Out of the fog comes a little white bus

It ferries us south to the technical mouth

of the bay. This is biopharma. Double Helix Way.

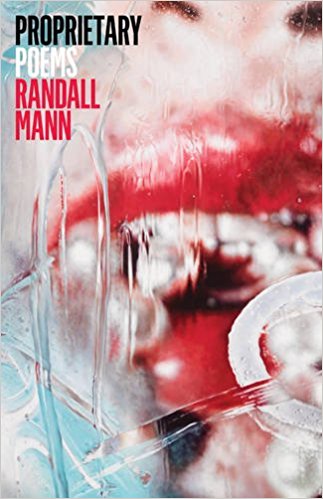

So starts the unnerving “Proximity,” from local poet Randall Mann’s fourth collection, Proprietary, released this week from Persea Books. (Mann reads with fellow poet Alex Dimitrov at City Lights, Wed/15 at 7pm.) The speaker sits “seven boxes below the CEO on the org chart” in “an office that faces the hallway” where “calendar is a verb.” Eventually he convinces himself to take a walk through the leafy trees near Building 5. “It might be nice to lie and watch the smoky/ marrow rise and fall, and rise. Don’t shut your eyes.”

Like most of Mann’s poems, this one is pretty autobiographical: He worked at Genentech for a decade, a sly recorder of corporate biotech culture and its surreal doublespeak, filling his notebook with the language that would become Proprietary‘s poems. “Once I figured out how to write about it, how to leach a poem out of it all, it was time to let go and move on,” he told me over the phone, referencing his recent severance from the company.

Proprietary is full of contemporary Bay Area markers, transfigured by Mann’s delicate turns of phrase and moody intrigue: CFOs asking to “loop back with you,” crickets chirping on Divisadero, realtors overselling Ocean Beach-front property, a “parliament of scowls at the Owl Bar,” strange feelings of being followed over Carquinez Bridge.

As in his previous books, Mann’s sensitivity as a gay man and poet in a rapidly changing city and rapacious global economy take center stage (there is a poignant sestina about fisting — a fistina?), but this time the language is shot through with sometimes hilarious, sometimes heartrending corporate-speak. Proprietary is an excellent gauge of what it feels like to live in San Francisco — or at least what it recently felt like, until the presidential election knocked everything into a different dimension.

I talked to Mann over the phone about rhyme and reason, pornography and gentrification.

48 HILLS I think of you as kind of our bard of the emotional and metaphorical effects of “techiness” on San Francisco, how corporate language can rule over relationships. You use so many of the elements of what has been happening, but you never sentimentalize them or allow them to become moralistic symbols.

RANDALL MANN For me there is a real ambivalence, in particular when I was working for biotech companies: I’m in the middle of an economy that is increasing the disparity between rich and poor, and pushing out what are also “my people” — queer artists. There have been lots of times when I’ve felt like the last poet standing in San Francisco. And that’s not true, but sometimes it can feel like that.

Writing about the language that people use to traffic in the world of San Francisco now is a way for me to address it and to cope with it. This has been a bracing few years, when all the changes have been so apparent, and I’m not on board with what’s been happening. But there’s no real poetic utility in just coming out and saying how I feel. Proprietary is a book about gentrification and ownership, that’s why I called it that. It involves the gentrification of language and this fatuous idea of ownership, of a house, of a relationship.

Right now in our culture everything is so fluid, it’s quite destabilizing. In many ways these poems are my way of dealing with this particular moment. For me, the power is in the presentation of what’s happening, filtered through a sensibility — some resignation, a determination to engage with what it means to be someone living through this time. But I don’t necessarily want to heap my judgement onto the poems because that would break them, or at least smother what they’re trying to communicate on their own.

It’s important to me as someone who has lived in San Francisco for almost 20 years and who has worked in a global matrix corporation for a decade to just put the information out there as clearly and as nuanced as possible. I have seen the inside, and I have been a part of the outside. And here is the information about it all, almost more reporting or leaking than swooping in with some grand gesture.

Everything is already so problematic, it’s so hard to separate yourself from the tools of late capitalism — like us recording this conversation over an iPhone — that really the most important thing I felt I could do right now in a poem is just get the information out there.

48H Proprietary is remarkably cohesive in tone and form — it feels more of a piece than your previous collections. For instance, a lot of the poems seem guided by internal rhymes, in a loose formal way that recalls one of your mentors [late San Francisco poet] Thom Gunn, who figures into one of the book’s poems. The poems are very lyrical, but never devolve into sing-song, despite some of the corporate baby-babble. How did it all come together?

RM The book was largely written from 2011 to 2015 — although there’s one poem, an elegy for Prince called “Alphabet Street” that came unexpectedly, of course, last year, but seemed to fit into the book’s overall structure.

