SCREEN GRABS Entertainment-industry legends seem to be dropping like flies these days, underlining the fact that luminaries of the 1960s and ’70s are well into their dotage, while survivors from the preceding Hollywood-and-beyond “golden age” are very few now. One of the latter, fabled French actress Danielle Darrieux, just passed away at age 100, having scarcely retired from a screen and stage career that occupied about eighty-five years of that century. Olivia de Havilland (101) is still around, if long-inactive. (Apart from suing over her representation in the cable series Feud, that is.) But otherwise, one can scarcely think of any prominent names from the deep B&W celluloid past who are still alive and kicking, however feebly.

There’s a certain memorial aspect to the fourth edition of “The French Had a Name For It,” which plays a packed long weekend at the Roxie Fri/3 through Mon/6. In part that’s because three films are specifically included as homage to the great Jeanne Moreau, a figure at least as important to the Nouvelle Vague as Darrieux was to earlier French cinema epochs, and who died this summer at 89. But then all of these programs from programmer Don Malcolm and his Midcentury Productions are largely a testament to a national film industry that is no more, in which genre films—good, bad, indifferent, sometimes inspired—could be cranked out in bulk for audiences that most often simply went to “the movies,” rather than needing to be sold on a particular title.

The term “film noir” was duly invented in France to describe American crime movies of the 1940s and ’50s. But as these series have demonstrated, it could be applied equally to many French productions of that period, albeit with a broader brush that encompassed more diverse kinds of melodrama than are usually associated with American noirs. This fourth “Name” collection expands the category further to embrace films made as early as 1935 and as late as 1966, plus a couple made by foreign directors (England’s Tony Richardson, German-born Hollywood veteran Robert Siodmak). There are also movies by such internationally known Gallic talents as Robert Bresson, Marcel L’Herbier and Claude Chabrol, of whom only the latter is (in his idiosyncratic way) associated with noirish subject matter.

Well before Hollywood began eschewing old-school glamour for new types of movie stars (mold-breakers Brando and Dean aside), Moreau represented something edgily modern on screen: Complex, at times neurotic, communicating frank sexual appetites without being a stock “sexual object,” alluring sans conventional beauty, her evident intelligence a challenge to assumed male superiority. (She never made sense in suffering, passive heroine roles.) Though oddly she never worked with Chabrol, Moreau’s inherent air of moral ambiguity made her a natural for the noir-style narratives that drove many of her best-known vehicles, including Louis Malle’s Elevator to the Gallows, Vadim’s Dangerous Liaisons and Truffaut’s The Bride Wore Black.

In the 1966 Mademoiselle, the new Roxie program’s final film (and chronologically its last as well), she plays a figure of pure, almost cartoonish malevolence—an imperious rural schoolteacher and secret pyromaniac first glimpsed in little black dress and incongruous high heels, traipsing around the countryside to flood a village by releasing its dam out of sheer spite. The primary target of this hostility is an all-male Italian emigre family that draws both her racist loathing and suppressed erotic desire.

Perhaps only Moreau could have played such a character without curdling into camp, though this astringent tale—one of several deliberately off-putting subjects handled by Brit director Tony Richardson after the crowdpleasing triumph of his Oscar-winning period romp Tom Jones—was loathed by critics and audiences alike at the time. What did they expect? This wasn’t Henry Fielding; it was Marguerite Duras adapting Jean Genet, a recipe for perverse discomfort if ever there was one. Two earlier features being screened offer episodes from Moreau’s pre-stardom screen apprenticeship: As an ingenue in Hi-Jack Highway (1955), and a gangster’s moll in The Strange Mr. Steve (1957).

Another legendary French star, Jean Gabin, overlapped with Moreau—they appear together here in Hi-Jack Highway aka Gas-Oil —but was beginning to seem a relic by the time of her ascent. Gabin was at his greatest in the 1930s. By the ’50s, he too often seemed bored, his performances as stolid as his vehicles (popular as they remained) were uninspired. Still, some are solid films in their own right.

One such is Crime and Punishment, a loose 1956 update of Dostoyevsky’s novel. The real star is fifth-billed Robert Hossein, the compelling, still-living (albeit retired) writer-director-actor whose work was showcased in prior editions of the Roxie series, as the Raskolnikov figure. Gabin shows up late as the police detective investigating this impoverished student’s crime of murder. The interesting cast also includes gorgeous Marina Vlady, future leading director Bernard Blier (as a bourgeoise pederast), and future international star Lino Ventura. Yet like too many French films of its period, it’s overly talky and square.

Fellow prewar luminary Darrieux co-stars in a third Gabin feature, The Night Affair (1958), though here his gendarme’s attentions are directly mostly at starlet Nadja Tiller as a comely young drug addict. Both it and Hi-Jack were directed by Gilles Grangier, an underrated journeyman of the postwar, pre-Nouvelle Vague industry era. Affair has a bonus for jazz fans in the form of several numbers from Hazel Scott, the famed African-American singer, pianist, and activist who at that point had relocated to Paris, having been blacklisted for dubious ties to the Communist Party in the US.

