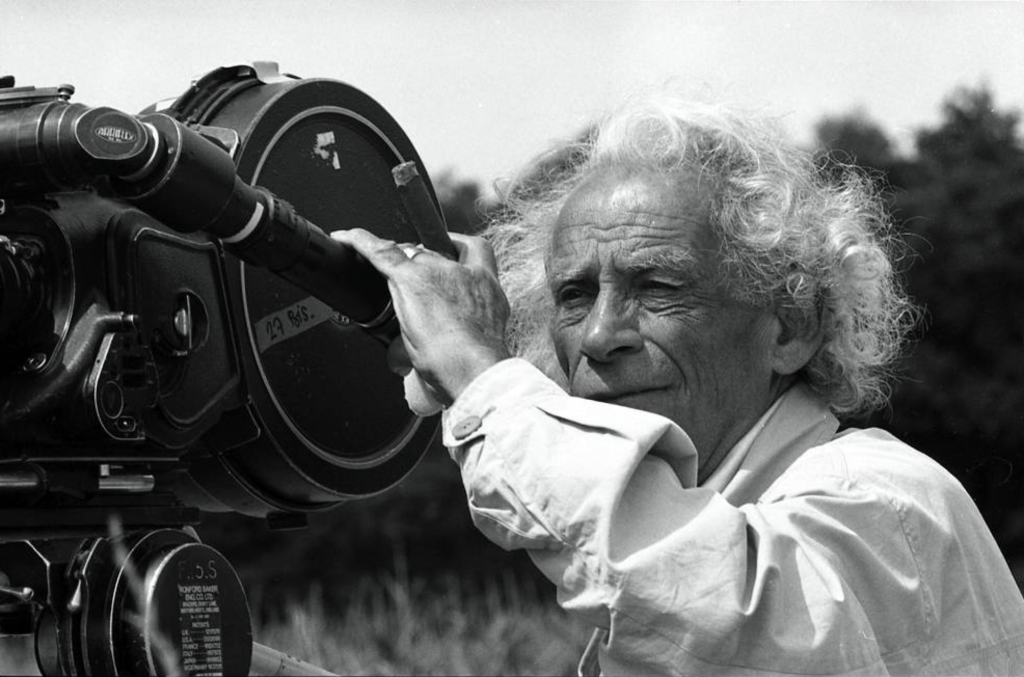

Calling all movie lovers and cinephiles, BAMPFA has concocted a remarkable month long retrospective of director Sam Fuller, one of the most subversive Hollywood auteurs of all time. The 10-film series entitled “From the Front Page to the Front Lines: The Essential Sam Fuller” (Fri/29-August 31) is showcasing nine 35mm prints (plus one DCP) and is the perfect chance for avid fans, along with new admirers, to be exposed to these mini-masterpieces on the big screen from the man dubbed “the Jewish John Ford.”

Including 24 feature films over six different decades (1949-1990), Sam Fuller’s unique filmography can be summed up by one of his most famous quotes, “Film is like a battleground, with love, hate, action, violence, death… in one word, emotion.” In his astonishing autobiography, A Third Face: My Tale of Writing, Fighting, and Filmmaking, he recounts his trajectory from paperboy to Hollywood screenwriter to cult filmmaker. In fact, the love given to his films, beginning in the 1950s, by French New Wave directors such as Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut, and Luc Moullet could be why he is still revered so much by later generations. This adoration even culminated into Godard giving Fuller a cameo in his 1965 film Pierrot Le Fou (1965).

So who was Sam Fuller? What makes his films (still) so incredibly resonating, and why should you do whatever it takes to attend BAMPFA for as many of these rare 35mm screenings as possible? When I sat down with Kate MacKay, associate film curator at BAMPFA since 2016, she immediately exclaimed, “He is one of my favorite filmmakers!”

While MacKay was doing the research for the 10-film series all the way back in 2019 (when it was originally going to screen), she realized that BAMPFA hadn’t screened Fuller’s films since just after his death in 1998, when they simultaneously screened at the Lumière Theater. She also stumbled across a sound recording of Fuller when he appeared for a talk at BAMPFA—there’s apparently even an actual cigar he left somewhere in the archive.

“To watch a (Sam) Fuller film is to be immediately pushed, face first into the hypocrisies and criminal fictions that make up the American Myth.” The sentiments of Ginger Varney of the LA Weekly is at the heart of why MacKay feels this series could be interesting to a first time viewer of Fuller’s work.

“Sam Fuller presented such a unique portrait of mid-century America through the genres of Westerns, Film Noir, and War pictures,” MacKay said. “Added to that, he and his films were very sincere, even with his tabloid sensibility. Which is interesting because the way audiences may have watched them over the years has been with a sense of irony.

