I’ve wandered into the Cantor Arts Museum many times over the course of my college career, sometimes to look at particular exhibitions, other times to meet people at the museum café. I’ve liked a lot of pieces there—among them a suspended wire sculpture by Ruth Asawa, a metal tapestry by El Anatsui, and of course, the Rodins—but there was only one that I made it a point to spend time with on every visit.

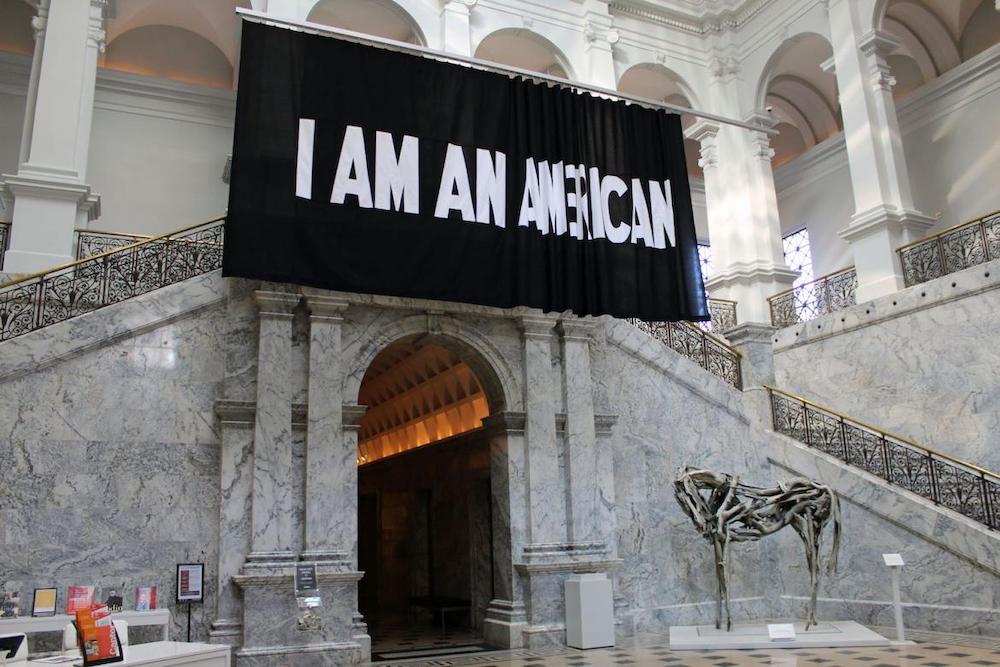

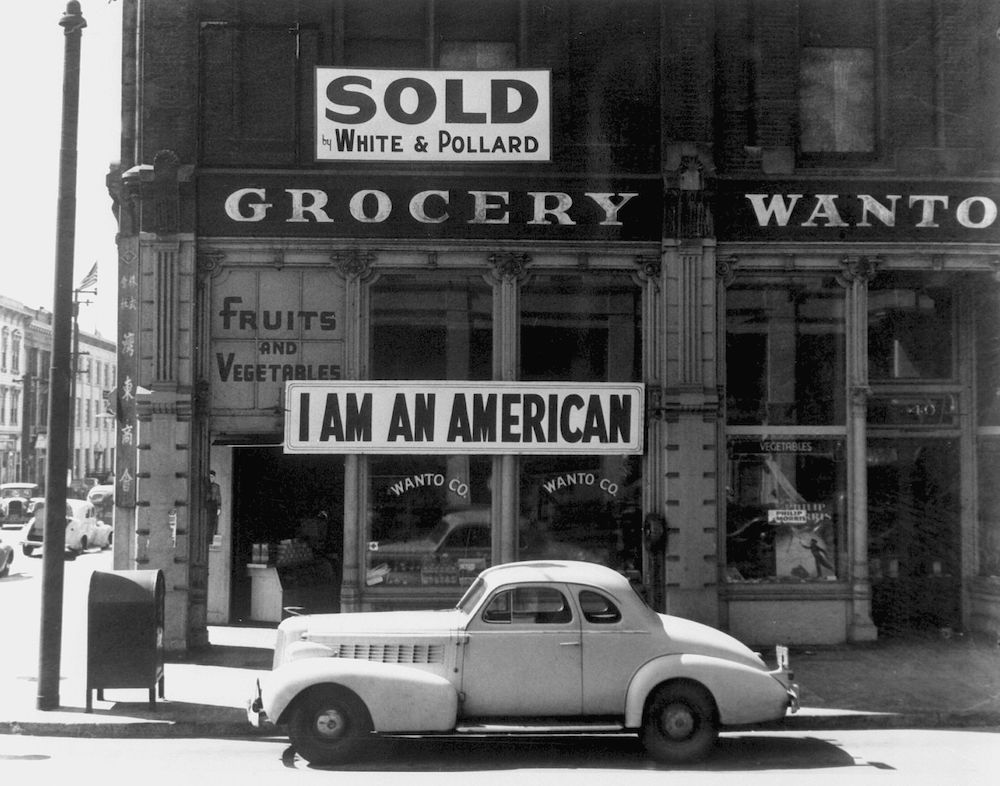

That was Stephanie Syjuco’s “I AM AN…” banner, which presided over the atrium. It quotes Dorothea Lange’s famous “I Am an American” photograph, which was taken in Oakland the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The storefront it captured was closed; Japanese-Americans had been ordered to evacuate large swaths of the Pacific coast. Syjuco’s banner hangs from a rod like a glorified shower curtain. The fabric is pulled to the left, the word “American” discernibly scrunched up.

