The Board of Supes Budget and Appropriations Committee will hear a presentation Wednesday/7 on the city’s $216 million five-year plan for information and communication technology – and there’s a huge element missing.

The plan is largely about improving the city’s websites and access to information, which is great. Most of the items are things like $610,000 for a new police-officer scheduling system; sure, if we need that.

(My personal gripe: There’s nothing specifically about the Assessor-Recorder’s Office, which is too bad. That office used to have the best database for researching property ownership, landlords, taxes, etc, but the vendor they used has stopped its hosting and now the office has to create its own database. And it’s a shadow of what it used to be.

Since the physical office is closed, activists and reporters are out of luck if they want to track down property records. It used to be so easy; now it’s really hard. If an outside vendor could create a simple, user-friendly site, why can’t we?)

But there’s a much bigger problem with this plan.

The Committee on Information Technology acknowledged that this city has a crisis that goes beyond the city’s own online and cloud technology. From the report:

The digital divide has never been more evident than during the pandemic, and low-income residents, seniors, people with disabilities, and people with limited English proficiency in San Francisco are most at-risk. Only 59% of low-income San Franciscans have high-speed home internet connections and only 53% have basic digital skills, compared to 87% of all residents. There are also significant disparities by race, with 25% of Black and 22% of Latino residents lacking home Internet, compared to only 8% of White residents. Prior to the pandemic, this digital inequity prevented already disadvantaged populations from accessing the opportunities that technology provides, and the current pandemic has only amplified these challenges. Having quality devices, robust Internet connectivity, and digital skills are now urgent necessities to participate in society, and these trends will continue throughout COVID-19 recovery.

More than 40 percent of low-income folks can’t afford both a cell phone and the extortionate rates that private providers charge for broadband. That’s a lot of people.

Again, from the report:

The Department of Technology has led the way on Internet connectivity by providing free, high-speed Internet to over 5,000 households across 36 low-income housing communities.

That number in five years is supposed to go up to 15,000.

But only public housing and subsidized affordable housing projects get the service. There are tens of thousands of low-income people who live in private apartments who have no reliable internet access.

And yet: The report says the city has 280 miles of fiber-optic cable buried beneath the streets, to connect 400 city facilities. That could be the start of a system that would actually deliver what we need – public, affordable high-speed internet for everyone in the city.

When he was a supervisor, and briefly mayor, Mark Farrell suggested that the city should offer broadband as a public service, just like water. The idea got nowhere – because the likes of Comcast and AT&T bitterly opposed it, he told me at the time, and there was a high price tag, almost $2 billion.

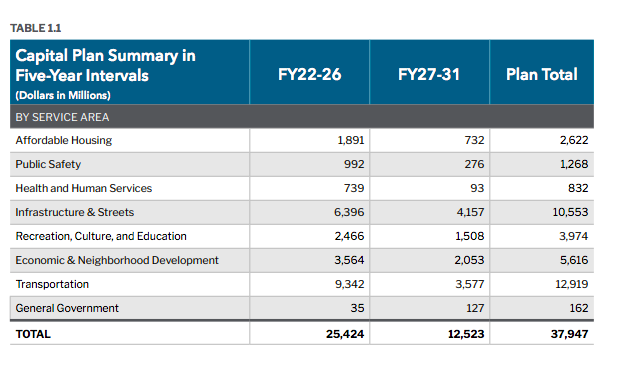

But wait. At the same time the committee will be talking about the COIT plan, they will be hearing the city’s ten-year capital investment plan, which calls for spending $37 billion on a long list of needs. Not a penny is listed for public broadband.

And this is different than, say, a park bond. A public broadband system, like a public-power system, would more than pay for itself over time. Let’s just do some simple numbers.

The interest rate on tax-free municipal bonds these days is about 5 percent. (Revenue bonds, backed by the venture, pay a little more but don’t require a public vote). That means if the city floated $2 billion in bonds we’d be paying back about $100 million a year, with interest, on a 30-year note.

San Francisco has about 365,000 households (and a whole lot more commercial offices, but let’s stick to residential service for now). Comcast and AT&T start internet service at about $50 a month, and that goes up after the first year.

Even at the starter rate, we’re talking $18 million a month, or $216 million a year.

The city could cut price that in half – to a truly affordable $25 a month – and still break even and pay off the bonds.

Yeah, we need maintenance and service, and that costs money – but add in the tens of thousands of potential commercial customers and this looks like a great deal. (No wonder Comcast and AT&T are against it.)

Broadband is as important today as other essential services. If the city treated it that way, we could solve the digital divide in a few years.

Farrell, who was among the most conservative supes (and a finance guy) told me back when he proposed it that this made perfect sense. He wasn’t even going to kick the private providers out of town, just offer (as we now do with CleanPowerSF) a municipal option. And then the private companies would have to lower their rates to compete – which would mean affordable internet service for everyone.

“I asked the folks from Comcast and AT&T what their problem was,” Farrell said. “Don’t they believe in competition?”

No, they don’t.

This is an incredible opportunity that the city is missing. In ten years, we’ll all look back and wonder what the hell we were thinking.

The hearing starts at 1pm.

The Public Safety and Neighborhood Services Committee will hold a hearing Thursday/8 on crimes targeting Asian American seniors. It’s an epidemic, and while some of these attacks have been reported, I suspect there are a lot that we don’t even know about. The attack on Ron Tuason went unreported until he found an old business card and called me. I’d like to see SFPD’s full set of data on this. The hearing starts at 10am.

The SFPD has had a problem for years with bad officers resigning rather than facing discipline – and then going on to get jobs in other police departments. (MissionLocal has a great piece on this here.) That also means that under a key state law, SB 1421, the records of their discipline are never made public, since they quit before the record could be completed.

At the Police Commission meeting Wednesday/7, Chief Bill Scott will present a new policy that starts to address the issue. Here’s the key phrase:

There is no sustained finding if the officer resigns or retires any time before the Commission or the Chief makes a final determination. If the Department continues its investigation despite the officer’s retirement or resignation, the charges will be sustained if the Department has made a final determination sustaining a finding and the officer has been afforded the opportunity to appeal.

In other words: If a cop breaks the rules and then quits before they can be held accountable, the department can continue the investigation, reach a sustained finding, and release the records.

It’s a start.