With our POTUS’ controversial-no-matter-who choice to replace Ruth Bader Ginsburg turning out to be a woman whose religious sect apparently really, really merits those Handmaid’s Tale comparisons, it seems an apt moment to reflect upon and value the gains of the peak Women’s Liberation Movement era about a half-century ago. Two new biographical dramas serve that purpose very nicely—or would, if only they were better.

The higher-profile disappointment is The Glorias, director Julie Taymor and playwright Sarah Ruhl’s adaptation of Gloria Steinem’s memoir. But to a degree, it’s more of a biographical fantasia in the realm of Todd Haynes’ Bob Dylan imaginarium I’m Not Here, with Julianne Moore, Alicia Vikander, and two young actresses playing guess-who at different ages, sometimes interacting with one another. There are other flights of fancy, too, amidst an otherwise rather pedestrian career highlight-reel featuring broad performances by Bette Midler (as Bella Abzug), Janelle Monae (Dorothy Pitman Hughes), and others as sound-byte-spouting fellow public figures.

But Dylan’s image and art lend themselves to mythification. By contrast, Gloria Steinem is just about the late-20th-century American personage of major cultural import least apt for confabulation: So much of her appeal always lay in an acute political intelligence utterly down-to-earth, disinterested in egotism or artifice. Thus probably no female director could have been less apt for this job than Taymor, a genius of the stage (most famously The Lion King) whose screen work (visualizing the Beatles songbook in Across the Universe, Kahlo in Frida, Shakespeare in Titus and The Tempest) has been more uneven. But in any medium, she’s as much decorator as director, like a less garish Baz Luhrmann; her work is about striking pictures, not ideas (or even storytelling or people, really).

When The Glorias plays to her strengths via fantasy fillips, the result seems entirely superfluous to the matter of Gloria Steinem. And conversely when it focuses on the real-world matters of journalism, protests, and legislative or workplace triumphs over ingrained societal sexism, it is uninspired inspirational cinema of a type Taymor has little facility for. Even such terribly on-the-nose recent feature statements of history made pop feminism as On the Basis of Sex or Hidden Figures had more dramatic impact than this 2 1/2 hour checklist of career peaks and strained up-to-the-moment wokeness. The Glorias (which begins streaming on Amazon Prime and digital platforms Wed/30) is like attending a party for someone you fervently admire, only to find the organizers designed an affair that’s somehow entirely wrong for the honoree’s personality.

What became the unofficial anthem of second-wave feminism was Helen Reddy’s “I Am Woman,” a #1 1972 single in the US and elsewhere. The expat Australian singer considered herself a feminist, and wrote (well, co-wrote, with fellow Aussie Ray Burton) a great, specifically female empowerment anthem. But as ubiquitous as her distinctive vocals were on the radio through the mid-70s, Reddy is largely forgotten now. It was a pity she didn’t write more songs; more so that her taste in covers was on the schlocky side. Despite considerable commercial success, her talent ultimately seemed betrayed by mediocre artistic choices.

In Reddy’s own memoir The Woman I Am, she’s understandably somewhat bitter about the fact that despite all hit-making, she was unceremoniously dropped by her record label at Me Decade’s end, and the fortune she’d accrued wound up largely blown (in more than one sense) by the second of three husbands. Her adult children eventually had to buy the erstwhile “Queen of Pop” a Sydney apartment she could retire to. Nonetheless, the book has the salty determination of a born showbiz trouper; Reddy refuses to accept the role of victim.

That flintiness is just one of the things conspicuously missing from I Am Woman, director Unjoo Moon and scenarist Emma Jensen’s disappointingly bland, formulaic biopic. The problem isn’t that they lack the budget to fully limn the heights of their subject’s stardom—it’s that they’ve somehow made this pleasingly, unfussily self-assured woman seem a passive heroine in her own life. There’s too much emphasis on the marriage to coke-addled agent Jeff Wald (Evan Peters), and not enough to providing Reddy the force of character lacking in Tilda Cobham-Hervey’s otherwise competent performance. Adding insult to injury, the script often alters or ignores facts for no good dramatic reason, while mostly sidestepping Reddy’s vocals to have the actress lip-synch to an OK impersonator.

As with Steinem and The Glorias, Helen Reddy isn’t likely to get another such screen treatment soon—and while very loosely affiliated otherwise, both these women deserved much better. I Am Woman is available as of today via Rafael@Home and other streaming platforms.

When new movies disappoint, there’s always the comfort food of old movies, even those that were never intended to be comfortable. Among the latter is the first screen version of Richard Wright’s 1940 Native Son, a best-seller and ongoing classic that played a significant role pushing racial injustice into public awareness in the twenty-odd years leading up to the Civil Rights Movement. But as successful as it was, Hollywood wasn’t going to touch such incendiary material with a ten-foot pole—the occasional novelty musical aside, that mainstream industry would shy from all-black films for decades to come.

Thus it somehow fell to French director Pierre Chenal to make Native Son—in Argentina, yet, to which he’d fled the Nazis as a Jewish man during World War II. An adaptation had been a success on Broadway, directed by Orson Welles no less. It was planned that the play’s star Canada Lee would reprise his role as Bigger Thomas, whose doomed fate is sealed the day he accepts a job as chauffeur for a rich white Chicago family. But Lee was detained by authorities while making Cry the Beloved Country in South Africa. So Wright was forced to take the role himself, though he was no actor and knew it.