On one tour, a guide asked us what we made of it. A curtain opening, one person said. A curtain closing, said another.

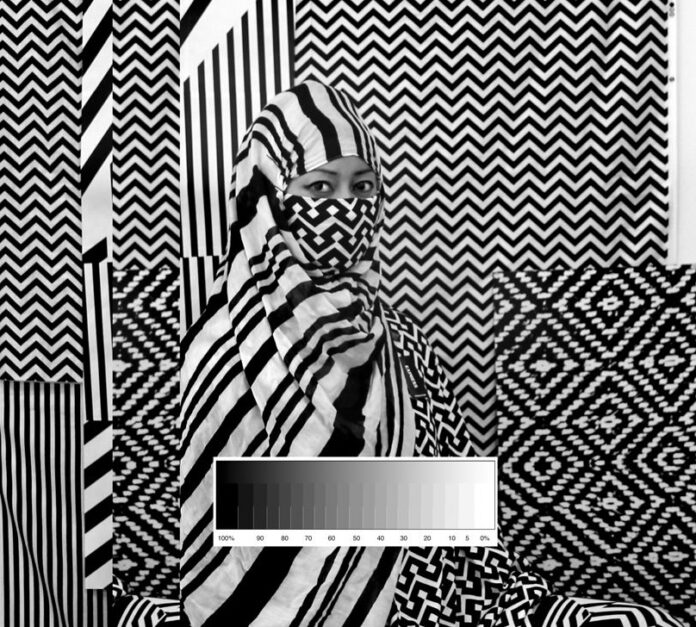

It wasn’t until I watched Season 9 of Art21, a PBS series spotlighting contemporary artists globally, that I came across more of Syjuco’s oeuvre. I was delighted and charmed by what was featured: a counterfeit goods crochet project, in which Syjuco invited artisans to crochet high-end designer handbags together; “Cargo Cults,” a faux-ethnographic photographic series that featured herself dressed in fast fashion apparel; and a set of hand-sewn chroma key American historical dresses. When I scrolled through her portfolio online, I kept feeling slight pangs of envy, the kind that strikes whenever someone does something clever you wish you had thought of first.

