Fifty years ago, February 7 saw the simultaneous release of two major-studio films destined for long-range status in the pop culture cosmos—though I doubt anyone expected that at the time. One was an immediate flop, the other a big sleeper hit from which little success had been anticipated. The latter was Blazing Saddles, which made Mel Brooks for a time the medium’s leading comedic filmmaker. But before that, he’d been a TV writer whose movies (including The Producers) had been commercial fizzles. Saddles had no box-office stars (Richard Pryor’s drug issues made him uninsurable, so the role Brooks had written for him went to Cleavon Little), and its parodic genre target—westerns—was as dead in 1974 as it would ever be. Nonetheless, the movie became huge, lending its writer-director a career propulsion that lasted nearly a decade, though he’d never strike such a loud popular chord again.

I actually much prefer Young Frankenstein, which came out at year’s end, was nearly as successful, and remains Brooks’ best film by general consensus. Saddles is both anarchic and strictly Borscht Belt; it has some great ideas (and Madeleine Kahn sending up Dietrich), but ultimately it’s too scattershot, as well as too well-defined overall by having one entire scene that’s a fart joke. I was yanked from the theater at a tender age by the prudish sister I’d conned into taking me. But it wasn’t that much of a sacrifice—it wasn’t that funny—and she was right, it was vulgar, in a dumb way. Catching up to the whole thing at some later point, it still seemed a little mystifying as a massive hit. But perhaps at the peak of the Watergate era, with the Vietnam War still lumbering on, America just really needed some fart jokes.

The other release celebrating its 50th this week is one almost no one liked then, though since it’s become a cult classic. Zardoz is an apex of that era of thinky, often dystopian-future sci-fi that flourished (if that’s the right word) between 2001 and Star Wars. Before Kubrick, the screen genre was mostly about monsters; after George Lucas (allowing for the fact that his 1971 THX-1138 was thinky SF par excellence), it was mostly about space battles… and monsters. But for a while there, it was about ideas, and ecology, and psychedelia, and other hot topics of the era.

Zardoz starts with a floating head talking to us in empty space, not unlike the disembodied lips that would open Rocky Horror a couple years before. This bit, featuring Niall Buggy as a de facto Wizard of Oz (i.e. the man behind the curtain of a fake deity), was inserted late when studio executives begged John Boorman to provide audiences some kind of introduction that might help make sense of the ensuing 100 minutes. He complied; but it didn’t help. The director later admitted he was doing a lot of drugs during both screenwriting and production, a fact unlikely to surprise anyone who’s ever seen the film.

It was a fantasy original thought up when Boorman accepted that his dream of adapting The Lord of the Rings was too costly for financiers of the era. Nonetheless, he was just coming off the critical and commercial triumph of Deliverance, so funding was secured for this much smaller-scaled concept, even if the script triggered “what the hell?!” responses from executives. For tax purposes, Zardoz was shot in the Republic of Ireland, which was politically problematic (“the Troubles” were at a violent peak) but also such a bonanza in visual terms that he would shoot there again (notably Excalibur), and become a permanent resident. Apparently the frisky shenanigans were such around this film’s production that the following year, the local birth rate jumped 15%.

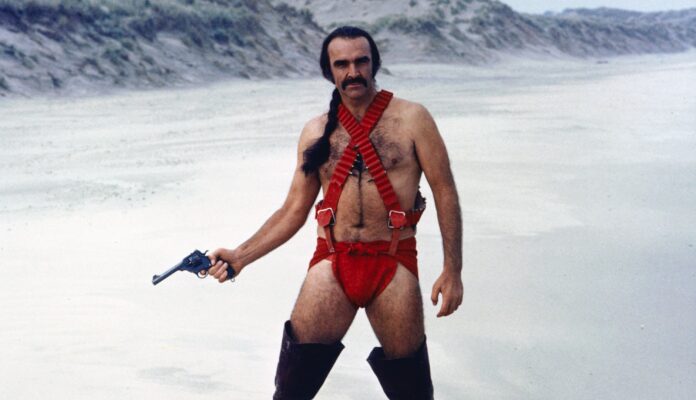

Well, presumably having Sean Connery run around in a red diaper-slash-thong was inspirational to all, though one suspects he felt otherwise about it. (This is the rare movie in which that actor’s usual authority seems on shaky ground, and no wonder.) He’d been persuaded to don the loincloth for a much lower salary than usual because he was then still struggling to establish a post-007 screen identity. He plays Zed, a warrior of “the Brutals” in 2293. They are marauding barbarians given carte blanche to rape, pillage and murder peasants of “the Outlands” by a floating giant stone “god” known as Zardoz (its instructions voiced by Buggy). It’s a grim sort of existence, human civilization reverting to the Dark Ages in the wake of some environmental catastrophe.

But one day Zed stows away on this flying god-ship, waking up to discover its “home” is a comparatively paradisiacal sealed community called “the Vortex.” There, “Eternals” live lives of effete luxury not unlike the future society in Woody Allen’s Sleeper, released a couple months earlier. These gauzy hippie-socialite types likewise have terrible wigs, inflatable sculptures, and other signs of having evolved too far. They’re so refined, they indict each other for “psychic violence,” waving accusatory jazz-hands that bestow the ultimate punishment of aging.

