By Caitlin Donohue

Earlier this month, the cover of San Francisco’s oldest bilingual newspaper, El Tecolote, was given over to a review of the new documentary on the life of Chicano journalist Rubén Salazar. The Juárez-born, El Paso-raised writer and Spanish-language TV news director was slain by an LAPD sheriff’s deputy while he was drinking a beer in a bar. The killing took place after Salazar attended an anti-Vietnam War protest in 1970, and was seen by many as the cops’ revenge for the journalist’s unflinching coverage of police brutality towards the Chicano community. It was eventually ruled an unfortunate accident.

El Tecolote screened the documentary, Phillip Rodriguez’s Man in the Middle, as a fundraiser for the paper last weekend at the Roxie Theater in advance of its national premiere on PBS tonight.

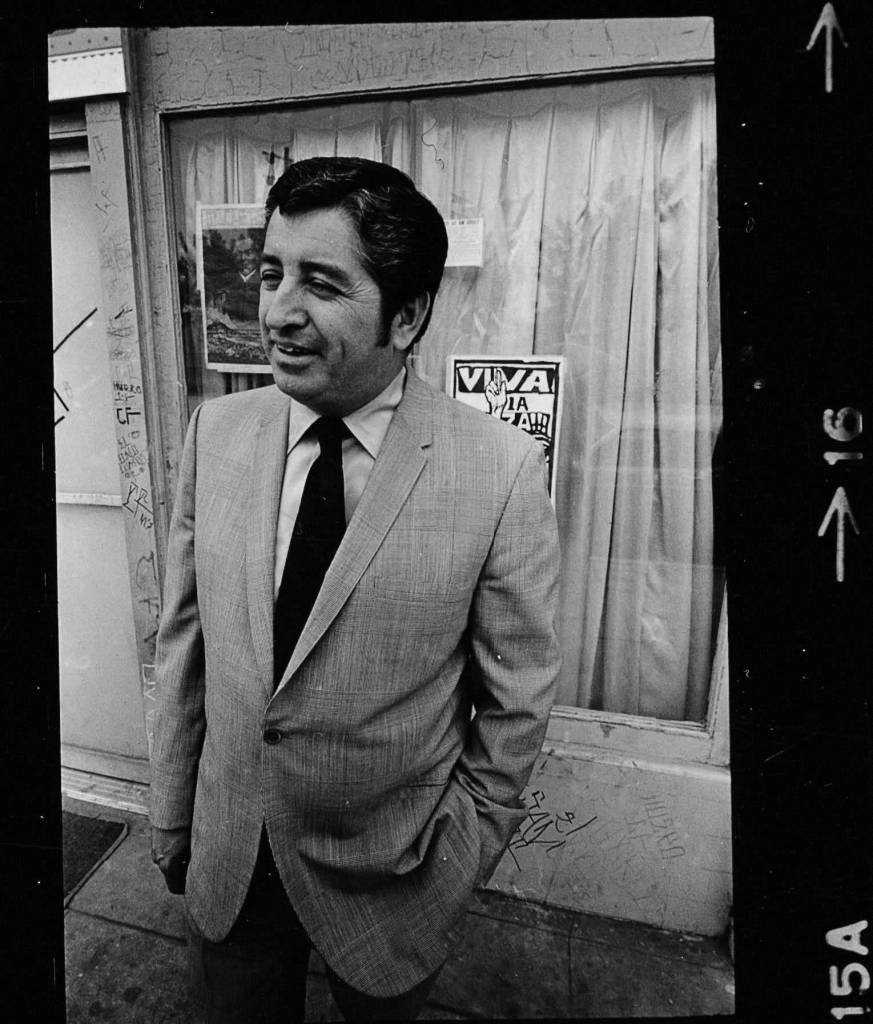

Here’s what you need to know about Rubén Salazar, a contemporary of Cesar Chávez and Corky Gonzalez who provided a voice in mainstream media to the Chicano Power movement of the 1960s. Before he was snapped up by the LA Times, as the paper’s first Hispanic staff writer, he worked as a reporter in the Bay Area – first covering small town politics in Petaluma and then San Francisco. At the LA Times, he was assigned to cover the Vietnam War, then named bureau chief of the paper’s Mexico City newsdesk.