Given the political orientation of Syjuco’s work, I wanted to understand how she thought of her social practice and conceptual art in political terms. I reached out to the Bay Area artist, whose most recent show, “Native Resolution,” was reviewed in March by 48hills art critic Genevieve Quick. Here is the conversation that followed.

JASMINE LIU We can start by talking about conversation, which is the centerpiece of a lot of your art practice. You’ve stated in quite a few video interviews that one of the most important things for you is to simply stimulate conversation—whether that’s with your Mark Twain flag, your MoMA museum gift shop intervention, or that counterfeit booth at the Frieze Art Fair. And those are all such different pieces. Conversation is open-ended, and also therefore often a risky thing to engage in. My first question is, to what extent do you feel like you should have some control over how that conversation unfolds as an artist? What does it mean to you to be that person stimulating and maneuvering conversation?

STEPHANIE SYJUCO I’m glad you bring that up and frame it that way, because it’s neutral to say an artwork should be “about conversation,” or “this piece intends to stir conversation.” The truth is I actually have a pretty strong agenda behind the work. I’m trying to have my works be open enough that someone can enter it intrigued—something in it should prompt a question. But for me, it would be irresponsible to then leave it at being open-ended. My works do have a political position.

I’ve found that to draw people in, what they think they’re seeing may not be given immediately. In early works I’ve done, in which they were really overt political markers or slogans, I found that the audience already felt they understood what was happening, and so they wouldn’t necessarily enter into the work. Right now, I’m hoping that I’m creating things that are enticing, in which the audience wants to find out more, consider more.

I’m pretty upfront about my position personally, in terms of saying that I’m making work in opposition to white supremacy, from the standpoint of an artist who is thinking a lot about the lack of representation in American history and culture. It’s one of those tactical things where I find that unfortunately, there’s a tendency for the public to shut down and assume—especially from artists of color—what the work is about.

JL So if you have this political starting point that you want to be explicit about, how do you navigate around the possibility that the public might simply “shut down” in the face of your work?

SS I create work at different levels of legibility. Also, different works are made for different reasons. During the 2017 inauguration of the 45th president my work was directly involved in depicting a series of protests happening in reaction to it, including making protest banners and images of protesters. For me, that was a very direct reference to the political upheaval that was happening. But I’ve found that slogans often wind up being used to the point of potentially going unheard, and there is a lot of competition for public bandwidth.

JL What is the competition? Are there just so many slogans out there that putting out another one is not going to resonate?

SS One of the pieces that was in the Art21 project was a series of what appear to be illegible banners—protest banners that have this drippy text, or the banners look like they’ve collapsed on themselves and it was hard to read what was written. I wanted to make work about what I was literally seeing in terms of the visual upheaval and protest against the previous Presidential administration. That project in particular talked about the media manipulation of the message of resistance.

Remember the “both sides” phrasing used by the President, which was used to describe an equal platform for both white supremacists and anti-fascists? I was like, oh my God, no. It’s actually white supremacy versus human rights. It’s super clear! Yet we were handed the notion that both sides deserve equal deliberation.

I was using photographs of protest signs that I was seeing on the news—downloading those images and then using them as templates for how distorted the protest banners appeared. It just happened to be the way that the photos were taken, but what resulted was an inability to actually read the messaging. These were all banners made by anti-fascist resistors, who were painted—and are still painted—as negative forces.

There’s a lot of sampling and appropriation in my work that directly references images and ideas that are already circulating. I want to reposition them and present them in ways that hopefully open up a different meaning. That’s on purpose—to question the power structures that are in place.

JL That’s yet another way in which your intervention in the conversation is not neutral. You’re referencing and subverting through appropriation.

SS A lot of these things that I’m pulling from—especially that I AM AN… banner—are attempts to link a historical event with the present day. 2017 was a contemporary moment when people were again threatened with being rounded up, whether that was undocumented people or immigrants and refugees at the border.

