SCREEN GRABS The National Endowment for the Arts and PBS seem headed for budgetary doom under President Trump, although not because they’re costly and expendable—together they comprise a mere drop in the bucket of the annual Federal budget. Instead, the real reason is that these oft-threatened institutions reflect the fact that non-commercial creative artists are often a critical thorn (however small) in the side of conservatives, and this is a regime unusually blatant in its belief that news media, entertainment, and art should tow its own official political line. This is a POTUS who often seems barely aware of pressing national and international issues, yet is acutely attuned to how Saturday Night Live just satirized him.

Such conflicts were rarer in the “classic” era of Hollywood entertainment, which for our purposes here we’ll define as anytime before censorship laws began to collapse amidst wider societal changes in the mid/late 1960s. With no ratings system in place on the big screen (let alone the small one) during that period, movies had to possess a certain “one size fits all” inoffensiveness that wouldn’t traumatize children or alarm moralists. Hence not only nudity, cursing and other breaches of standard decorum were generally off-limits, but also overt political commentary that might alienate large sections of the mass audience.

However, this last stricture was one occasionally if cautiously trespassed over the decades by filmmakers eager to have their work sport some actual social relevance. This Wednesday, the Roxie and Midcentury Productions present “AGITPROP! An Evening of Mid-Century Social Justice,” a three-part evening that showcases the Hollywood of 55 to 70 years ago as it explored social justice issues. The program encompasses one famous film noir, one long-forgotten “B” flick, and one once-hotly-controversial episode from a vintage TV series.

For all the sacrifice it demanded, World War II also widened the horizons of many Americans, making them feel more a part of hitherto unfamiliar cultures both at home and abroad. Just as the horrors witnessed in that conflict surely influenced the rise of the post-war noir genre, with its violence and cynicism, a parallel new awareness of tolerance and injustice found expression in several films of the era touching on hitherto unmentionable social issues. Racism was one obvious subject overdue for screen portrayal, with the status of African-Americans before the Civil Rights Movement depicted in acclaimed features like Intruder in the Dust and Pinky (both from 1949).

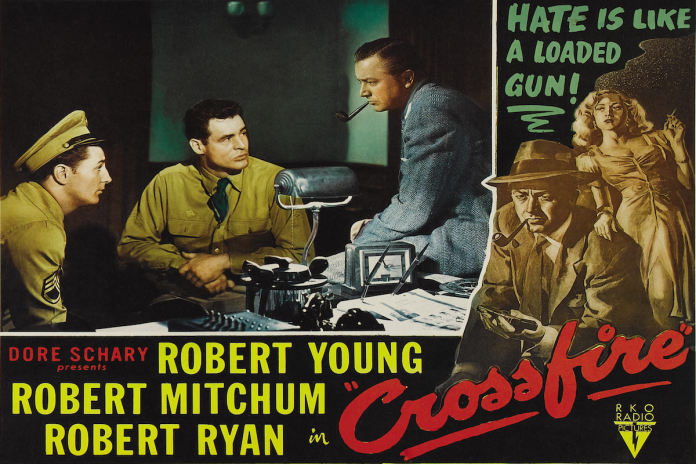

Despite the prominence of Jewish executives and talent in the industry, anti-Semitism was rarely acknowledged onscreen until two high-profile 1947 releases. One, Elia Kazan’s Gentleman’s Agreement, got eight Oscar nominations and won three (including Best Picture); the other got six nominations, winning none. Yet today the first film looks like earnestly dated do-good-erism, while Edward Dmytryk’s Crossfire still crackles with atmosphere and tension, thanks largely to its couching the “message” in a noirish crime thriller. Its almost Rashomon-like plot has to do with the investigation of a police detective (Robert Young) into the murder of one decommissioned soldier (Sam Levene) last seen in the company of several others. All parties offer their differing recollections (and/or lies) on what really happened.

The strikingly directed and shot (by J. Roy Hunt) RKO feature provided a big leg-up to several rising young actors, including Robert Mitchum, Gloria Grahame and Robert Ryan—the latter so memorably loathsome in his role that he eventually blamed it for years of villainous typecasting. But despite its eventual great success, the movie’s subject matter was considered so “risky” that the studio had to be arm-twisted into making it, agreeing only on condition of a notably tight budget and shooting schedule. The original trailer consists entirely of RKO congratulating itself for being so “daring”:

Ironically, even the central theme was a compromise: in John Paxton’s source novel, the victim wasn’t Jewish but gay, his murder an expression of virulent homophobia rather than racial prejudice. (Hollywood wouldn’t be ready to go there for another two decades or more.) An equally bitter truth was exposed by what happened off-screen to some of the film’s chief architects. That same year, Dmytryk and producer Adrian Scott—both of whom had briefly been members of the U.S. Communist Party—were among the “Hollywood Ten” who refused to testify before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. They were each jailed and blacklisted from industry work for that stance, with only Dmytryk ever making a full “comeback.” Their fates were already sealed by the time Crossfire was up for its Oscars, which no doubt factored in its failure to bring home any statuettes.