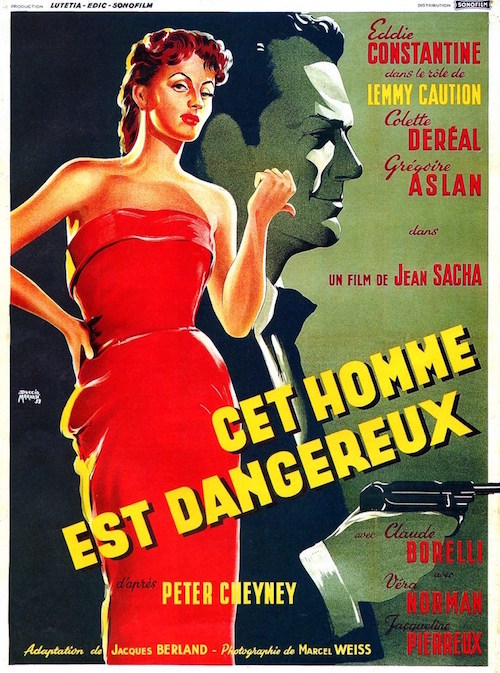

A third star spotlit here was of that odd species, the American actor who finds great fame abroad without ever getting much acknowledgement back home. An aspiring singer, Los Agneles-born Eddie Constantine ultimately found success not in that role but in its diametric opposite—as the tough, monosyllabic protagonist in umpteen Continental imitations of hard-boiled American thrillers. His signature character was Lemmy Caution, the glowering detective he played eleven times in vehicles variably loosely derived from British author Peter Cheyney’s pulp writings. Yet the only one that American audiences took much note of was a sort of parody: Godard’s futuristic 1965 Alphaville, which incorporated noir elements mostly to mock them.

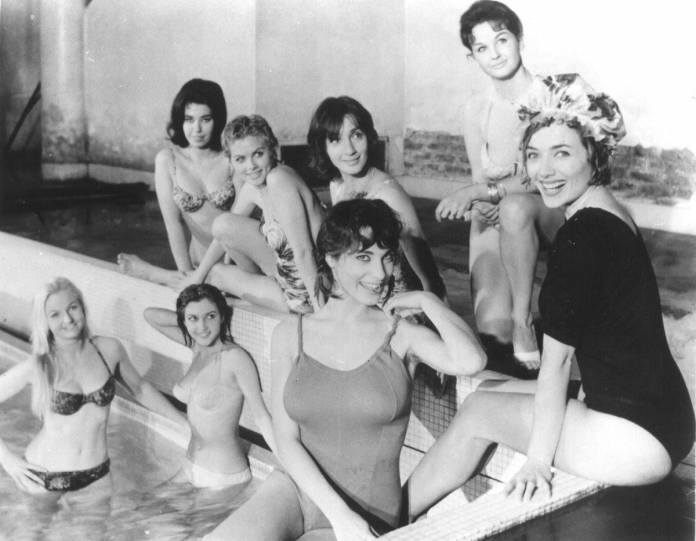

Constantine was so popular with European audiences, however, that a good share of his other movies simply cast him as “Eddie,” further blurring the line between performer and persona. Opening night on Friday, the Roxie offers a double bill showcase: First up is 1953’s This Man is Dangerous, his second outing as Caution, followed by 1964’s Lucky Joe, which expands his usual range by making him a hapless petty criminal shunned as bad luck by his own underground milieu.

Other notable titles within the 13 features “The French Had a Name For It” offers this go-around include early works by two great directors who had yet to fully realize their signature styles: A pair each from Robert Bresson (1958’s The Ladies of Boulogne Wood, 1961’s Gigolo) and Claude Chabrol (1958’s The Handsome Serge, 1960’s The Good-Time Girls).

Also of particular interest are two proto-noirs from the 1930s. One, Happiness aka Le Bonheur (1935) was a highlight in the long but mostly undistinguished sound-era career of Marcel L’Herbier, whose often wildly ambitious silent films (L’argent, L’inhumanite) have found new appreciation in recent years. Le Bonheur (not to be confused with the same-named Agnes Varda feature two decades later) stars glamorous Gaby Morlay, a major figure of the silent and early sound era. Today, however, the main attraction in this offbeat romance between a silver screen diva and an anarchist is leading man Charles Boyer, who’d already tried Hollywood (without much success) but is seen here on the brink of international fame.

The other, 1938’s Hatred aka Mollinard, showcased Harry Bauer—a great French star of the era who was tortured to death by the Nazis five years later—in one of a few Gallic films made by Robert Siodmak, who himself had fled his native Germany when Hitler came to power. Siodmak would soon move on to Hollywood, where he would make some of the greatest American noirs (The Killers, Criss Cross) in that genre’s peak era. One wonders what he would have thought if he’d known that nearly a half-century after his 1973 death, Nazis would again be on the rise… in the US, yet. Sometimes real life is blacker than even noir can imagine.

The French Had a Name For It 4 plays Fri/3-Mon/6, Roxie Theater, SF. $12-14 ($65 for series pass), more info here.