That banner was originally made in 1942, by a Japanese American man under threat of internment. I’ve seen that slogan, “I AM AN AMERICAN,” resuscitated on t-shirts that Asian-American groups use, as a nod back to that original banner, which was photographed by Dorothea Lange and has had quite a lot of circulation. I’ve seen Asian-Americans pick it back up again as a kind of insistence of belonging.

People think that history is resolved, that we’re beyond what’s happened in the past, but these events keep recurring. So I wanted to make that direct linkage. People think, we’re safely not there anymore, we’re better people. We’re not. I want everyone to ask the question: what does it mean to be an American? What are our affiliations? What do we stand for? It’s very different depending on who you ask, right?

JL That’s a good segue to my next question. I really liked something you said in an interview, which was something to the effect of, if history itself is already fabricated, then I want to have a hand in fabricating it. I immediately thought of the work you did around hosting poster and banner-making workshops in San Francisco.

SS This was during exactly the same time as the work on the I AM AN… banner plus the CITIZENS portraits of anti-fascist protesters. That project you’re referring to is called Reap What You Sew, which was a direct response to the political organizing around the 2017 Presidential Inauguration. The work became a public resource on how to create protest banners. In those early days, a lot of people wanted to protest, but they didn’t know how. Folks felt unsure of how to proceed. Reap What You Sew was both a collection of templates and instructions on how to make fabric protest banners, with ideas, tips, and tricks.

It was also a public workshop series that was hosted by a number of Bay Area nonprofit arts organizations, who then invited people to come and bring materials and we would have a collective space to make these banners in the lead-up to anything from the Women’s March to just general protests against the federal government. It was surprising to see how people ended up using these kinds of things.

“The truth is I actually have a pretty strong agenda behind the work.”

JL I suppose you might not think that there’s that much of a line between your art practice and community organizing and being a citizen. But that workshop becomes a space where a lot of people who don’t necessarily identify as artists end up creating things. What does it feel like to you, as an artist, to see that engagement at play?

SS That dynamic ties in quite a bit to a number of my projects over the years. I’ve been a professional practicing artist for about 25 years and a number of my projects involve a collaborative or group activity—a social practice component. This could include the creation of workshops or a space in which people are invited to produce and distribute things.

Reap What You Sew was a temporary project. It was great for its moment but I stopped running the workshops because I became unsure about how critically engaged it actually was. Participants were producing a lot of messages such as “Love Trumps Hate,” “More Empathy,” “Love One Another,” and those kinds of things: feel-good slogans that in the end don’t get to the heart of what we are actually up against.

As a person of color, I don’t believe that more love and empathy is going to get us actual policy change. Having empathy for others is a personal transformation that people should go through to become better people, but I’m not going to wait around for someone to love or appreciate me to grant me human rights. To be very candid, I found a lot of white participants making these feel-good slogans, as if what was really the issue was that empathy would solve everything. I just don’t see that happening!

It has nothing to do with empathy—it’s the construction of racist exclusionary policies in order to accumulate capital and power. Loving people of color is not the heart of the issue. I found myself really frustrated by it in the end.

JL If I’m understanding you correctly, it started to feel more like a support group and not necessarily political organizing.

SS I don’t think it actually promoted political organizing, let’s just say. It made people feel better about expressing themselves and stating things that in the end, didn’t have much to follow up on with.

JL One thing that I wanted to get at by asking you about conversation had to do with precisely this tension around open-endedness: the possibility that open-endedness can get in the way of your initial goal. At some point, you lose a bit of agency over how the project unfolds. I guess this is a good example of that. When the project becomes more of an open forum, perhaps things don’t end up developing in the direction of your agenda.

SS Yes. But maybe that’s the nice thing about being an artist: I feel like I can be nimble. You put something out in the world, and if you realize it’s either not doing what you thought it was going to do or it’s not as complicated as you’d like it to be, then you have the ability to try again, or let it go and start something else.

