This has not always worked well in the past.

Sup. Aaron Peskin noted that the EIR utterly failed to deal with the potential impacts to historic buildings adjacent to the project.

In the end, eight supes spoke against the deal. They raised a wide range of questions. Then Haney made a motion to scrap the appeal and approve the project.

He made the classic Yimby argument—that the city needs more housing, including larger family-sized units, and that this project includes sufficient affordable housing. He said that the residential hotels in the Sixth Street area were already protected by the city.

That motion failed, 3-8, with only Stefani and Safai supporting him. Then a motion by Peskin to uphold the appeal passed by the same margin, with the same votes.

J.K. Dineen notes in the Chronicle that Mayor London Breed was furious about the vote:

Mayor London Breed, who supported the development, blasted the vote, suggesting that the opposition was based on “vague concerns.” She called the decision a “perfect example” of “how San Francisco got into the housing crisis.”

“This project met all the criteria for approval and it would have created 500 new homes on what is currently a parking lot surrounded by tall buildings, located near transit,” she said. “We can’t keep rejecting new housing and then wondering why rents keep rising.”

Dineen also implied that the decision was all political, based on seven supes who support David Campos for Assembly going after Haney. (Actually, only six: Melgar, who opposed the project, hasn’t endorsed anyone in this race.)

But Walton, who supports Haney, voted against the project—because, as I have always found with Walton, he puts principles ahead of politics. This was, he agreed, a bad EIR and a bad deal.

On Twitter, Haney has been again repeating the Yimby line and stirring up anger at his progressive colleagues. (If he’s concerned about the impact of building more office space, why doesn’t the city stop approving more office space?)

But again: This is about facts on the ground, reality—and the reality is that numerous studies (and the lived experience of thousands of current and former San Francisco residents) shows that market-rate housing doesn’t solve the city’s crisis, and typically makes things worse.

A majority of the supes get that. The mayor and the Planning Department do not.

Elberling noted that

The SOMA community’s hope is that this crucial site, now a parking lot, can be acquired for future

affordable housing development. That is what Sixth Street, our communities, and our city need the

most, and this is a perfect location to do it.

The developer may try again—but there’s a lesson from the Mission here. If the city makes it hard to build bad projects, there’s a much better change of getting a good project.