By Zelda Bronstein

In recent weeks 48 hills has revealed that the Planning Department’s lax enforcement of San Francisco’s zoning laws has allowed the illegal conversion of hundreds of thousands of square feet of industrially zoned space into offices, thereby destroying scarce, irreplaceable venues for production, distribution and repair businesses and blue-collar jobs and squandering millions of dollars in development impact fees for Muni and affordable housing.

But it gets worse: The city’s so uninterested in enforcing zoning laws that nobody in the Planning Department seems to know or, care that a startup company inside a biotech incubator is making DNA-altered glow-in-the-dark roses in SoMa.

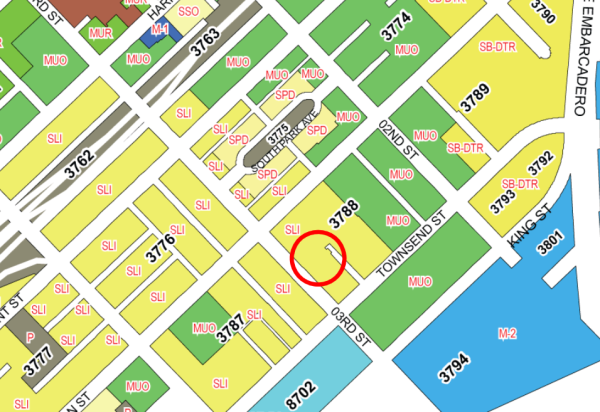

Situated at 665 Third Street, the biotech lab is in an area that’s not zoned for laboratories or life-sciences facilities. And it’s engaging in what is, to say the least, a controversial scientific practice, one referred to as “genetic engineering on steroids.”

Here’s the story:

Last October, the Planning Commission followed the Planning Department’s recommendation and legalized the longtime de facto unauthorized conversion of 123,700 square feet of light-industrial space at the Third Street site into offices. As we reported on June 9, the representative of the building’s owners told the commission that the building had been occupied by office users since the 1980s. Neither that representative nor planning staff said anything about biotech or genetically altered plants.

According to its website, the lab facility, Biosciences Laboratories, was established by MandalMed, Inc., one of the resident firms, in 2005. Today it’s “a 5,000 square foot facility in a remodeled warehouse [in] the South Beach neighborhood of San Francisco that provides shared laboratory space, equipment, and management for virtual and early-stage life science companies.”

The 665 Third Street building is in the Service/Light Industrial (SLI) Zoning District, and neither laboratories nor life science facilities, defined in Planning Code Sections 890.52 and 890.53, appear as permitted uses in the SLI table. The city considers any land use that’s not listed or referenced in a zoning district table to be prohibited.

The incubator’s founder, president and CEO, Constance John, a pharmacist and scientist, told me in an email that MandalMed moved into 665 third Street in March 2006. After finding the space, she wrote,

I contacted the City department that deals with zoning to determine if a life sciences laboratory could operate at our location. I was told that life science laboratory was permitted at our location at that time but that changes were being considered and thus zoning could change in the future. I was also assured that if the zoning ordinances were to change in the future, the City was not in the practice of making businesses move that had been properly operating at their location previously [emphasis in original].

The city was indeed considering a change in the zoning—from SLI to Urban Mixed Use-SOMA (UMU-S). But the proposed rezoning, which was never approved, had nothing to do with life-science labs and would have no impact on her business.

More to the point, since its enactment in 1990, SLI zoning has never permitted life-science laboratories.

I asked John if planning staff gave her a document showing that her lab would be a legal use at 665 Third Street. She said that they did not.

I also contacted the owner of the building, James Schafer, a general partner in the real estate investment, development, and management company Samuelson Schafer. Schafer spoke to me from his office in Kentfield. I asked if the Planning Department had told him that the Third Street building housed a biotechnology lab in an area that’s not zoned for it.

Schafer replied: “We have just gone through an extensive three-year process with the city and county of San Francisco. Every single use in that building was vetted by the city,” which “has a complete list of all the tenants.” Planning staff, he said, visited the building, and last October the Planning Commission approved the conditional use permit for which he had applied. That permit, said Schafer, allows every use that’s currently there.

But the permit authorizes office use. It says nothing about laboratories or life-science facilities.