JL Does this happen a lot? By trusting people and putting out questions, do you often run that risk of having that space be a bit hijacked by the direction other people take things in?

SS Yes, for sure. But at the same time, I’ve come to peace with it because different projects have different goals. So sometimes it’s a matter of attempting to communicate a really direct statement, and other times its attempting to play with subtlety or even contradiction.

There’s a project I’ve done called The Visible Invisible, which are a set of green chroma key dresses that reference American history. This project is actually, for me, about white supremacy, because I’m recreating iconic costumes or garments from pivotal moments in American history that are quite edited in how we were taught to understand them. Whether it’s pilgrims coming to America and “sharing” with the Indigenous people, or the Colonial Revolution, which is supposed to be about building a new democracy but was actually built on the backs of the enslaved as well as Indigenous extermination—there are all these contradictions in how American history is taught and what has been removed.

By making the dresses all out of chroma key green screen material, the idea is that American history operates just like a projection screen. The chroma key backdrop can be substituted for almost anything. Thinking and talking about white supremacy is acknowledging that it’s the invisible substructure of American history—invisible to some, let’s say.

But at the same time, I know that most people who look at this work will go, “oh my goodness! Look at these really amazing handsewn dresses!” and miss out on the cultural critique. Not everyone sees the same thing the same way, and as an artist of color I have to take into account that I make artwork that may or may not be legible to everyone depending on what they are used to taking their cues from. Is it a problem when a work about white supremacy isn’t immediately legible to white people as being about white supremacy, or does that perhaps expand a visual vocabulary about how white supremacy is actually seeped into everything?

“In no way am I trying to erase my position or heritage, but I also refuse to have it conscripted into a typecast role.”

JL So in a way, having certain people not see something about the piece is also what the piece is setting itself up to do.

SS Kind of, yeah. And then maybe upon further discussion, the motives become clear. But that’s also not necessarily meant to be the punchline. The work is about a lot of things. For me, the main motivation was the construction of white supremacy. Visible Invisible, the green dresses series, was for an exhibition at the Smithsonian Museum in 2018. That’s the other thing: I really wanted to make something that explicitly dealt with American history and put it in a national museum.

JL Can you talk a little bit about the genesis of the most recent project that you’ve worked on?

SS Native Resolution is a project that deals with the archives of the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian in Washington, DC. Through a 2019 Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship I was able to examine the archives for visual evidence of Filipinos and Filipino Americans in an attempt to see how an empire chooses to depict its colony [the Philippines being a US colony in the early part of the 20th Century] and what gets saved as the “official” story.

JL So that’s an effort, on your part, to make some intervention into the archives—to literally place your own hand into the archive.

SS Exactly. What’s really been interesting about this work is—here’s where I think there’s another misunderstanding which I don’t really have any control over, but it’s also how people are positioned to think about artwork made by people of color—a lot of people assume this is about me finding or searching for my Filipino heritage, a longing for a better sense of my identity.

But the work is actually about examining and dissecting the white gaze, not about any sense of cultural authenticity or connection. To be honest, I’m a completely whole and fine individual—I don’t feel lost or torn between two cultures!—and I’m really looking at the cruelty and single-mindedness of the American archives. I chose representations of the Philippines and Filipinos because I feel like I can speak to having a relationship to these images.

For instance, I decided not to work with Native American archives because I feel like that work should be done by Native artists. But hands down, if you’re an artist of color, and you make work that appears to have brown bodies in it, the public thinks that it’s all about you searching for yourself.

JL And that’s just due to how prevalent those kinds of narratives are in the media?

SS I think so. I would appreciate that this work be written about in terms of being about the white gaze, and not about Filipino identity. Those are two very different things.

JL Because when it’s framed as Filipino identity, it’s essentializing, whereas to redirect it towards the white gaze pays attention to how that kind of identity got produced in the first place.