That was just one of many things that resulted in a clumsy, inauthentic, often poorly acted movie, with stilted dialogue and a ridiculously brassy score. Nonetheless, it had a certain amount of noirish style, and some of the source material’s inevitable power. A prestige production in Argentina, Chenal’s film was a hit there. But hopes for international success were dashed when it got severely cut and poorly distributed elsewhere. Even in that truncated form, Native Son riled McCarthy-era watchdogs, the trade magazine Variety pronouncing it “an underhanded stab at the US” that was probably Communist to boot.

Kino Lorber’s new Blu-ray restoration (which puts back all the footage long missing from most prints) provides an opportunity to re-evaluate a problematic but nonetheless important film. One would have hoped more liberal later eras would have done better by Native Son, but no: A starry 1986 version didn’t turn out very well, and HBO’s stab just last year was also a letdown. For better or worse, the 1951 film remains the only one Wright himself had direct involvement in. Sadly, he’d die in Paris just a few years later, too soon to see the great African-American political advances his work helped pave the way for. Native Son is currently streaming via CinemaSF, joined by Rafael@Home on October 9.

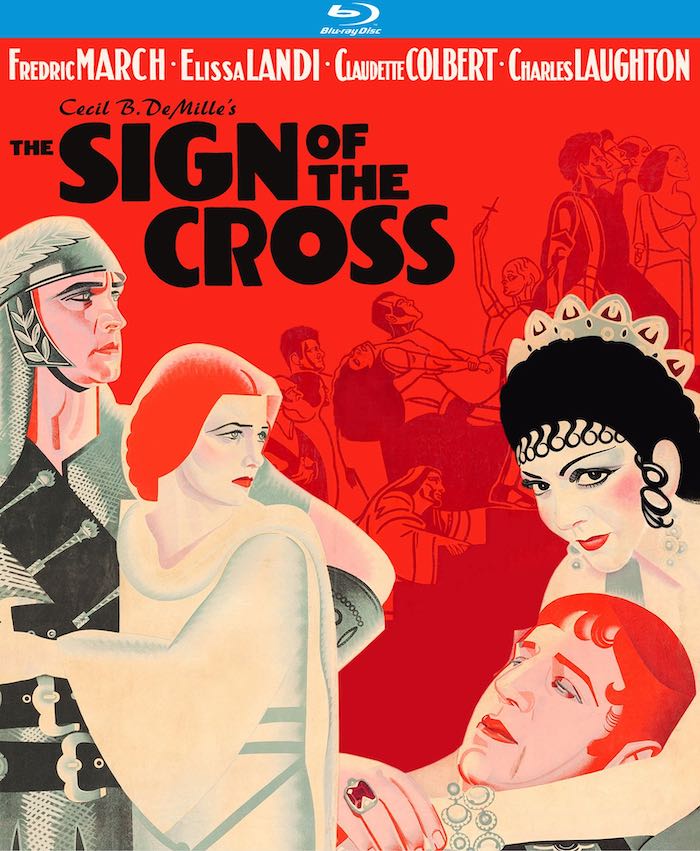

Moving from sincerity to silliness, Kino Lorber has also recently released to Blu-ray Cecil B. DeMille’s 1932 The Sign of the Cross, the only “pre-Code” period quasi-Biblical epic by Hollywood’s maestro of schlock spectacle. His biggest hits (among many) of the silent era had been pious, ponderous The Ten Commandments and King of Kings. After several early talkie flops, he returned to that formula for this lavish tale of 1st Century AD Rome, with Charles Laughton as a big baby of an Emperor Nero, chortling “Delicious debauchery!” when not throwing tantrums.

But the focus is on the duller likes of centurion Frederic March, who starts having reservations about all this “Let’s persecute Christians!!” stuff after falling for dewy Jesus worshipper Elissa Landi. Few exercises in Holy Hollywood have been quite so desultory about their inspirational content—March never even “converts” from paganism, his actions being solely motivated by having the hots for a Christian chick.

Fortunately, DeMille knew what audiences wanted—i.e. plenty of sinfulness to be repented of—and on that count Sign delivers. Its kitsch “ancient world” has peasants apparently from the Bronx speaking lines like “Hey, lookout where ya throwin’ those stones, willya?!?” A lady billed only as “Joyzelle” delivers a sort of lesbian hooch dance while uttering some dreadful “poetry” in a vaguely Yurrupean accent that belies the performer’s actual Alabama roots. Considerably more in on the joke is Claudette Colbert as Empress Poppea—famously seen bathing naked in “asses’ milk,” treating the whole vampy business like sophisticated comedy. (When March spits “You…harlot!,” Colbert grins and shrugs.) It was a turn scene-stealing enough to make her DeMille’s Cleopatra two years later.

All jaw-dropping is premature, however, before the real climax here: An orgy of slaughter in the arena, in which pagan spectators enjoy watching Christians get stomped by elephants, gored by bulls, mauled by tigers, molested by gorilla, and chomped by alligators. (Victims of the latter two scenarios are bound chorus girl types “clothed” only in strings of flowers.) As if all that weren’t enough, there’s also an interlude in which Amazon warrior women engage in deadly combat with dwarves. For all its ostensible go-go Christianity, this luridly racy Sign helped lead to the Catholic Legion of Decency’s censorious crackdown on the silver screen, which ensured that later reissues would be considerably cut.

DeMille didn’t protest; whatever made money was fine by him. He was, indeed, a man not only of his time but of ours: A highly active conservative Republican whose public and celluloid moralizing didn’t stop him from having a number of none-too-secret, long-term mistresses. Perhaps Sign of the Cross should be screened for our current POTUS—then he could actually answer that question about his “favorite Bible passage,” with “The part where the naked girl gets pawed by an ape.” Art imitating life!