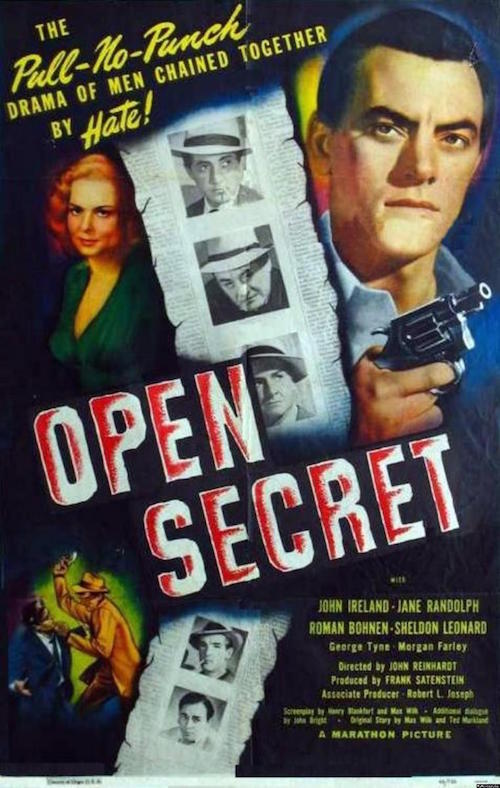

The other feature the Roxie is showing may well have been inspired by Crossfire’s success, though it hardly shared in that film’s popularity or acclaim. Produced by one tiny company—Marathon Pictures, short-lived despite its name—and released by another (Eagle-Lion), the modest Open Secret stirred scant notice when it played the bottom half of double- and triple-bills in 1948.

On their honeymoon, Paul and Nancy Lester (John Ireland, Jane Randolph) visit his old army buddy, who lets them stay in his apartment at a boarding house in a working-class city district. Yet before they actually get a chance to see him, they discover that he’s been murdered. Sticking around to help the investigating police dick (Sheldon Leonard, later a well-known TV producer and director (on The Dick Van Dyke Show, etc.) however they can, the couple gradually realize this neighborhood is a hotbed of racism and general scumminess. Here, hate crimes are directed at anyone deemed not “the right kind of people”—notably “kikes and wops,” aka Jews and Italians.

When his bride wonders aloud at such ugly behavior, her husband muses “I suppose some people can’t live without hating—it’s the only way they can feel superior.” Directed by John Reinhardt, a native Austrian whose transient career had briefly landed him in Hollywood at this point, Open Secret is a pedestrian “programmer” at first glance that gets better and better as it goes on, eventually growing quite exciting and powerful.

The third element in the Roxie’s evening (although the first shown, at 6pm) is an episode from a once-prominent but now little-remembered TV series, The Defenders. Launched in the fall of 1961, it starred E.G. Marshall and Robert Reed (yes, the future Mr. Brady) as father-and-son attorneys whose shared practice confronts them with a wide range of social and ethical issues. Though tackling “controversial” themes would soon become fairly standard amongst the more ambitious broadcast dramas, The Defenders was virtually alone in doing so at its outset.

The first-season segment being shown here is “The Benefactor,” in which the lawyers find themselves defending a respected veteran doctor (Robert Simon) who has performed illegal abortions—and in doing so, making the larger case that abortion shouldn’t be illegal at all. This was shocking terrain for viewers at the time. Indeed, CBS found that none of the show’s usual commercial sponsors were willing to run ads during this particular episode. Yet that helped generate national publicity, with the result that ratings were particularly high. Somewhat surprisingly, there was no angry backlash afterward; in fact, most viewers who bothered to write the network were highly supportive. The positive reception seemingly encouraged the fledgling show to continue emboldening its approach towards hard-hitting subject matter.

While talky and earnest in the classic manner of yesteryear’s TV courtroom dramas, “The Benefactor” (which was written by Peter Stone and directed by Reginald Rose), remains a potent piece of agitprop—forcefully making the point that restrictive laws at the time often forbade legal abortions even in the case of rape. They also drove many women to back-alley procedures from which they risked mutilation or even death.

Eleven years later, “Roe v. Wade” finally made abortion a legal option for all. Will 2017 be the year that is it overturned? Stay tuned.

“AGITPROP! An Evening of Mid-Century Social Justice’ plays Wed/26 at Roxie Theater (The Defenders 6 pm, Open Secret 7:30, Crossfire 9:15), SF, $15. Tickets and more info here.