SS Exactly. It implicates everybody, as opposed to being marginalized into a segregated ethnic concern, which unfortunately happens a lot to work by artists of color. Too often the broader public sees works by people of color as a niche concern. It reminds me of how an ethnic studies class isn’t given the same space as a general American history class.

JL What is the place of the viewer who is looking at these pictures? Could you be reproducing that white gaze in the viewer who’s looking at these archival images?

SS That’s why many works in the “Native Resolution” exhibition are explicitly about blocking the viewer. There are crumpled images where you can’t see the original ethnographic racist photo. I also physically cover images with my hands and rephotograph the “edited” images. Everything’s about being denied access to a clear form of looking.

JL I also want to ask you about your own upbringing—growing up and working as an artist in the Bay Area. You’ve said elsewhere that growing up in the 1980s, the counterculture in the Bay Area informed a lot of your visual vocabulary as an artist.

SS I went to art school in the early ’90s at the San Francisco Art Institute, which was a really tumultuous time, the so-called “identity politics era,” when artists of color, queer artists, and other folks who hadn’t been part of the art world canon were starting to gain more visible traction and take up representational space.

So of course there was a lot of backlash and controversy around that, with questions coming up around work by artists of color that in the end functioned to marginalize and delegitimize work not deemed “universal” (i.e. legible to, pertaining to, or centering a “neutral” white experience). It forced me to think, in very complicated ways, about how I was dealing with representation in my work.

There were real fights—there was a lot at stake. I went to school in a predominantly white art school system, in which it was tricky to make work that you felt people could enter, while maintaining integrity in what you wanted to say and critique.

“Too often the broader public sees works by people of color as a niche concern. It reminds me of how an ethnic studies class isn’t given the same space as a general American history class.”

JL What kind of influence did that educational experience have on how you thought about how to personally navigate that question?

SS: It actually inspired me to go into teaching. When you face those issues as a young artist, you think a lot about how you could change that dynamic and dialogue for others. I try to be a conduit for students to have these conversations. If I had political motivations for why I’m a professor now, it’s because I want to make sure that students don’t encounter the same resistances that I did.

I like to think of my work as bilingual or trilingual, which is kind of like code-switching—the work says different things depending on what community it’s approached by. But I don’t try to bury my politics either—it’s a delicate balance. There are just so many assumptions about the type of art that artists of color do, and so I’m very conscious of being pinned down.

If you look at my body of work over the years, I try to shake it up all the time, shifting shapes and mediums and tactics. I’m trying to be as complicated as possible, and maybe even sometimes confusing. I want that to reflect when someone thinks, “what does an Asian-American artist make?” In no way am I trying to erase my position or heritage, but I also refuse to have it conscripted into a typecast role.

JL I want to ask you about our current moment in relation to that. I’m especially curious to hear from you, given your artistic career, about what you believe are ways that people who are Asian-American—but really anyone—can think about reshaping historical and dominant narratives and images of portraying certain kinds of people, when those portrayals have led to violence.

SS That’s a tough one, right? We’re talking about going up against an incredibly long-running and systemic infrastructure of white supremacy. We’re asking groups of people who find themselves at the sharp end of the stick, the other end of the gun, to keep finding ways to prove their humanity.

It’s a predicament that’s inherently unfair. So I guess I can only speak from what I’m doing. For years, I’ve been looking at American archives to think harder about the roots of why we are where we are today, and why certain things keep recurring. All this violence was always there, like a shadow in the background and also in the foreground. This isn’t really a direct answer to your question, except to say that we can’t figure out how we got here or what’s next until we keep looking back to examine how we were not—and are not—represented.

Our histories as Asian-Americans are documented in incomplete ways. The language, the captions of photos in the archive, the news clippings—everything—they’re told from the perspectives of non-Asian-Americans and become the foundation for how things carry forward. But to your question, the path to what can be done is not clear.

JL Right. But part of it, you’re saying, is to understand better what the magnitude of the problem is. To not walk around dazed and confused, as if this is a revelation that this is happening.