“When you think of Quentin Tarantino, who is really influenced by Fuller, Tarantino’s films are kind of ironic and often don’t have the sincerity that Fuller had. Fuller believed in America. Believed in America’s most idealistic form and yet he’s also critical of the US’s failure to live up to its ideals. His heart was really in the right place and I am interested in how that will translate to modern audiences today.”

“He also was always the champion of the underdog, whether it be a petty thief, a sex worker, a foot soldier, or even a cop; he’s always on the side of people who are on the ground, dealing with the oppressive forces of totalitarianism. I really appreciate his affinity with regular people and I think he was able to maintain his vision and control over the studios, because he made his movies within the budgetary restraints of a B-movie. More than that, I find Fuller’s films to be sincere, efficient, passionate, and profoundly anti-racist.”

Nine of the ten features that screen in the series will be presented in 35mm. MacKay tracked down each of the prints from numerous archives across the country. “One of my favorite memories in general was when I projected a restored 35mm print of Pickup on South Street (1953) for the Cinémathèque Ontario in the early 2000s,” MacKay said. “I was just dazzled by the sharpness and density of it all, especially the famous scene in the subway; you could see every pore and every bead of sweat on Jean Peters beautiful face.” It should also be noted that Richard Widmark and Thelma Ritter are especially memorable in what the program states “is one of greatest film noirs of all time.” 35mm print (courtesy of George Eastman Museum) screens Fri/29 at 7pm.

The series continues with his first (of many) war films: The Steel Helmet (1951), a stunningly gritty exploration of American racism set (and made) during the Korean War. Fuller’s real life trials and tribulations in World War II play a huge part in his unromantic views towards war. (He landed on the beaches of Normandy, Sicily, and North Africa and even filmed 16mm footage of the liberation of the concentration camp in Falkenau, Czechoslovakia. The footage—known as V-E +1—was recently selected to be preserved by the National Film Registry.) The US Pentagon gave perhaps the greatest review for Steel Helmet upon its release, calling it “vicious and full of perversions.” 35mm print (courtesy of the Academy Film Archive) screens Wednesday, August 3 at 7pm.

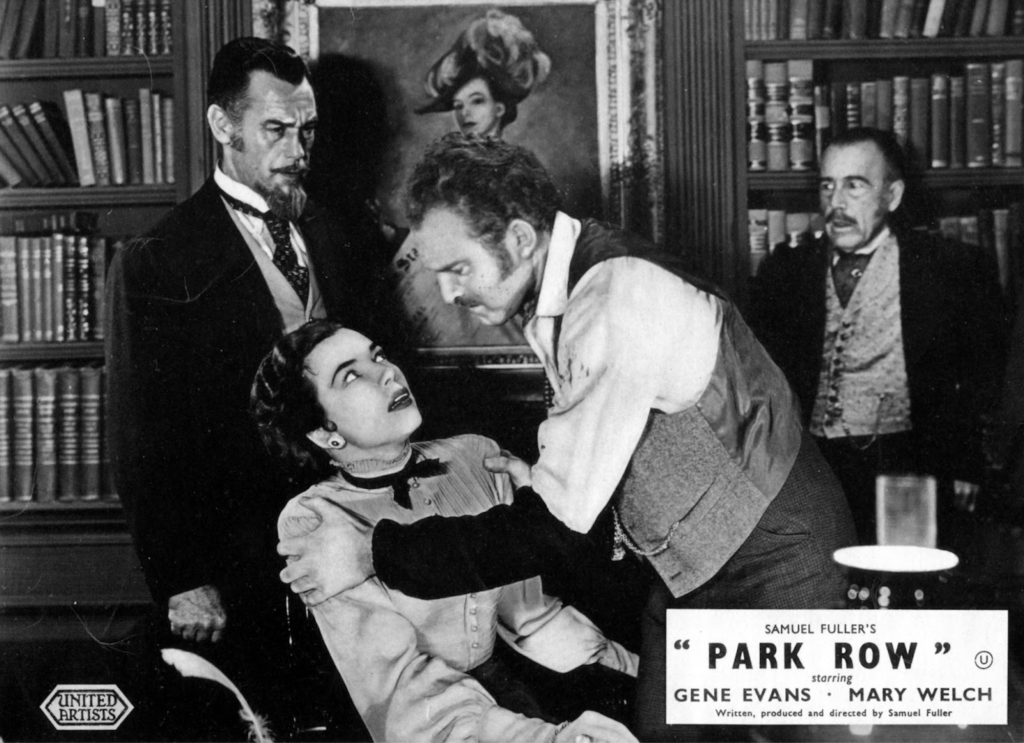

Even though Park Row (1952) is set in 1886, Fuller tapped into his earliest days of working as a newspaper copyboy at 12 and then graduating to crime reporting at the age of 17. Easily his most autobiographical film, Fuller stated that this was “the story of my heart,” embodying all the love, hate, action, and emotion he associated with the press. 35mm print (courtesy of Park Circus) screens on Friday, August 5 at 7pm.