According to the film, he was devastated both professionally and personally when the Times called him back to SoCal to document the accelerating unrest in LA’s Chicano community. But it was there that Salazar, once content to blend in as best he could to the all-male, all-white newsrooms of the that era, was radicalized. He was careful not to become a mouthpiece for the charismatic activists of the time, but wrongful police killings and despicable treatment of Chicano life by law enforcement began to fill his LA Times column, and were regularly covered by KMEX, the Spanish language TV station that out-bid the Times to secure him as its news director.

By the time of the Chicano Moratorium, planned to be one of the era’s largest peaceful demonstrations LA had ever seen, Salazar was telling friends that he was receiving ugly threats from the police that he’d gone too far. When the day’s anti-Vietnam protest turned ugly and police began beating participants, Salazar and his KMEX co-worker Guillermo Restrepo decided to wait out the turmoil in the nearby Silver Dollar Bar. Police would later say they’d received reports that a man with a gun had entered the club. In a confusing order of operations, they forbade anyone from leaving the Silver Dollar, then ordered them out, then fired tear gas canisters into the establishment. One canister blew a hole through Salazar’s head.

Given its subject matter, it was easy to expect a JFK-style conspiracy film from Man in the Middle. But true to its name, and the rational journalist it profiles, the story is grounded much more in fact than theory. You do get computer renderings of the Silver Dollar’s layout (including the delightfully balloon-chested illustrations of women that comprise its décor). But the film is surprisingly gentle with Salazar’s killer, Deputy Thomas Wilson, who comes across as a doltish public servant in the interviews filmmakers somehow secured with him. (Although an audible shiver rippled across the Roxie audience when Wilson admitted he almost loaded the same tear gas gun to shoot an irate audience member while the deputy was testifying as to how the weapon worked. “It looked just like the barrel of a 45,” Wilson remembers of the rolled-up piece of paper the irate protestor brandished in his direction.)

If new generations learn about Salazar’s extraordinary life through Man in the Middle, the film should be counted a success. But Rodriguez and his team also wanted to cast doubt upon whether the case is truly closed. They struggled to win access to the eight boxes of evidence the LAPD has been holding in relation to Salazar’s death. “That was the most difficult part of making the movie,” said Ricardo Lopez, the film’s advisor and associate producer, at the panel discussion that followed the screening at the Roxie. He shared the stage with activists involved in the planning of Chicano Moratorium. “But getting the files, to me, solidified the validity of this documentary,” he said.

As we entered the Saturday night screening, each attendee was handed a copy of that week’s El Tecolote. The issue adorned with a photo of Salazar in Mexico City in his trademark dapper suit was no longer the most current edition. This week’s cover model was a protester eating a burrito at the first meeting of Burritos en Bernal, regular demonstrations being staged on Bernal Hill in remembrance of Alejandro Nieto. Nieto was shot over 10 times by San Francisco police officers that mistook the off-duty security guard’s taser for a lethal weapon. Clearly, the civil rights battle in which Salazar and his generation fought has yet to be won.

Was it depressing, I later asked El Tecolote’s founding editor, Juan Gonzales, to screen this film when police carelessness (to put it mildly) in regards to Latino life is still such a concern over 40 years later? “It’s all part of a process,” he said. “[Salazar’s generation] started a strong movement. They left a legacy so that others can follow in their footsteps. Long ago, we said the movement is dead. That’s not true. Maybe it’s not as visible, but it’s there. Just because you don’t hear about the work being done doesn’t mean it’s not happening.”

“The community is always plagued with police brutality, police overreacting,” the founding editor continued. Gonzales was enthused, however, by the number of young people in the nearly sold-out theater for the Man in the Middle screening, students from CCSF and other schools around the Bay. “Work still needs to be done to carry on the torch, to make things right.”

Rubén Salazar: Man in the Middle, Airs on PBS Tue/29 9pm; Wed/30 3am.

DVD available for purchase at www.pbs.org