This shallow utopia needs our hairy hero’s dose of he-manliness—these skinny topless women and emasculated men have forgotten how to live, and worse (being immortal), how to die. It is up to Zed to “liberate” them by means of death and destruction, bringing “an end to eternity.” He will need to repopulate the planet the old-fashioned way, in partnership with Consuella (Charlotte Rampling), a particularly haughty Eternal who swoons into his arms the second she stops calling for him to be killed. Their nonexistent chemistry, and her performance here, is such that you will understand why it came as a surprise some years later when people realized Rampling could act.

Of course, any acting would be an uphill effort in Zardoz, given the script full of windy riddles and philosophical noodling, as well as a fair amount of entirely un-erotic nudity. This muddled mix of satire in the realm of The Ruling Class, psychedelic hippie mysticism a la Castaneda, and fantasy somewhere between Tolkien and Silent Running is frequently just plain nuts. But it’s fluidly nuts—it all works on its own terms, never seeming inept or dull. Boorman’s visual imagination is singular no matter how silly the film gets, painting a world remarkably distinct given his relatively low $1.5 million budget. (Two years later Logan’s Run, a more commercially successful false-future-utopia movie, would cost about five times as much.) Slow-mo, reverse motion, projected images, and much more are piled on to trippy results that must have delighted heads from the get-go.

Though few of them would have seen Zardoz until it began getting revived on campuses and in rep houses, since the film was initially greeted as a bizarre and confusing boondoggle. (Point taken.) Its theatrical run was fleeting. Connery soon course-corrected his career with a run of respectable period pieces, cozy all-star mystery Murder on the Orient Express followed by colonial high adventures The Wind and the Lion and The Man Who Would Be King. There would be no more diaper-thongs in his future. Boorman next applied himself to an even more notorious flop, 1977’s Exorcist II: The Heretic, before his luck took a sharp turn upward. But Heretic, too, is a deliciously crazy enterprise whom many people love. It is a folly—like Zardoz, a great folly, one that would be remembered and rewatched for its lovable eccentricities long after top hits of their year (The Towering Inferno, anyone? The Trial of Billy Jack?) had begun rusting in the celluloid junkyard.

Visions of the future aren’t lacking among new releases, though these days you’re highly unlikely to find as wild an imaginative leap as Zardoz, which is available from most streaming platforms. Going in quite the opposite direction, at least stylistically, is UK television director Mahalia Belo’s first theatrical feature The End We Start From, adapted from Megan Hunter’s 2017 novel. Jodie Comer of Killing Eve plays a 30-ish Londoner who is heavily pregnant when torrential rains cause flooding—not just impacting a few areas, but the entire country. (We’re not privy to intel re: whether the same crisis is happening around the world.) Infrastructure collapses, food and housing become desperately scarce; society quickly degenerates into violent chaos.

Now with a newborn, our heroine (none of the characters here get names) first finds shelter with her in-laws (Mark Strong, Nina Sosanya), then elsewhere. But the general desperation means no place is truly safe, so she ultimately hits the road with another new mother (Katherine Waterston), en route meeting additional figures played by Gina McKee, Benedict Cumberbatch, and others. What motivates Comer’s protagonist as much as protecting her baby is the aching need to find the husband (Joel Fry) she’s been separated from. It is a tribute to the actress and to the film’s sensitivity that this longing never feels like a stock, sentimental narrative device—it is the story’s soulful center.

Though often fraught with danger, The End… doesn’t have the nightmarish horror-adjacent quality of many similar environmental-apocalyptic tales: One unremarked but notable difference is that, this being the UK rather than the US, almost no one has a gun to run amuck with. Its survivalist saga stays on an intimate plane. Destruction spectacle is scarce, yet the cumulative emotional impact is considerable, making this an unusually touching piece of near-future fiction. Following a brief run in theaters, it hits On Demand platforms this Tues/6.

A more conventionally action-packed, technology-forward form of sci-fi is offered by Czech director Robert Hloz’s Restore Point, a coproduction between several Eastern European nations. In 2041, Em (Andrea Mohylova) is a “lone wolf” police detective investigating a series of murders. Escalating socioeconomic inequality has spiked violent crime, which actually is no longer such a terrible thing, because all citizens have the right (and the means) to be “restored” to life after a premature death. But the elements required to “reboot” must be backed up every 48 hours, and these killings have deliberately targeted those who’ve neglected or were prevented from taking that precaution.

There’s a Blade Runner-ish feel to this thriller, not so much in its less-distinctive aesthetic but in its vaguely noir-ish mystery plot, which similarly toys with advocates and opponents to science redefining humanity’s limits. While there isn’t a lot of action here, Point is nonetheless slick and ambitious. If I didn’t find the convoluted story or familiar character types as involving as intended, those looking for sci-fi cinema outside the usual Hollywood parameters will definitely want to give it a look. XYZ Films releases it to U.S. On Demand platforms this Thurs/8.