House of Bamboo (1955) is an astoundingly brave film noir that not only exposes PTSD, racism and immorality among a group of American ex-soldiers, it was the very first postwar Hollywood film shot in Japan. Heavy hitting actors Robert Ryan, Robert Stack, and Shirley Yamaguchi (from Kurosawa’s 1950 film Scandal) are quite memorable as Fuller captures them in astonishing CinemaScope and DeLuxe Color on the streets of Tokyo. 35mm print (courtesy of George Eastman Museum) screens on Wednesday, August 10 at 7pm.

Barbara Stanwyck is absolutely mesmerizing in Fuller’s feminist Western Forty Guns (1957), in a performance that easily ranks alongside hers in Anthony Mann’s 1950 revisionist Western The Furies, as well as Joan Crawford’s turn in Nicolas Ray’s Johnny Guitar (1954). It also showcases one of the longest tracking shots ever done at Fox’s studio at that time, running almost three minutes long. This is the only film presented in a restored DCP (courtesy of 20th Century Studios/Criterion Pictures) and screens on Friday, August 12 at 7pm.

The Crimson Kimono (1959) not only kicks things off with a lurid bang (on par with Welles’ opening sequence for his own 1959 film A Touch of Evil), this heart wrenching film noir is decades ahead of its time as it tackles racial inequality and interracial relationships head-on. The movie was filmed on the streets of Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo and stars Glenn Corbett and Victoria Shaw, but it’s James Shigeta’s delicately nuanced performance that one may remember for the rest of their life. What’s even more powerful is how this 1959 film is still ethically trailblazing compared to most films made in Hollywood today. Don’t miss this 35mm print (courtesy of the Academy Film Archive) and screens on Wednesday, Aug 17 at 7pm.

Underworld U.S.A. (1961) is one of the deeper cuts in this 10-film series and is based on real articles from The Saturday Evening Post. It sports an utterly devastating performance by Cliff Robertson who plays a man who has been seeking revenge for the death of his father since he was a 14-year-old boy. Once he teams up with Dolores Dorn (a sex-worker named Cuddles), brace yourself for one of the most uncomfortably alarming film noirs of Fuller’s career. 35mm print (courtesy of the Academy Film Archive) and screens on Saturday August 20 at 7pm.

The Naked Kiss (1964)

Combining melodrama and purposeful camp, Fuller fully leaned into the salacious ’60s with this downright exploitation flick. Added to that is a truly neo-sincere performance by Constance Towers, whose character’s wild ways (from sex worker to orthopedic physician) have probably inspired more acting performances over the past 60 years than anyone truly realizes. 35mm print (courtesy of UCLA Film & Television Archive) screens on Wednesday August 24 at 7pm.

Shock Corridor (1963)

Continuing his cinematic shocking spree, Fuller reteamed with Constance Towers along with Peter Breck, James Best and Hari Rhodes to explore the explosive existentialism of the early-60s by way of a mental institution. Prophetically paralleling Roger Corman’s American International Pictures phenomenon as well as Miloš Forman’s Oscar winning One Flew Over a Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), this psychotic satire is something straight out of Gaspar Noé’s psyche. 35mm print (courtesy of UCLA Film & Television Archive) screens on Saturday, August 27 at 7:00pm.

Sam Fuller’s dream project The Big Red One: The Reconstruction (1980/2004) is a semi-autobiographical war epic, based on his own combat experience in WWII. Attempting to make the movie for more than 20 years (which would have starred John Wayne), Peter Bogdanovich helped set-up the production at Paramount. Lee Marvin (in one of his final roles) was brilliantly cast as the Sergeant, Mark Hamill (of Empire Strikes Back era) took on the role of Private Griff, a character who shows up in every single Fuller film, and a pre-Revenge of the Nerds Robert Carradine rounds out the platoon. Unfortunately the film was recut by the studio upon its original release in 1980. Thankfully, Richard Schickel and Bogdanovich did their best to reconstruct Fuller’s original vision in 2004, re-adding 47 minutes back into the film, based on notes left behind by Fuller, who had passed away at the age of 85 in 1997. Don’t miss this rarely screened 35mm print of the 163-minute reconstruction (courtesy of Park Circus) on Wednesday, August 31 at 7pm.

Jesse Hawthorne Ficks is the Film History Coordinator at the Academy of Art University in San Francisco, and is part of the San Francisco Bay Area Film Critics Circle. He curates and hosts “MOViES FOR MANiACS,” a film series celebrating underrated and overlooked cinema, in a neo-sincere manner.