ART LOOKS Traversing decades, mediums, and populations, Queer California: Untold Stories, on view through August 11 at the Oakland Museum of California (OMCA), aims to shine a light upon the queer individuals, places, and objects from across the Golden State that have remained marginalized or overlooked, even within mainstream accounts of the LGBTQ past.

At the same time, the exhibition aims to acknowledge the limits of what it can achieve as a corrective to the historical record. “Sometimes things are left out of mainstream narratives for banal reasons, sometimes for political ones. Sometimes these overlap. Some stories we do not know, and many cannot be recovered,” reads one wall text toward the exhibition’s start. As Queer California goes on to show, this admission doesn’t mitigate the stakes of attempting such a recovery. If anything, it can reveal new ones.

To this end, curator Christina Linden has wisely taken this disavowal of mastery as an opportunity to enlist a who’s who of contemporary queer artists—many with ties to the Bay Area—to act as docents and commentators on the archival material on view.

Case in point is the exhibition’s opening installation. Gilbert Baker’s hand-sewn prototype for the rainbow pride flag reveals that his original design had eight symbolic colors. Baker had to jettison two of them—turquoise and hot pink, meant to signify sex and magic—because they would make the flags too expensive to mass-produce. The artist Amanda Curreri makes these colors central to her more abstract 2013 flag, titled Misfits 1979 (Sex and Magic), which hangs behind Baker’s. The pairing encapsulates the tension between elision and rediscovery that animates the best work in Queer California.

Chris Vargas’s large-scale installation, MOTHA (The Museum of Transgender Herstory and Art), for example, turns a meta-critical lens on this dynamic, creating a miniaturized version of Queer California in the process. MOTHA is an ongoing conceptual project through which Vargas works with existing archives and museums to source and display materials related broadly to trans history.

The resulting “exhibitions” critically examine how institutional forces, along with scholarly research and community-lead activism, shape that history, while still allowing previously hidden or overlooked items to go on view. Here, behind a proscenium that resembles the kind of neoclassical façade one typically associates with The Met or The British Museum, Vargas has assembled objects and art by and about a pantheon of Bay Area transgender pioneers: there’s one of Sylvester’s sequined jackets; an incredible checkers set by painter and trash drag superstar Jerome Caja; and memorabilia from Jose Sarria’s days performing at the Black Cat.

For all of the larger installations, such as Vargas’s or Kaucyila Brooke’s intricate forensic mapping of former gay and lesbian bars around Los Angeles, some of Queer California’s more fascinating contents can be found in the vitrines and nooks at the edges of the gallery’s open floor plan. I had no idea, for instance, that the Los Angeles chapter of the Gay Liberation Front had attempted to create a rural gay utopia in Alpine County in 1970. Even more surprising is the Berkeley Barb clipping detailing how one member of the group dissented on the grounds that to establish such a community would infringe on native sovereignty, echoing current debates on the intersection between settler colonialism and queerness.

If Queer California can be faulted it is not so much for what may have been left out, but for its good-faith effort to include so much. The installation is, in a word, dense.

The timeline on the main gallery’s rear wall, to pick one notable example, is packed with fascinating anecdotes and ephemera but the format feels at odds with the resolutely non-linear presentation strategies that precede it. The attempt to use every inch of available wall space also leaves some of the visual art pieces feeling orphaned or shoehorned by dint of their proximity to more fully integrated groupings. Andrea Bowers delicate pencil portrait of a trans May Day protestor is drowned out by Resilience of the 20% (2016), the imposing 1,300-pound bronze cast of the hunk of clay artist Cassils sculpted with their bare fists during their durational performance series, Becoming an Image.

It’s also easy to miss things. I only realized I hadn’t seen H. Lenn Keller’s 1980s photographs of Bay Area black lesbians, for instance, until I reviewed the exhibition checklist. Whether by design or accident, return visits to Queer California are a necessity.