I think the evolution of my formal choices really center around rhyme. Overall there’s more free verse in this book, but I’m using rhyme as the chief poetic driver, leading me from one image or through to another. I’ve found that as I’ve been writing, I love rhyme more and more — I’m completely addicted to it, that wonderful way that rhyme can push a poem forward and also turn it back on itself.

People sometimes have a reaction to rhyme, they discount it or consider it somehow archaic or “high poetic.” My response is often that our culture, at large, is in love with rhyme. Songs, advertising… i just think it’s funny that something so steeped in our everyday culture, so central to it, can seem so alien once it’s isolated. For me it’s a content generator, a way to help me feel through the dark of a poem. I’ve been writing seriously for 25 years, and writing is still a great joy because it’s a puzzle. Rhyme is an integral part of the momentum of that.

48H One of your main subjects from the beginning has been contemporary gay love, and how it’s experienced, reflected and refracted, through different media and situations. In “Secondment,” you log onto the Planet Romeo hookup site from your European hotel room, where “a torso wrote: I want to dress/ you up like Norway, and invade.” In “Flagging,” you summon the foreign-yet-familiar feeling of finding yourself in a leather bar where people are actually wearing leather — a real rarity these days, as if you had wandered into a 1970s dream.

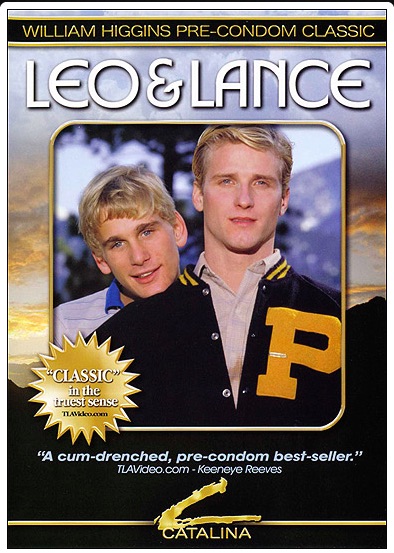

I think one of the poems in this collection, Leo & Lance, which references a classic gay porn from the ’80s everyone from that era seems to have seen, will ring a lot of bells for gay men of a certain age: At 17, you nervously buy it from the porn section of the neighborhood videostore, along with a bisexual flick to try to save a little face with the clerk, spending all your allowance on the VHS cassettes. (“Can anyone even/ remember how hard-/won a little corner/ of sex was then? No internet …”) But then you jump ahead a couple decades, now using the internet to find out what happened to the eponymous bleach-blonde boys, who both met pretty tragic ends within a year of each other.

RM That poem is very autobiographical — I did buy my first porn VHS in Orlando as a teen, and it was expensive! One of the things I’ve been thinking of lately is turning back a little bit to the time — I’m 45 now — where I and maybe people my age had to figure out their sexuality without access to very much information, and it was a fog. The fog, and the figuring out in almost complete darkness, was a real struggle, with little bits of sexual information dangling, like Cruising, or the underwear ads in catalogs, a porn mag glimpsed in a bookstore, or this or that.

So I wanted to capture that. David Trinidad has a poem about the porn star Dick Fisk (“Ode to Dick Fisk“) where David talks about his relationship and what’s happening in his life, but then he starts talking about Dick Fisk, so there’s this intertwining of autobiography and pornography. I really liked that form as a way so many of us could probably tell the story of our sexuality. But then as I was watching Leo & Lance again, I became curious about what happened to them, and telling their story after they had moved on from the porn seemed another way to tell that sexuality story, to continue it.

48H The poem Leo and Lance contains a tear-jerking image, of this beautifully open-ended moment in the porn when, out of nowhere, Leo and Lance have a giggly snowball fight and are just two young men having fun. The porn was made in 1983, and it’s shocking how, with AIDS, the thought of young gay men smiling and enjoying their bodies is so shadowed by sorrow.

RM The snowball fight was so innocent, and just so moving. I thought about what it meant for a young boy to watch this porn and was like, ‘OK, well if they’re having sex, and having fun, then that sort of validates my confusion and my existence.’ I love the paradox — that porn, which is not so innocent, connected so much in gay context with innocence. And it all connected in a way. It’s the longest poem I’ve ever written.

48H What about everything that’s happening now, since the last election? How do you think that will influence your writing, now that it seems we’re dealing with a political and historical disaster that kind of dwarfs some of the debates of the recent past?

RM I do have an anti-Trump pantoum — I think a lot in pantoums — coming out. But I also have another pantoums that simply repeats the mean things an ex-boyfriend said to me over and over in different ways. So my writing is still political and personal. I’m still writing about the gentrification of this town, as well. They say that poets write the same fucking poem over and over and call it art. [Laughs.] It looks like lack of love, brutality, and the changing city are my eternal subjects.