After speaking with Schafer, I visited the Planning Department and examined the material in the binder for 665 Third Street. The binder contains 29 leases and a list entitled “665 Third Street Partial Office Lease History Evidencing continuous office use since 1967 when at least 33,760 gsf of office space was legally established by Building Permit No. 8706260” (Note: the issuance of a building permit does not legalize a use). The most recent of the 29 leases was issued to Nerdwallet on January 9, 2012. Nothing in the binder about Bioscience Laboratories.

I also queried the city’s zoning administrator, Scott Sanchez, asking if the permit allows laboratory or life science uses at 665 Third Street.

Sanchez replied:

I do not believe that this question has been raised before, but on first review it would appear that Laboratories and Life Science Uses are not permitted uses within the SLI Zoning District because they are not specifically listed as permitted uses. I’m not familiar with the use in question (at 665 3rd Street) and whether it would be categorized as a lab, life science, or office use.

Genetic engineering on steroids

What’s concerning isn’t just the dubious legality of the biotech incubator at 665 Third. It’s also the kind of work that’s being done by some of Biosciences Laboratories’ subtenants. Of the nine start-ups listed on the firm’s website as current clients, two—Cambrian Genomics and Glowing Plant—are practicing synthetic biology.

In a story about Glowing Plant published in the Seattle Times last October, Ariana Eunjung Cha described synthetic biology as “genetic engineering on steroids”—an emerging field that

lies at the intersection of biology, engineering and computational bioinformatics…While genetically modified organisms (GMOs) are created with DNA from natural sources, the products of synthetic biology are often brought to life with DNA sequences invented on a computer.

In other words, today new life can be—and is being—coded.

Unsurprisingly, synthetic biology is controversial.

It could benefit humankind—yielding new drugs, destroying cancer cells, repairing defective genes, breaking down pollutants, detecting toxic chemicals, generating hydrogen for a post-petroleum economy (the list comes from a 2006 article by Jonathan Tucker and Raymond Zilinskas in The New Atlantis).

It also involves unprecedented risks. “[Be]cause engineered micro-organisms are self-replicating and capable of evolution,” wrote Tucker and Zilinskas, “they belong in a different risk category than toxic chemicals or radioactive materials.”

Synthetic biology carries another novel risk: it’s based on information, whose transferral is well-nigh impossible to control. As Laurie Garrett observed last year in Foreign Affairs:

Code can be buried anywhere…[A] seemingly innocent tweet could direct readers to an obscure Internet location containing genomic code ready to be downloaded to a 3-D printer.

Even so, Garrett says, the national and international authorities could do a lot more to regulate synthetic biology, which now has scant government oversight.

And then there’s synthetic biology’s unprecedented cheapness. “A generation ago,” Cha noted,

manipulating an organism’s genes required millions of dollars in sophisticated equipment and years of trial and error. Now it can be done in a garage with secondhand parts ordered off the Internet. Thanks to advances in computational power, the cost of reading one million base pairs of DNA (the human genome has approximately three billion pairs) has fallen from upward of $100,000 to six cents.

The upshot: entrepreneurs can now “enter the field with minimal investment.”

DNA, from a printer

Cue Glowing Plant. The infant company’s long-term goal is to use synthetic biology to mass produce luminescent plants that can be used for lighting. Last year it raised $484,013 on Kickstarter in a mere 44 days. The money went to designing a DNA sequence on a computer, making the DNA using a DNA laser printer, and then inserting the DNA into plants with a gene gun.

This was the first crowdfunding synthetic biology campaign on Kickstarter, and it raised both cash and contention. After failing to stop the fundraising, the environmental watchdog ETC Group posted an online petition to stop the unregulated release of the bioengineered seeds that was signed by almost 14,000 people.

Kickstarter subsequently announced that it was banning genetically modified organisms as rewards to future donors, “putting such gifts in the same category,” Cha wrote, “as drugs and firearms.”

That didn’t faze Glowing Plant. As company founder and CEO Antony Evans told the Wall Street Journal in this 2½ minute video, posted online in May 2014, producing plants that are bright enough to be used for lighting is “definitely not something that’s going to happen overnight.” For now the business is selling individual plants to home consumers. More precisely, it’s selling T-shirts, a label, and a book.