This packed cocktail party approach to curating and installing is not without its local precedents. In many ways, Queer California feels like our moment’s analog to In A Different Light, the groundbreaking 1995 survey of queer art organized by Larry Rinder and Nayland Blake at the Berkeley Art Museum. Just as that exhibition proposed alternate art historical genealogies between then-emerging Bay Area artists such as D-L Alvarez and Vincent Fecteau and canonical antecedents like Romaine Brooks or Andy Warhol in salon-style hangings, so too does Queer California suggest that queer visual artists – as opposed to the institutions that frame them — may be the canniest interpreters of a history that is both shared and disparate.

Despite its clear love of the archive, Queer California seeks to make clear that unearthing LGBT history is a way back to a queer future. “The future is queer, because the present is not enough,” declares wall text at the start of the exhibition. Queers look to their past to dream and propose what lies ahead, what could be.

Alvarez, who shows up in Queer California, too—his graphite, ink and collage pieces bookending the exhibition—provides another gloss on this sentiment. “Timelines are circular and mixed through with fact and fiction,” reads a quote attributed to the artist, also located at the exhibition’s outset. It’s an appropriate appraisal of Alvarez’s own work, which weaves thin stripes of cut paper into abstract tapestries of color and text—the tickertape of history shredded into a confetti cloud—but it also points to the malleability of history as material when places in queer hands.

Engaging with the past becomes a means by which queers continue to question and establish their identities, creating new lineages and new forms of community in the process. If, as the old Marxist saw goes, history is what hurts, Queer California demonstrates, with an overfull heart, that the past can also give us life.

ALSO ON VIEW:

It’s not even Pride month yet and San Francisco is already chockablock with visual art exhibitions that cruise the archive.

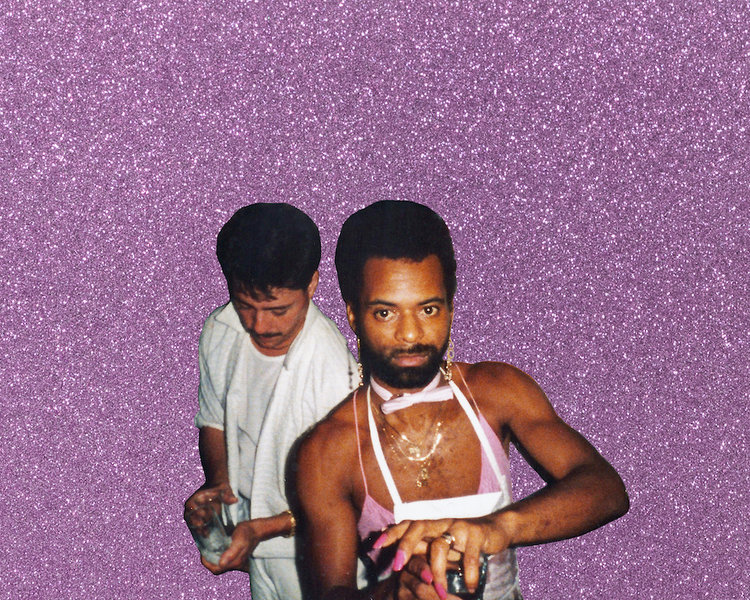

Starting this weekend through the end of June, Oakland-based artist Sadie Barnette transforms The Lab into The New Eagle Creek Saloon, an installation and ongoing series of public events that reincarnate the multiracial gay bar her father operated between 1990 and 1993. In addition to presenting archival material, and constructing a working bar—gilded with Barnette’s magpie eye for glitter and sparkle— the space will host screenings curated by The Black Aesthetic, a site-specific dance ceremony choreographed by Rashad Pridgen’s Global Street Dance Masquerade, and will even make an appearance in this year’s Pride Parade as a float.

Currently on view at the San Francisco Art Commission’s downtown gallery, With(out) With(in) the very moment brings together Bay Area-based artists who witnessed and participated in the waves of community activism that arose in the 1980s and 1990s during the worst of the plague years. Guest curator Margaret Tedesco’s selection is both elegiac and urgent providing one model for how art can make demands – for changes in conscience as well as ground conditions—in moments of crisis.