SS Exactly. There are deeply racist views that the United States has been invested in for a long time, like labeling who’s a foreigner, a potential criminal, a dirty immigrant, who carries a virus—all these things. There’s a lot we’re up against. But the clearer we are about why or how we got here, the more evidence there is, it becomes harder for people to deny it.

JL One last question. So much of your art is really funny; there’s a lot of humor in it. And with each thing that’s funny, it’s funny in this really perverse way, and it’s not at all detracting from the seriousness of what you’re trying to address. How does humor factor into your art?

SS It’s part of my desire to be a little disarming about some of these topics. Again, different projects demand different things. In some projects, I’m fine with being really strongly positioned and clear. In other cases, I find that either humor, or a kind of absurdity, is wrapped into it.

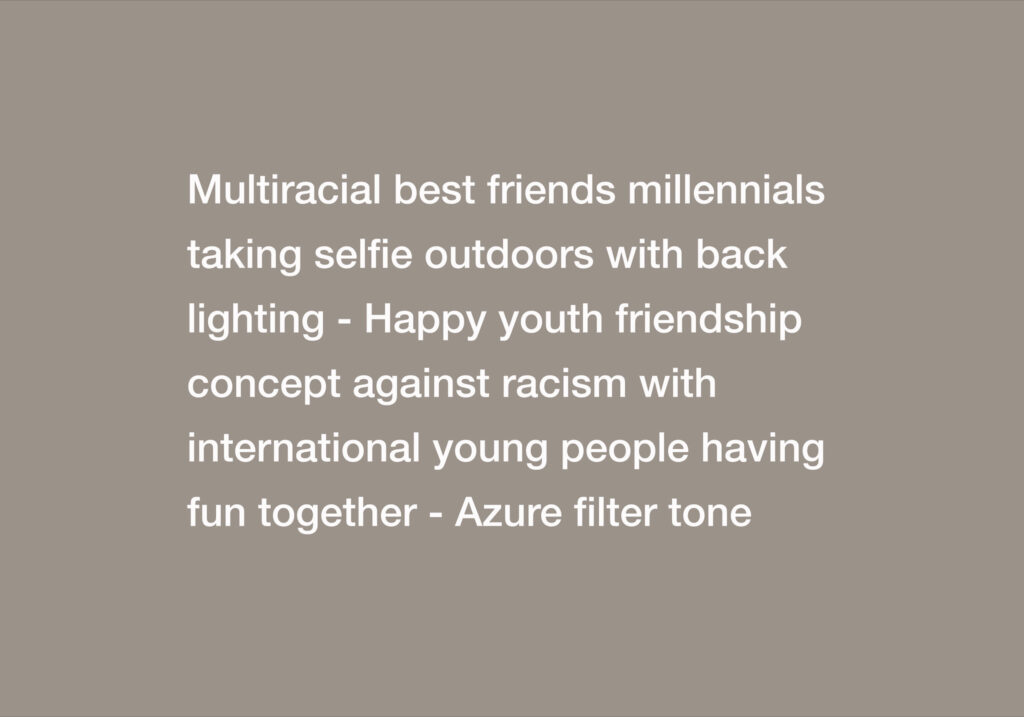

There’s a project I did earlier called Diversity Pictures, where I was looking at captions for stock photography on images of diversity, and then presented them verbatim. The text describing these diverse gatherings and people are ridiculous—they just sound absurd. When you think about it, the people writing these captions are usually white male photographers trying to describe what they see as quickly as possible.

As a person of color reading these, I’m like, “Oh my God! This is what we look like to them.” There’s a cruel absurdity to racism and I think it’s possible to draw attention to how insane its logic structure is. It’s a delicate balance though; you don’t want to do a disservice to an intense and real oppressive force. But if you take a step back and really look at how constructed and elaborate the structure of white supremacy is, it’s horribly, lethally absurd.