But you can pre-order a pack of 50-100 fertile Glowing Plant seeds ($40, expected to retail for $70), “an actual glowing Arabidopsis plant, already grown and ready to show off” ($100—“expected to retail for $150”) and a glowing rose ($150—“Please note that we have not yet decided what color rose this will be”).

For the more horticulturally ambitious, Glowing Plant offers a “Maker Kit” ($300) whose contents include:

-

Full instructions for how to make a glowing plant

-

Copy of the coffee table book with visual description of what you need to do

-

A vial of Glowing Plant DNA

-

Pre-poured LB plates (2 plates)

-

Arabidopsis seeds

-

Agro-bacterium

-

Small pot and soil

-

Silwet

-

Nutrient solution

-

Petri dish for germinating seeds

Note that in addition to the kit you need to supply bleach, ethanol and dry ice which are all cheaply available from your local drug store.

This item will ship in Fall 2014, your credit card will not be charged until then.

The presence of Bioscience Laboratories at 665 Third Street is no secret. In March 2013, under the headline “Slideshow: Inside Bioscience Laboratories’ South of Market Incubator,” the San Francisco Business Times posted an article-cum-photos that gives readers a peek inside the company’s quarters.

And, its ample national coverage aside, Glowing Plant is featured in the cover story of the Biz Times’ July 20, 2014 issue, “Bio Hacking Comes of Age.” Reporter Ron Leuty calls the business “the closest” thing to “a DIY biotech Steve Jobs—someone who [sic] biohackers can hold up as the archetype of the biohacking entrepreneur-cum-billionaire.” Antony Evans provides the pull quote: “There’s this world out there where it’s as easy to build a biologial [sic] app as a social media app.”

I asked Evans about the potential dangers of synthetic biology. “We’ve been through extensive discussions with the U.S. government and the USDA, and professional groups,” he said, “and none of these groups have raised significant concerns about what we’re doing.” Evans dismissed criticism of the field: “Most of these views are from people with an anti-capitalist agenda, not a scientific grounding.”

You’d hope that San Francisco officials would be keeping a close eye on the private biotech firms operating in the city (UCSF monitors campus biotech) and on the handling of genetically engineered material. If so, such oversight is not readily evident.

The website for Mayor Lee’s Office of Economic and Workforce Development provides detailed information about the tax credits available to biotech but says nothing about monitoring. My queries to OEWD’s Program Overview and Biotech Industry Liaison, Natosha Safo have gone unanswered.

The other OEWD staffer associated with the Biotechnology Payroll Tax Exclusion Program, Health Program Planner Sneha Patil, told me she doesn’t know whether the city does any such monitoring and forwarded my query to her colleague at the Department of Public Health, Public Information Officer Nancy Sarieh, whom I’d already contacted.

Sarieh responded promptly but didn’t know about biotech monitoring either.

Then John informed me that her lab has been repeatedly inspected by the Hazardous Materials Unified Program Agency of the city and county of San Francisco. I passed that information on to Sarieh and asked her to provide documentation. She said she’d submitted my inquiry to the Environmental Health Department and would get back to me with their response.

Two weeks later, Dr. Johnson Ojo, apologizing for the delayed response, emailed me that “there are some businesses at 665 3rd street that meet our criteria for hazwaste and hazmat for inspection,” but that the city doesn’t inspect biotech or “genetic material synthesis.” Dr. Ojo recommended that I contact Cal/OSHA.

On July 9 I spoke with Peter Melton of the California Department of Industrial Relations. Pointing out that his agency’s mission was worker safety, Melton told me that “inspecting new businesses” wasn’t a “routine” assignment for his colleagues. What puts something on their radar, he said, was either an accident or a complaint. After getting my message, he looked over Cal/OSHA’s records and “didn’t find anything on Glowing Plant.”

And what about the Planning Department? When its staff prepared the file on 665 Third Street last year, did they look at the tenants’ list in the lobby? Did they notice Bioscience Laboratories? Did it occur to them to check the Planning Code to see if labs are permitted at this address?

Now that they know it’s there, will they make any effort to see that the tenants of 665 Third are in compliance with zoning laws?

Or is San Francisco the Wild West of zoning, where anything goes and there’s no sheriff in town?